(This media piece was published in The Dartmouth.)

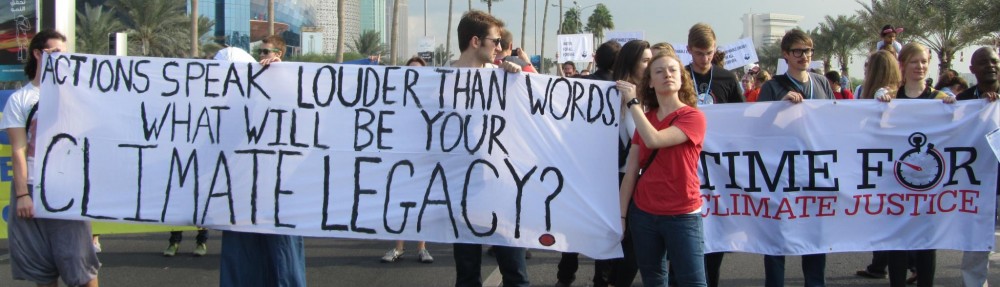

Our voices matter.

The gravity of this realization shouldn’t be lost on us: we are powerful as young people. We can shape this world into whatever vision we carry for it.

It’s sometimes hard, though, to embody this statement. How can our voices matter in a world that is meant to silence them? How can we speak up about issues that matter to our generation if we are told these very issues are too large, too complex, too systemic to handle?

