All of the research at the Webster Lab focuses on some aspect of responsive governance, but this project provides detailed and holistic historical documentation of the process of responsive governance. Here, we uses process tracing—or detailed analysis of causal linkages between events over time—to better understand feedbacks between resource depletion, economic behavior, and political action at domestic and international levels. Most of the research for this project has focused on fisheries, as shown by her most recent book, Beyond the Tragedy in Global Fisheries. However, Dr. Webster is currently expanding the project to include water quality, coral bleaching, fossil fuels, and mineral resources. There are three key findings from this project to date: the profit disconnect, the power disconnect, and the management treadmill. Profit and power disconnects disrupt problem signals and delay switching from ineffective to effective governance cycles as shown in Figure H.1. These will be discussed in greater detail below and are the focus of Dr. Webster’s latest project on Global Connections. The management treadmill occurs as systems cycle back and forth between the ineffective and effective response. This can occur endogenously, as rebuilding reduces economic costs and thereby diminishes political will to maintain management (the crisis rebound effect or CRE), or exogenously as factors like economic growth and globalization increase demand, magnifying incentives to overexploit resources and generate excessive amounts of pollution. The latter can be thought of as growth cycle treadmills, and we can expect that the severity and intensity of crises will increase over time as long as exogenous forces persist.

All of the research at the Webster Lab focuses on some aspect of responsive governance, but this project provides detailed and holistic historical documentation of the process of responsive governance. Here, we uses process tracing—or detailed analysis of causal linkages between events over time—to better understand feedbacks between resource depletion, economic behavior, and political action at domestic and international levels. Most of the research for this project has focused on fisheries, as shown by her most recent book, Beyond the Tragedy in Global Fisheries. However, Dr. Webster is currently expanding the project to include water quality, coral bleaching, fossil fuels, and mineral resources. There are three key findings from this project to date: the profit disconnect, the power disconnect, and the management treadmill. Profit and power disconnects disrupt problem signals and delay switching from ineffective to effective governance cycles as shown in Figure H.1. These will be discussed in greater detail below and are the focus of Dr. Webster’s latest project on Global Connections. The management treadmill occurs as systems cycle back and forth between the ineffective and effective response. This can occur endogenously, as rebuilding reduces economic costs and thereby diminishes political will to maintain management (the crisis rebound effect or CRE), or exogenously as factors like economic growth and globalization increase demand, magnifying incentives to overexploit resources and generate excessive amounts of pollution. The latter can be thought of as growth cycle treadmills, and we can expect that the severity and intensity of crises will increase over time as long as exogenous forces persist.

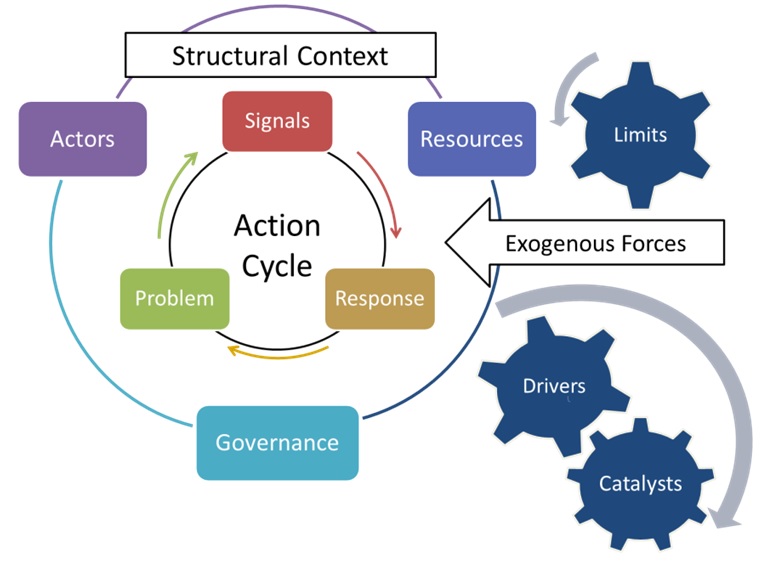

To study the process of responsive governance, Dr. Webster developed the Action Cycle/Structural Context (AC/SC) framework, which she then used to explore the evolution of global fisheries governance in her second book, Beyond the Tragedy in Global Fisheries. As shown in Figure RGP.1 below, the AC/SC framework equates agency with problem solving through an action cycle. Actors choose how to respond to signals they receive about some underlying problem, such as an economic recession, a terrorist threat, or the overexploitation of a stock of fish. The nature of both the individual and aggregate response depends heavily on the structural context in which the decision(s) take place. Over time, however, responses in the action cycle can alter the structural context and thereby affect the behavior of the system as a whole. Figure RGP.1 illustrates these points by embedding the action cycle in the structural context, indicating that action is constrained by the structural context but that the context is itself created by the compounding of actions over time. Exogenous forces also drive, catalyze, or limit the action cycle, and they may operate at different “speeds” than the action cycle itself, as per the panarchy concepts put forth by contributors to Gunderson and Holling, eds. (2002) and further advanced by various authors including Liu et al. (2007), who systematically investigate cyclical and spatial characteristics of coupled human and natural systems.

