Should the Hovey Murals have been Removed?

From the editors:

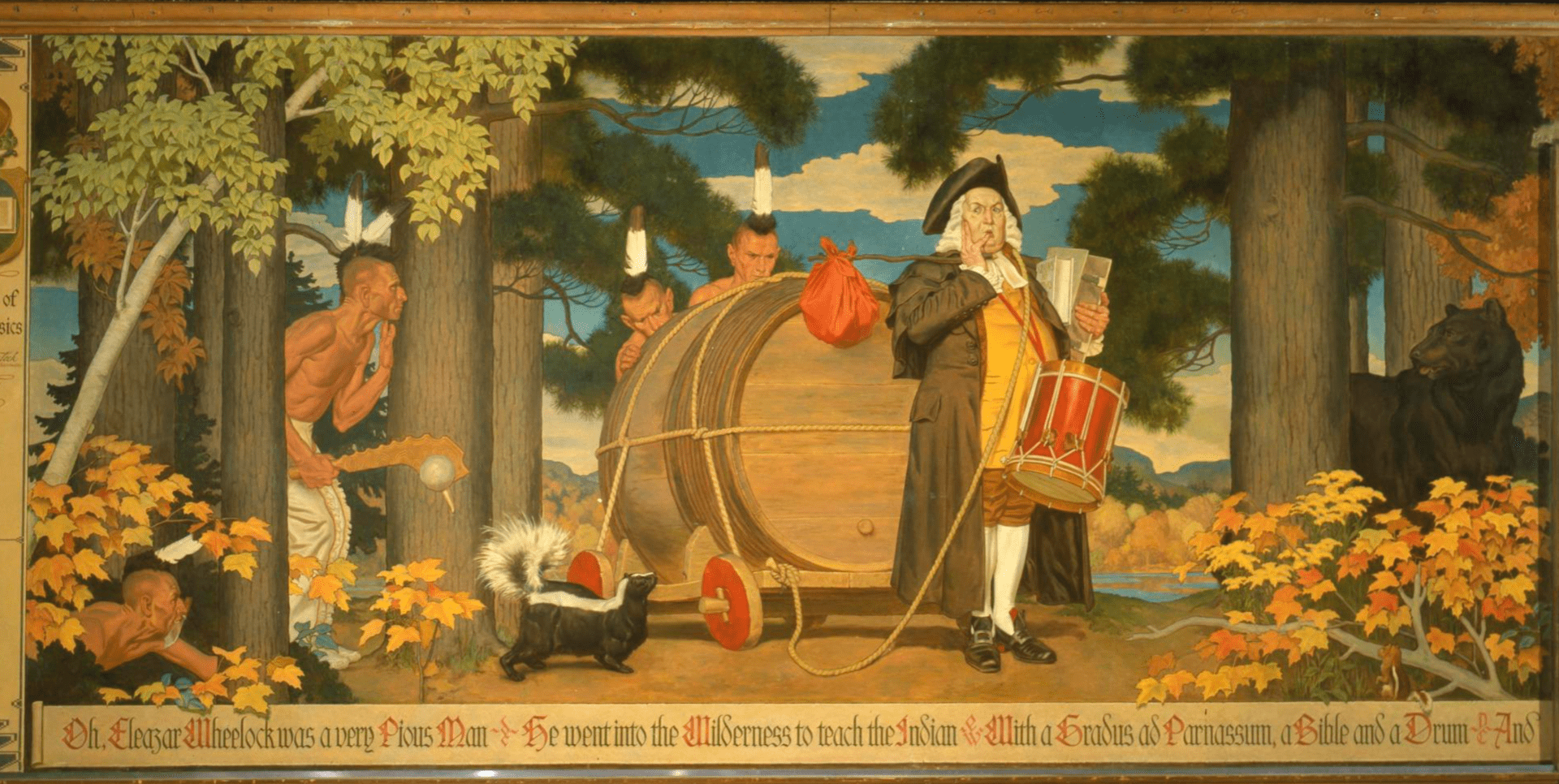

The Hovey Murals are a set of paintings with racist depictions of indigenous peoples that purport to depict Dartmouth’s founding. They used adorned the walls of the basement of the Class of 1953 Commons dining hall, an exclusive dining space for Dartmouth professors and students to eat steak and smoke cigars, until the 1970s when the room was locked to the public

Now, the paintings reside in an off campus Hood Museum art storage facility after Hovey Murals Study Group decided to move them. The public does not have access to the murals, but students and faculty still do if faculty elect to include them in their course material.

