Carolingian Miniscule owes its fame to Charlemagne, though not its actual creation, it was around long before Charlemagne made it the norm in his empire. Crowned Holy Roman Emperor in 800 A.D. by Pope Leo III, his reign only lasted until 814, Charlemagne was able to bring a large amount of change to Europe and bring back an intellectual populace that had not been known since before the splitting of the Roman Empire into East and West. With education reforms that Charlemagne put in place, the stage was set for a simple, easy to read script meant for the lay person to take over from the many evolved cursive forms used in very formal and courtly documents.

This document will overview the history of the Caroline script as an object of an evolving culture which received special attention in the 9th c. and ruled the majority of Europe’s written text from France to Germany until the 12th c. when the last remnants of this script fade from even the sparing use that they were already reduced to. The specifics of exemplar letters of this script will also be explored and explained for the purpose of being able to identify this script from amidst other medieval manuscripts. For how to actually reproduce the letters, see the contribution by Scott Chapin elsewhere on the site. As well as ending with a brief overview on why people actually care about the letter forms changing and what it means

For clarity purposes for anyone who has not spent much time studying paleography, it will be helpful to have a few specific terms clearly defined for the context of manuscripts: Miniscule: General term for alphabets that are very stylistically similar, but variance in detail construction[1]. script: collection of letters composing the alphabet used for that particular era. Ligature: short-hand way of writing combinations of letters without lifting the pen, think cursive, but only used for particular letter combinations. Ascenders and descenders: in miniscule scripts, parts of a letter that stand up above the rest of the letter, or drop lower i.e. p, h, b, f, s with the tall form. Any others will be explained in context, these are simply used very often and it is useful to know them from the outset.