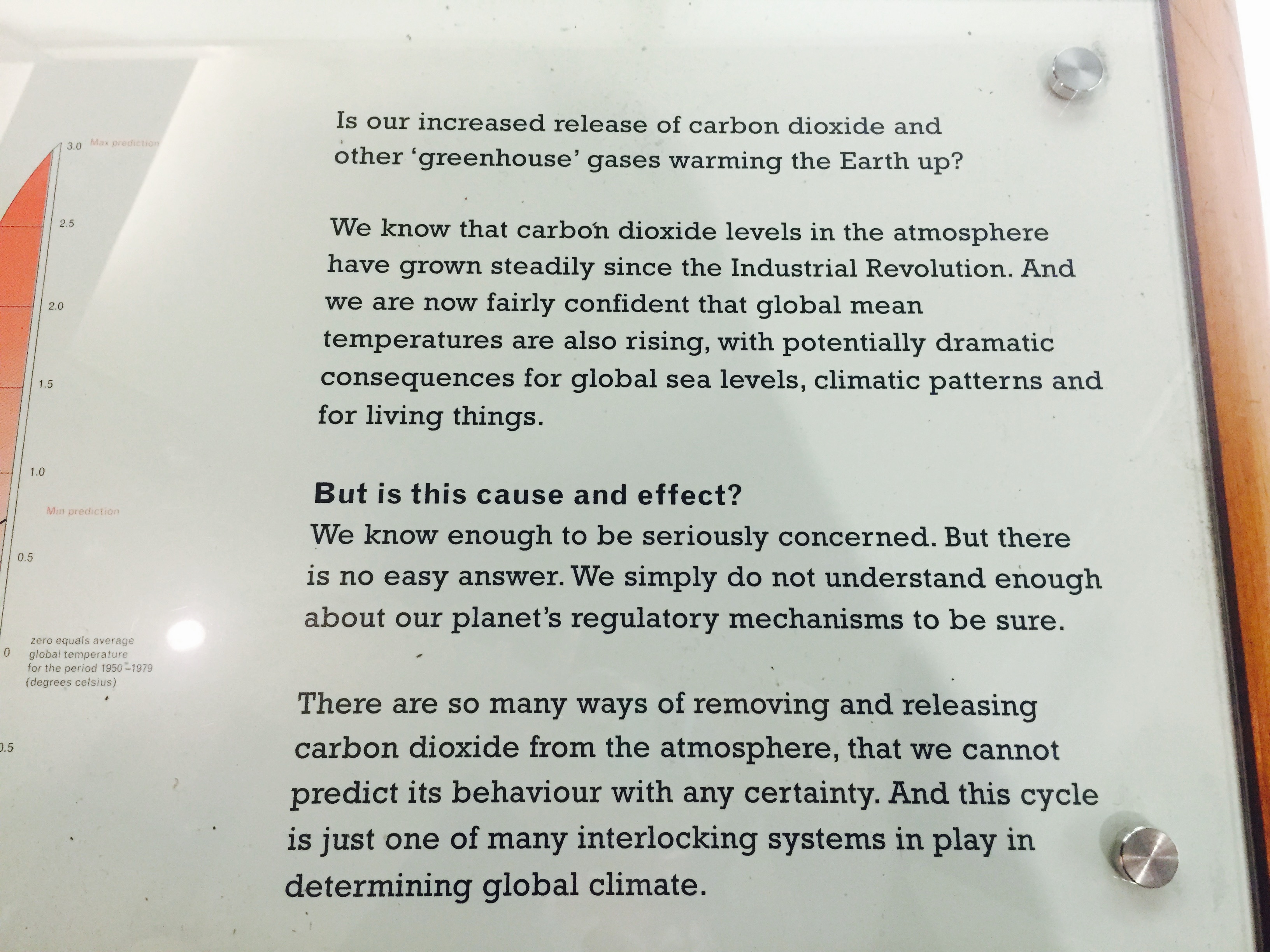

I think about climate change all the time. Those who know me on campus know that this issue has defined my four years at Dartmouth, particularly through my involvement with Divest Dartmouth. I see the ways in which this problem will affect our futures: hundreds of millions forcibly displaced due to sea level rise and natural resource conflict. The rise of vector-borne viruses such as Lyme disease and Zika. We’ll have the resources to adapt in New York City, but Manila will be underwater. Climate change will affect our health, our economy and our society — and it will disproportionately affect communities that are already on the front lines of socioeconomic, racial and gender-based injustices.

The reality of climate change is very insistent. But it is complex and difficult and systemic — how can we solve a problem that is so wicked?

This question has guided my research this year as a senior fellow. I spend my days agonizing over it and have come to realize how much our ability to solve monumental problems is rooted in the power we wield to shift society.

Do young people have power? I have been conducting interviews for my research, and asking my research subjects — scientists, policy makers and activists working on climate change — this question. Of the many insightful answers, one sticks out: “People feel empowered when the responsibility they feel for a problem is equal to the power they have to solve it.”

When it comes to big problems, we as young people oftentimes feel this responsibility most strongly. I know that I myself feel this viscerally: I cannot accept the futures that scientists are predicting for us under unchecked climate change. I recognize the rights of my generation to live in a world that has at least as many opportunities as the one into which the generations before us were born.

What about power?

It isn’t always obvious to see the ways in which power is exerted over us. In particular, we don’t think about how the way certain institutions are structured influences how empowered we feel.

Think about the D-Plan: We’ve come to accept this quarterly structure as a given, despite the fact that it has only been implemented for about forty years. And yet, the D-Plan affects us in ways that we may not always be aware of. For example, most of us realize its impact on our ability to maintain relationships. It’s hard to have a relationship between two people at Dartmouth who might not see each other for the better part of a year.

Why should we care about systems of power? Institutional change is a core part of Dartmouth’s tradition. Our College has been shaped by a rich history of students before us who wanted it to be better — from women who fought for the inclusion of “daughters of Dartmouth” in the alma mater, to students who fought (and are still fighting) for the abolition of the Indian head symbol to students who founded the Dartmouth Outing Club.

When we realize that we not only carry a responsibility to make this world better, but that we are indeed capable of changing it, we become empowered to forge ahead working on problems that may seem too significant to challenge. When we realize we are powerful, we push ourselves to do things that terrify us because we know they are important, and we grow. When we start noticing the structures that disempower us, we can go about changing them to create the world we seek.

Our voices matter.