Pro

The Hovey Murals painted in the late 1930s after Walter Humphrey’s request for a more “Dartmouth” mural than Orozco’s work have no place on our campus nor in today’s society. President Hanlon’s decision to put them in the Hood museum’s off campus storage is entirely inadequate. The murals depict Native Americans as uncivilized, drunk, and illiterate; Native women are reduced to serving one purpose to Dartmouth and society: sexual objects. This is not only a disgusting representation of Native Americans, but also severely historically inaccurate depiction of how Natives dressed and lived in the early 20th century. There is no plausible reason for keeping the paintings. The Hovey Murals only hold us back from what Dartmouth acts like it cares about.

How can we have discussions on sexual assault and gender equality while holding tight to these paintings and keeping them in the storage of an art museum? The “Moving Dartmouth Forward” initiative loses a lot of credibility when our college maintains disgusting images of our flawed and racist past. The argument that we should keep them as a teaching tool is strange, given they are already well documented and accompanied by a wonderful article by Professor Calloway in Rauner, among others. We need to make a statement that we care about Native Americans and inclusivity in general. We need to make a statement that we care about gender equality and do not stand for sexualized representations of women.

Keeping these murals in an art museum’s storage shows that we value them as works of art. Hanlon stated that the “derogatory images in the Hovey murals convey disturbing messages that are incompatible with Dartmouth’s mission and values.” That statement in no way aligns with his decision for the college to maintain ownership of the murals, implicitly valuing them as works of art deserving of museum storage. Interim provost David Kotz also affirmed that “As an institution of higher education, we recognize the murals’ value as a teaching tool… we also recognize that the murals are deeply insulting to Native Americans and many others in the Dartmouth community.”

What value are we getting in keeping the physical objects? We live in a time when photographic images are just as descriptive as viewing the paintings in person. It is frankly embarrassing that Dartmouth is so oddly attached to the physical objects. It is time that we follow up buzzwords with action and destroy these paintings. It is time we make a statement.

– Anonymous

Con

Do we perpetuate traditions for their own sake or for ours? When we consider phenomena such as the Dartmouth Indian, how do these traditions reflect upon our community and our shared social history? In reality, Dartmouth graduated fewer than two dozen Native students in the first 200 years of the College’s history. The Dartmouth Indian was the only Indian present on this campus for many years. This should silence the argument that it was a symbol or sign of respect for Native peoples, since there were no actual Dartmouth students on campus who could voice their opinions on this type of “respect.”

The Hovey Murals are one of the truest examples of historical feelings towards Native peoples on Dartmouth’s campus. Commissioned by the College in the late 1930s after outcry from alumni directed at the Orozco Murals, the Hovey Murals were called “real Dartmouth murals.”

Walter Beach Humphrey, the artist, based the murals off of an old Dartmouth drinking song depicting 500 gallons of New England rum, drunk Indian men, and sexualized Native women. Eleazar Wheelock stands center, surrounded by barrels of rum, Indian men, and nearly naked Indian women. Though they have been covered for at least a decade and closed off from public view, the murals represent more than a sore spot among the Native community at Dartmouth and many Native alums. Dartmouth’s refusal to take action has left the College in a moral limbo at the cost of Native pride, self-esteem, and self-worth. Dartmouth calls Native students to its campus by parading a strong indigenous community, an incredible NAP and NAS program, and its long Native history. However, when students arrive at the College they are greeted by countless obstacles telling them they do not belong here. Whether in the form of murals, Indian head tattoos, or affirmative action accusations, Native students are constantly reminded that the College which was literally built for them has never been theirs.

The Hovey Murals have been preserved for years under the argument that their preservation attests to Dartmouth’s complicated history with Native peoples. If we really had a dedication to Dartmouth’s Native history, shouldn’t that take the form of dedication to Dartmouth’s current Native students?

Nonetheless, the murals represent an important part of Dartmouth’s past, and ultimately the decision to remove and preserve them was the correct one. To leave them on campus would be to ignore the outcry among indigenous students that has been happening for decades. By removing them and preserving, the College takes an important step in recognizing the wishes of its Native students, those closest to the issue undoubtedly, while also acknowledging the important educational purpose the murals may serve in the future. Dartmouth must remember its past if it is ever to do right by its current students. The murals represent a possible first step in the dedication of Dartmouth to recognizing and reconciling with its Native history, to rededicating itself to its Native students after 50 years.

– Anonymous