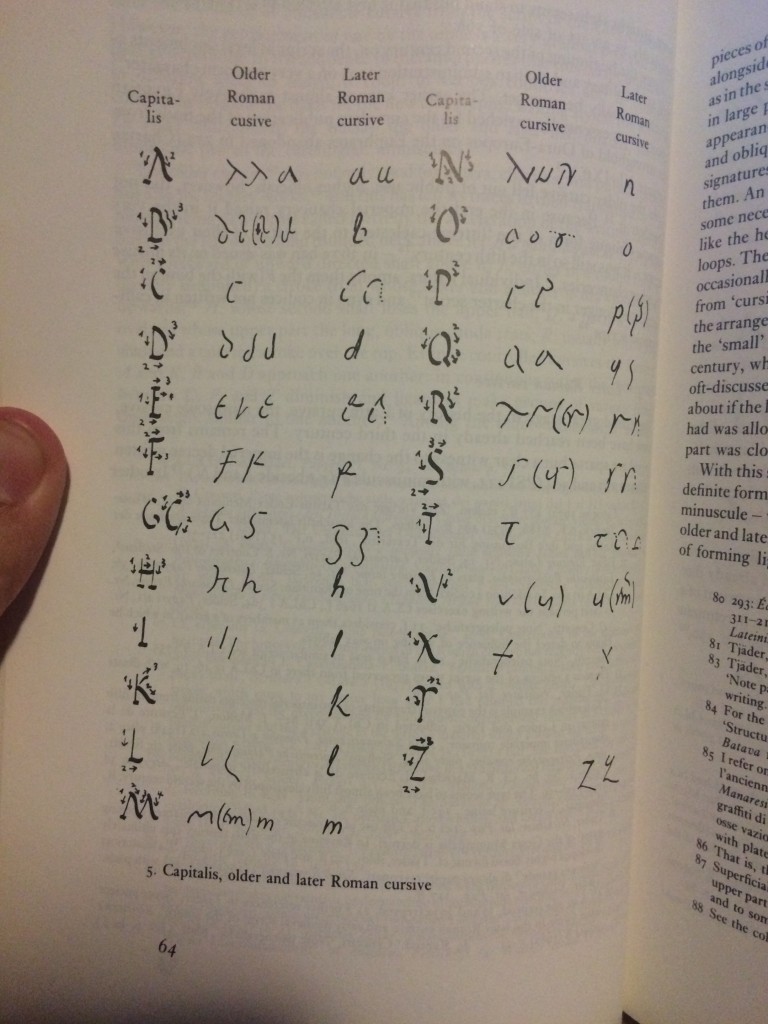

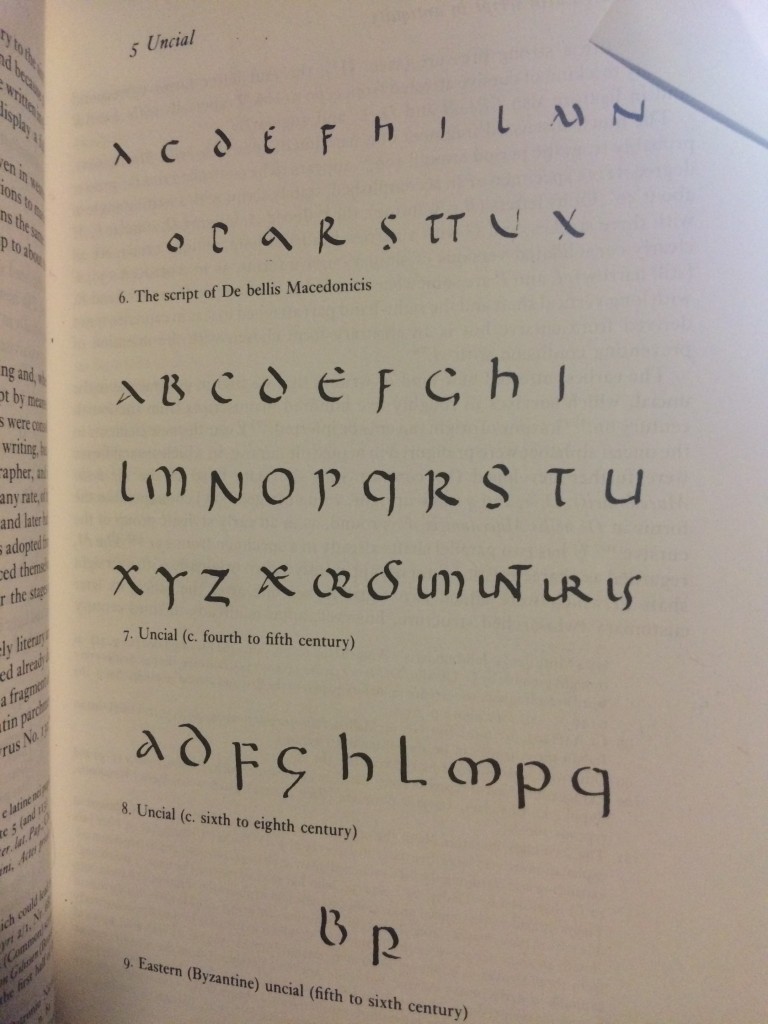

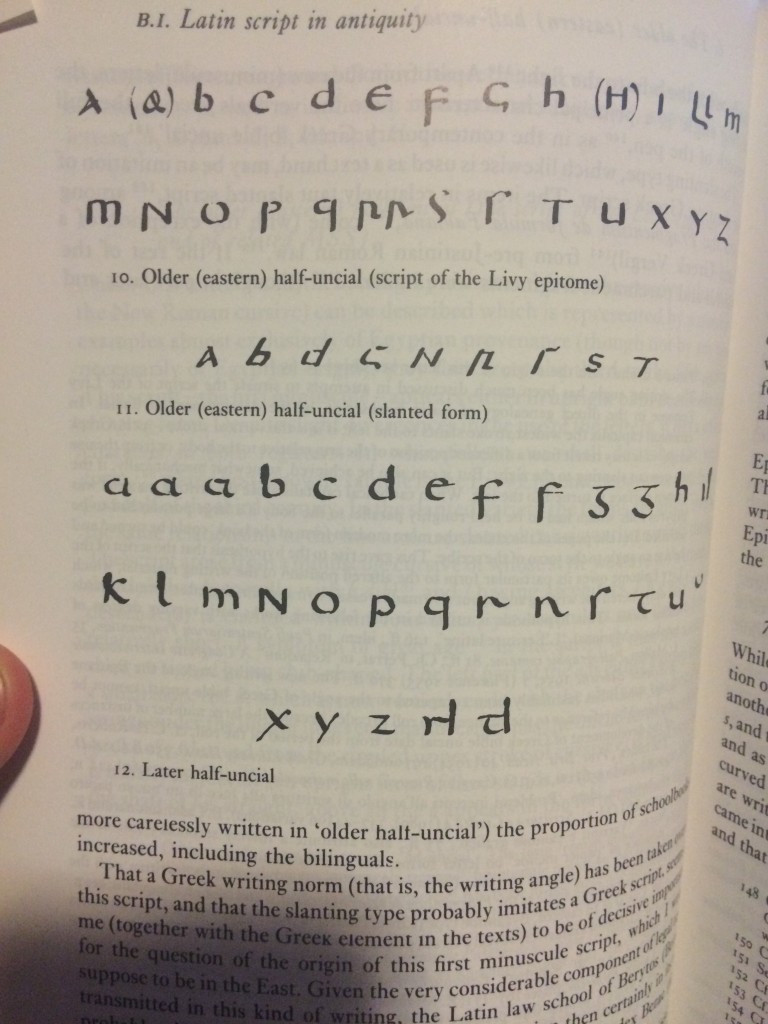

The letterforms that came to be known as Caroline miniscule originally evolved from earlier uses and influences of Roman cursive and half uncial, two scripts with forms that were quick to write, relatively easy to identify, and quite rounded in shape, though some influence of Byzantine letters are also found, particularly in Ravenna around 7th-8th centuries[2]. These attributes would continue to define Caroline miniscule and keep it distinct from the plethora of other scripts which came and went in the following centuries. Merovingian scripts with slender, narrow letters very much continuing the late Roman cursive forms, are also particularly present in influencing the Carolingian script, especially in France and Northern Italy. Many miniscule scripts emerge, beginning around 760 A.D. with Alemannic miniscule[3], from the dying embers of Uncial and half Uncial, and cursive scripts very closely related to both old and new Roman cursive. Alemannic miniscule mediated French and Italian tendencies, while establishing its own distinctive forms to differentiate it from the coming Caroline miniscule.

Carolingian miniscule, indeed miniscule scripts in general were common by the time Charlemagne came to power, and it is now that the King began to praise the balance and order that the miniscule scripts provided, over the less readable, more difficult to write cursives which were being used throughout France and Lombardy. However, even though miniscule scripts existed, there were many regional variants, many ligatures used, which made it complicated to institute a unified script immediately as many places practiced the unified script Charlemagne wanted implemented, however still used their regional script for much of the work[4]. Carolingian miniscule finally became the predominant script in most scriptoria around 820 A.D., six years after Charlemagne’s death.

While he was alive, Charlemagne went to great lengths to bring back the glory of the Roman empire, now reborn as the Holy Roman Empire. The Roman empire’s power, prestiege, and success came from the organization of huge swaths of land all working towards a common goal, or at least of one mind should a goal or need present itself, and indeed creating a lasting system of power requires many people to be working together from very long distances, which requires more literacy than it does today; Europe had lost most of its literacy after the fall of Rome in the 5th century. Charlemagne tried to combat this by instituting universal education reforms which included a standardization of script to be used throughout the empire, and a mission to copy as many manuscripts as possible to bring reading and a learned populace back to Europe, as much as he wanted to raise the moral standing of the empire. With this drive to educate the people, Charlemagne not only pushed to standardize the liturgical tradition and canon law, but he also had copies made of as many secular, ancient texts that had survived to that point, such was his determination to rid ignorance from his land.

