Leverage Point #5: The rules of the system (such as incentives, punishment, constraints)

Leverage Point #4: The power to add, change, evolve, or self-organize system structure

Leverage Point #3: The goals of the system

I have been to nine UN conferences relating to climate change. COP21 is my fourth such Conference of the Parties (the annual jargon-filled UN Framework Convention on Climate Change conference we have all come to know and love). Every year, I feel more and more like I both know this process inside out, and more and more like I am completely unprepared to be here. It is a tough two weeks (or more, if talks go into overtime) – I feel like I will never be able to fully grasp what is going on here.

The realization that I will never be prepared for COP is quite concerning: I am a student with quite extensive research experience with climate change. I am a COP veteran, in some sense. I spend months before COP planning, reading and re-reading draft negotiation texts. I am here as part of a team of incredibly brilliant young people. If I am not capable of getting a handle on these negotiations, how can we expect negotiators from poor and developing countries – country delegations sometimes with only two full delegates at the conference – to be able to have a voice here?

Many of Dana Meadows’ Leverage Points relate to system structure (Leverage Points #6: the structure of information flow; #5: the rules of the system; and #4: the power to add, change, evolve, or self-organize system structure). Within the UNFCCC, I am interested in how the structure of the conference itself – beyond the usual “bad actors” countries – contribute to this process’s failure. Here are some components of flawed system structure I have noticed so far (more to come!):

1. Inaccessibility.

The UNFCCC functions on a ridiculous amount of jargon. There are hundreds of acronyms that are used – it is absolutely absurd. Some NGOs try to help lighten this load by offering “acronym dictionaries” and guides to the negotiations – but this jargon makes it essentially impossible for an engaged citizen to be a part of this process. While I recognize that complexity is necessary for a multilateral process of this scale, the extent to which jargon permeates – I would even argue, encouraged – within COP is excessive. I’ve attached a photo of just one example – for those of you who didn’t already know, MECGCCRPRNF stands for the Ministère de l’Environnement Chargé de la Gestion des Changements Climatiques, du Reboisement et de la Protection des Ressources Naturelles et Forestières (the Republic of Benin’s environmental agency):

2. Stifling of civil society voices.

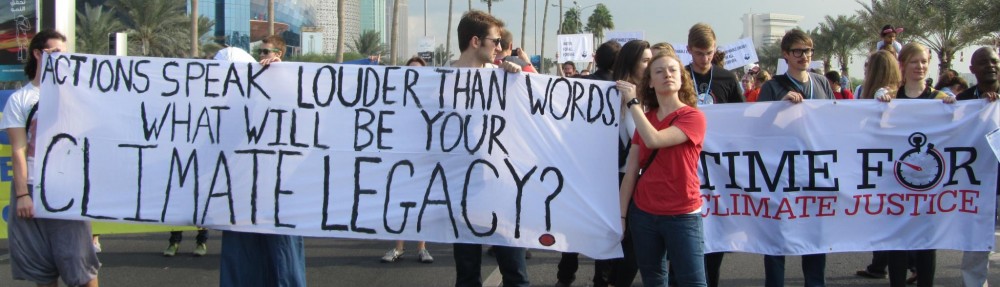

As members of civil society, we are rarely given the opportunity to speak within the UNFCCC space. We are told that we are capable of voicing dissent or frustration, but only within certain rules (we can only gather in designated areas; we must apply for permission to use said areas at least 24 hours in advance; we may not be overly disruptive; we may not target specific countries or government leaders). This stifling is an example of the third realm of power – wherein a group isn’t directly conscious that power is being exerted upon them. We are told that the

The Fossil of the Day awards, presented by the Climate Action Network, are theatrical award ceremonies that honour the “worst of the worst” of the UN negotiations.

3. Exacerbating existing power structures.

Countries have no limits to the delegations they can bring to COP – so large countries like the US can bring a team of hundreds of people here, while some small island nations can only bring a handful. These disparities in both financial and human resources are significant when realizing that there are often multiple different negotiation sessions happening around the clock at the UNFCCC – so much so that it would be impossible for a small country delegation to effectively represent itself. The UNFCCC process thus reinforces the processes that caused this problem in the first place, with developed countries being overrepresented, and developing countries being overworked.

4. Marginalization of youth.

Where do I even begin? Youth are tokenized and, for all intents and purposes, left out of this process. We are told we can take “selfies” with our Prime Minister, but aren’t allowed to have a formal meeting with him. We are told to Tweet, to use social media, but aren’t given a seat at the table. The system of delegating youth to “observer” roles perpetuates our inability to speak for our generation, and for future generations.

very nice… i really like your blog. Very useful informations. you have a decent article for we read