The Dux Forest: Socio-Environmental Entanglement in Central Italy

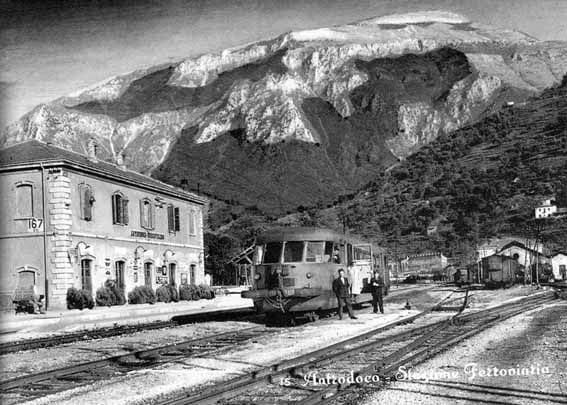

On the slopes of Mount Giano, above the town of Antrodoco in central Italy, lies a fascist forest. In 1938, in homage to then-dictator Benito Mussolini, recruits studying at the nearby Academy of the Forestry Corpsplanted 20,000 black Austrian pines to spell out DUX, the fascist leader’s title in Latin. The planting coincided with the celebrated opening of a major aqueduct commissioned by Mussolini to sustain a growing Rome.

This controversial formation stood intact until August 2017 when a fire–deemed an accident–burned down part of the forest, again altering theecosystem and giving rise to a critical conversation about the meanings and values of manipulated human landscapes.

The debate has ensued about the future of this arboreal monument to Italian fascism, eliciting varied reactions from outsiders: some, mortified that it has survived solong,advocate its total erasure, whileneo-fascist groups have begunplansto restore it.Others have instead arguedthatthe forest ought toremainas both a reminder of Italy’s brutal past—indeedaprime example of the fascist appropriation of landscapes to mark theregime’s domination ofboth the country and its nature—andan inviolable elementof the Antrodoco’shistoryand sense of place.Most notably, however, the fire has generated an opportunity for the local community to engage with the peculiar history of their regional environment—one exploited for its rich natural resources, especially its water,since antiquity—as well as with new narratives that promote both economic progress and cultural development on ecological grounds.

Debatesabout the intersection of landscape history, socio-political narratives,and environmental preservation lie at the core of my work as an environmental humanist. The DUX forest case highlights how a landscape is not onlya spectaclebut also a repository of stories, a concrete three-dimensional shared reality characterized by a series of processes and connectionsthat weave together political institutions, human communities,and the natural environment. Through my study of the forest in an environmental, political,and social context, I aim to analyze the mutual connection of humans and place as well as to reinforce an historical understanding of the complex bond between cultural identity, social awareness, and landscape protection. Ultimately, the forest above Antrodoco embodies what geographer Kenneth Olwig has called “a substantive performing landscape,” i.e.a nexus of community, justice, nature, and environmental equity. As such, it must be both historically contextualized and ecologically preserved to serveas a model for reflecting on the relationships between landscape planning and our current socio-environmental crisis.