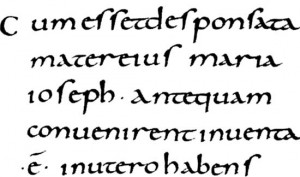

The most distinctive letters in this script are the a and s. The a has several variants, but its construction is basically to of the letter c put directly next to each other, sometimes with a closed loop where the horns of the first c meet the second, sometimes with the top horn is disconnected, early on it still looks like the uncial version with a belly on the left of a short, slightly curved line slanting from left to right. The closed form of the a could end up looking like a lowercase Greek alpha, depending on how much curve the scribe put into the letters. The s is the furthest from our current script, and oddly changed from a similar form as we have today. The Carolingian s, known as the “tall s” is exactly that, somewhere between a lowercase l with a modern shoulder from a lowercase r, and came about due to commentary, and the need for better space management on the page[5]. These two letters are the easiest way to identify a manuscript as being from the Carolingian era, however each letter has its own small details that mark it as being Carolingian, particularly the t. The construction of many Carolingian letters include the c and the t is no exception, being a c with a horizontal crossbar at the top, this is also a very easy letter to pick out.

When the Insular script, which started in Ireland, died out in Germany and Britain in the late 9th century, Caroline script filled the void as the bookhand, and used for charter writing for much of Europe, however by the end of the 9th c. in France and Germany, the Caroline script began to lose some of the character it had, and was being written with unsure hands. Caroloine miniscule finally makes it England in the 10th century where runic symbols were also kept, along with there being a strong Norman presence and eventually influence. The 11th century sees more changes and unsure execution of scripts in France and Germany, however a differentiation of ae and oe sounds while writing the e caudata, and a weak punctuation mark are added. These changes, while useful for a more organic, natural representation of writing, still meant that the Carolingian miniscule itself was falling out of use, slowly being altered and adapted until it was no longer the original letter forms. During this time (beginning of 10th c.), up until about the 12th century, Gothic script is developing in Germany and begins to be used alongside Caroline script very early, and eventually takes over as the dominant script, while similar distance to Caroline scripts are happening in France. Southern Italy mind you has been using Beneventan script for nearly as long as Caroline miniscule was being developed, and was relatively unchanged until also around the 12th century when letters become more slanted and round bodies are very pronounced (known as “Farfa” script, or “miniscola romana”[6]). It is important to note that much of the medieval illumination was done during the Carolingian era, however that is not the topic at hand here so that’s all that will be said on it.

To conclude, the regularity and lack of many ligatures and overall structure of the Roman cursives which influenced the creation of miniscule scripts gave them a leg up on the cursive scripts which had held dominance in the scribal world until Charlemagne placed educational reforms and standardized both the script to be easy to read for the lay people, and the practice of copying ancient texts as well as liturgical and canon manuscripts and amassing large numbers of documents. Without these reforms and practices, many of the ancient texts which make up the backbone of our historical knowledge would have been forever lost; for this reason Caroline miniscule is incredibly important to the entire world because without it, we may not have the texts that we do now.

Notes

[1] Bischoff, Bernhard. Latin Paleography, p.107

[2]Bischoff p.101

[3] Bischoff p.107

[4] Bischoff p.114

[5] Bischoff p.121

[6] Bischoff p.125

Works Consulted

Bischoff, Bernhard. Latin Paleography. Cambridge University Press, 1990

Clemens, Raymond & Graham, Timothy. Introduction to Manuscript Studies. Cornell University Press, 2007

Various class lectures from this course with Professor Thomas Hendrickson

www.britannica.com

Pingback: Illuminated Manuscripts – Repetition and Contrast

Pingback: อักษรสไตล์ - Carolingian minuscule -

I love this page, but I am wondering about some of its mistakes in English. The most annoying error, given the subject of the page, is that the misspelling “miniscule” (instead of the correct “minuscule”) appears throughout this page: literally every time the word is used.

Would you be willing to correct this repeated error, and are you open to being informed about the page’s other (and much smaller) lapses from standard written English?

Pingback: Were the Middle Ages that Dark as some historians often describe the period? - World History Edu

Pingback: The Cultural Revival of a Continent – European Art News

Pingback: 7 Ancient Western Calligraphy Fonts That Will Enhance Your Presentation - muqahhar

Pingback: The cultural renewal of a continent – panagia.site