The AC/SC framework can be used as a deductive or inductive tool. It can guide descriptive analysis in an iterative process that starts with the definition of the core problem(s) and identification of the time period covered by the analysis. Inductively, the AC/SC framework can also be used to formulate testable hypotheses regarding responsive behaviors. These can be aimed at specific levels of analysis or the working of the system as a whole. In either case, one key area of study is the potential for disconnects between problems, singals, and responses. Webster (2015, in press) identifies two key gaps in many environmental arenas: the profit disconnect and the power disconnect. A profit disconnect occurs whenever the equilibrium level of production is higher than the sustainable level of production. This can be caused by a tragedy of the commons, negative externalities, or various other factors that are already well-understood in the literature. However, it is important to recognize that the profit disconnect changes over time and that economic responses to problem signals, such as investment in more efficient technologies, actually widen the profit disconnect and can delay response to environmental problems. The power disconnect in contrast occurs when those who have political power are insulated from economic costs or other key problem signals. This also delays response because those who experience costs have little power to shape governance. There is also a reinforcing feedback loop between the profit disconnect and the power disconnect, which can cause both to increase substantially and severely delay response.

Figure RGP.2 shows how the AC/SC framework can be used to derive testable hypothesis. It focuses on power/profit dynamics in fisheries where commercial fishers are the only powerful interest groups. It outlines expected responses given the combined power/profit disconnect (columns) and distribution of influence among groups of fishers (rows). Rows are further divided into response to conflict signals (top) and response to profit signals (bottom). In general, conflict signals are expected to occur earlier than profit signals and so conflict responses can be expected to precede profit responses, although token conservation measures that are not likely to have much effect on the stock or the fishery may adopted fairly early.

All else equal, when both the profit disconnect and the power disconnect are narrow and influence is uniformly distributed (box 1, upper left), the primary conflict response is collective action and we can expect relatively early conservation response to bioeconomic problem signals. Alternatively, when the profit/power disconnects are wide and power is distributed uniformly among groups of fishers (box 2, upper right), prolonged conflict is likely because bioeconomic signals are delayed and no groups are able to exclude others. Interestingly, conservation-oriented response is also likely to be delayed when the profit/power disconnects are narrow and distribution of power is asymmetrical (box 3, lower left) but for different reasons. Here, less powerful groups of fishers will be excluded fairly early in the action cycle because there are strong bioeconomic problem signals but this will dampen demand for conservation measures. Lastly, when the power/profit disconnects are wide and influence is distributed asymmetrically (box 4, lower right) prolonged conflict and severely delayed management response is expected. In such cases there are usually strong reinforcing feedbacks between profit and power that constantly increase the profitability and political power of capital-rich members of the fishing industry while further marginalizing less wealthy and more vulnerable fishers.

In addition to the ideal-types shown in Figure RGP.2, the AC/SC framework points out two other sets of factors that can affect the timing of governance response in fisheries. First, any component in the structural context that increases the expedience of relatively effective measures can improve the speed of conservation response and vice versa . Second, any factors that alter either the profit disconnect or the power disconnect can switch a system from one category to another and thereby alter response. Endogenously, entrepreneurial behavior by fishers and others in the fishing industry tends to reduce costs of production, expand sources of revenue to multiple stocks or fishing grounds, and increase market demand for fish products. There are also several exogenous drivers that can shift a system from one category to another, such as population growth, economic development, and globalization. In a recent paper, Webster (2015) shows how these hypotheses can be tested using detailed process tracing. Quantitative analysis is also feasible but only when long time series of key variables like the profit disconnect are available. This is not possible in most fisheries but may be more likely in other issue areas where reporting requirements are higher.

References

Gunderson, Lance H, and eds. CS Holling. 2002. Panarchy: Understanding Transformations in Human and Natural Systems. Washington: Island Press.

Liu, Jianguo, Thomas Dietz, Stephen R Carpenter, Carl Folke, Marina Alberti, Charles L Redman, Stephen H Schneider, et al. 2007. “Coupled Human and Natural Systems.” Ambio 36 (8) (December): 639–49. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18240679.

Webster, D.G. in press. Beyond the Tragedy in Global Fisheries. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Webster, D.G. 2015. The Action Cycle/Structural Context Framework: A Fisheries Application. Ecology and Society, 20 (1): 33p.