Leverage Point #3: The power to add, change, evolve, or self-organize system structure

Research is hard!

I know – to any current and former graduate students out there, this statement is a no-brainer. But to someone who is embarking on independent, full-time research for the first time, it is quite the shock.

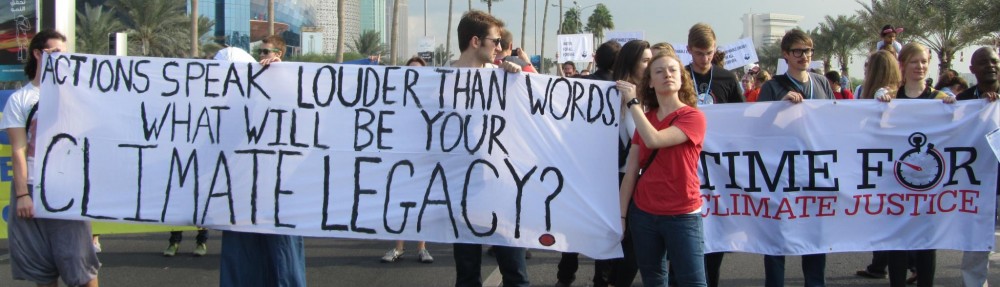

I spent almost two years putting together a proposal for my Senior Fellowship. I agonized over choosing the right topic (not broad enough to be considered vague, not narrow enough to be considered not socially relevant). I knew what I wanted to study, and what kind of research I wanted to pursue. I knew that I wanted to empower young people and marginalized, frontline communities. I knew that I wanted my research to benefit community organizers in their pursuit of climate justice.

I also knew what kind of research I didn’t want to do – I didn’t want my research to be exploitative. I didn’t want to extract data from Northern communities. I wanted my research to engage them. I wanted my research to be useful to them – I wanted their input.

This is so much harder in practice than in theory (surprise!).

Having this self-awareness going into my research made it all the more discouraging when I realized that – despite my good intentions, despite my own personal critiques of research – I was not practicing what I preached about justice-based action research.

As I’ve gone through the past seven months (already?!), I am realizing how it is nearly impossible to engage these frontline communities and actively work with them. I have been constantly racing through my work – always pushing deadlines back. I know that this isn’t necessarily my fault – as a first-time researcher, I tend to underestimate how long work will take, and my project, to borrow words from my Committee, is “exceedingly ambitious” – but I am realizing how the pace and requirements of research (permits, reports, logistical and bureaucratic minutiae) make it very hard to truly consult with communities.

This realization hit me when I applied for a research permit in Nunavut. For my Senior Fellowship, I wanted to work with the community of Clyde River, Nunavut because I knew that they were opposing seismic testing for oil and gas drilling off their coast. Clyde River is a tiny hamlet on Baffin Island with a population of around 935 people, the majority of whom are under eighteen years old. As someone who has helped organize youth campaigns against fossil fuel infrastructure in the past, I wanted to offer my time and resources to this community.

In theory, this sounded great (and, I must say, I am still excited about it). But in practice, it has not been possible to actively consult with community members as much as I’d wanted. In fact, I have been so overwhelmed with my other deadlines, attending COP21, and conducting research interviews that I wasn’t able to connect with any Clyde River community members until late January.

I know that my self-awareness places me already a step ahead of many other research projects, but I am still disappointed that I only began consulting with this community as of late.

However, I also had an “a-ha!” moment: I realized that – just as much as I am studying how the structure of policymaking inhibits progress – the structure of academic research inhibits active community consultation as well. (It was quite meta.)

The structures of systems – big Leverage Points according to Dana Meadows – are powerful because they often affect us without our awareness of them. We are told that the current structure of academic research – the peer-reviewed process, tenure-track, etc. – is simply the way things are. I’m not saying that the tenure process is bad, but I am saying that we need to recognize that the goals of current research – to produce as many peer-reviewed journal articles as possible – doesn’t incentivize community consultation beyond what is required of us to receive our research permits. If we are always overwhelmed by other research obligations, and community engagement throughout each stage of the process isn’t prioritized, the latter will inevitably fall by the wayside.

The good news is that, once we are conscious of this structure, we can go about changing it. I know that I won’t be perfect when it comes to engaging the communities I am working with on this project, but I am going to constantly strive to get as close as I possibly can.