This is part 3 of a series I’m writing on how data can inform classroom and online discussions. If you’d like some background on this topic, check out part 1, and if you’d like to see a different way to encounter the discussion data, check out part 2.

Like many instructional design teams, our team at Dartmouth is skilled at solving problems from multiple approaches. We don’t believe in a one-size-fits-all approach to education. Recently, we’ve had a chance to contrast, complement, and balance our approaches to an important educational tool: online discussion boards.

We were spurred by a new app developed by our colleague Jing Qi. It’s for use in the Canvas Learning Management system, the system we use at Dartmouth to help manage the course content for our students and instructors. One of the features of this system is online discussion boards, where students can answer instructor prompts and interact with one another’s ideas. Jing built a custom script that instructors – or the instructional designers, on the instructor’s behalf – can install on the Canvas discussion boards. The script prepares a data file of every student response, its word length, who it was to, and who it was from. The script can then be loaded into a freely available shiny app (also built by Jing) that visualizes the communication connections between the students.

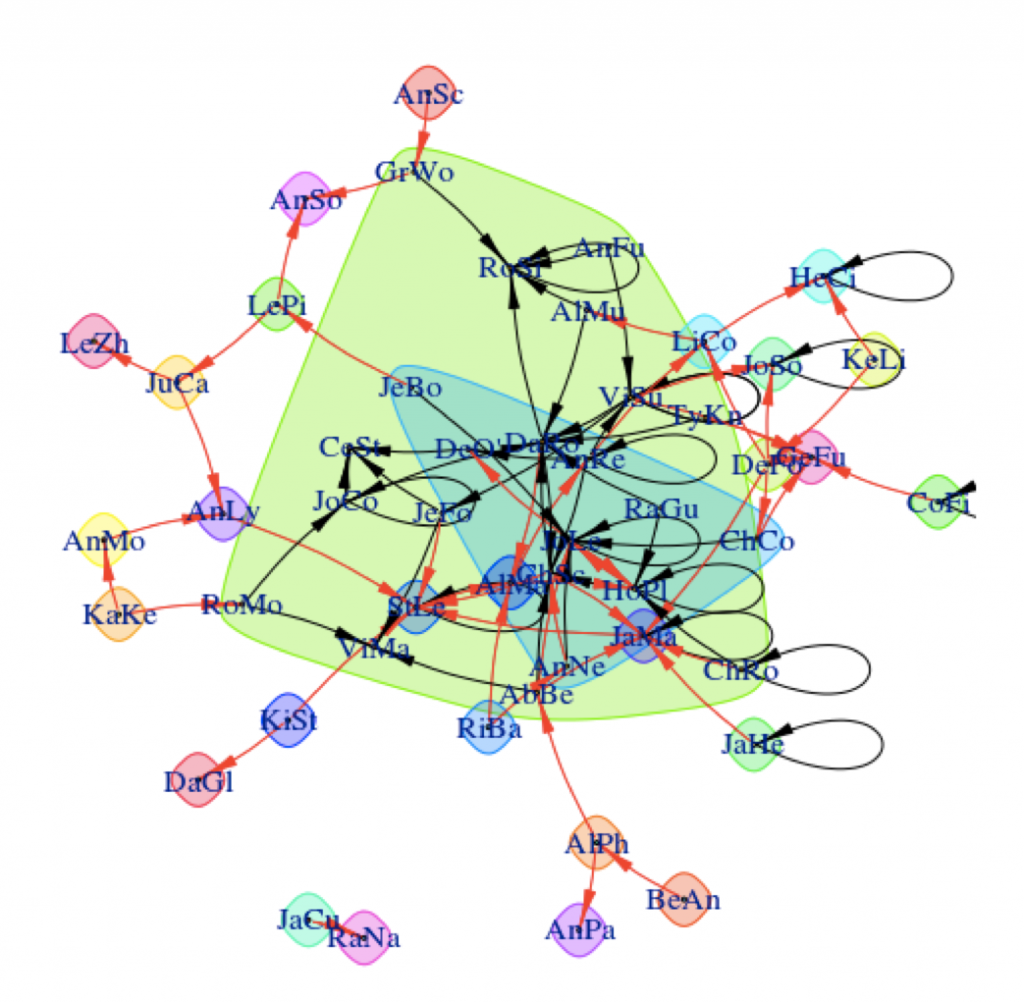

On the surface, the visualizations are fairly easy to interpret. Students who have discussed with one another are linked by arrows, with the head of the arrow pointing in the direction of communication. Strong connections between students are linked by wide lines, and communities of students are surrounded by colored shapes. The visualizations provide a snapshot of what’s happening between the students in the class.

Data visualization from Jing Qi’s shiny app.

Yet…a snapshot is worth a 1,000 words. My colleague Scott Millspaugh and I interpreted the data from these visualizations in different ways, and both methods are useful to instructors for different reasons.

Scott focused on the nodes of the network, which represent individual students. He noticed that some students had stronger connections than others and in part 2 of this series, I shared some of his methods and strategies for assessing student-level data and using this data to improve the structure of online discussions.

My background is in the social sciences, so I couldn’t help but focus on the societies I saw in the visualizations from Jing’s app. I was particularly concerned when I saw some students interacting strongly with one another and some students isolated from the broader class. In the visualization below, you can see what I’m talking about. There are students on the edges of conversations, outside of groups. There’s even two students who look like they’re only talking to each other.

That’s not ideal. Discussion boards are opportunities for student to empower themselves through their writing, reflect on what they’ve learned, build community and identity, and develop their peer-peer learning skills. Discussions boards can be wonderful. But discussions – whether online or in-person – operate best when diverse voices are included. Students on the periphery aren’t sharing their voices or they are having their voices ignored. As educators, we have a responsibility to work with students both inside and outside of groups to ensure that everyone is included.

“Discussions – whether online or in-person – operate best when diverse voices are included.”

Fortunately, the strategies for increasing student engagement with online discussion boards are very similar to those used in classroom discussions. Here’s nine ways to get students talking to one another on online discussion boards.

- Instructor prompts: Direct students to one another’s comments. Example? “Hey Bill and Ted, I’m noticing you solved this problem in two different ways. Are there points of commonality between your approaches?”

- Requiring multiple responses: Consider requiring that students respond to a minimum number of other students before receiving full marks on their assignment.

- Opening the floor: Revisit the discussion and make sure that multiple views or solutions from the students are invited and encourage. Are your questions clearly communicating to students that conversations are valued and expected.

- Asking students to role-play: You could assign particular roles to students like facilitator, peacemaker, Devil’s advocate, summarizer, etc. and ask them to post on the discussion board as if they were speaking from their role. You could also ask students to reimagine a scenario from a different perspective.

- Affinity groups: You could group similar responses together into “themes” and then ask students within each theme to comment on one another’s posts. Or, better yet, have the students group the responses into themes and explained why they grouped them that way. (This is a great activity to bridge in-class and online discussions.)

- Think-pair-share: Ask students to think about what they plan to post on the discussion board, then share that idea with the student sitting next to them. Give a few minutes for students to discuss their responses and help each other, then invite the students to share what they learned on the discussion board.

- Fishbowls: Using anonymized discussions (perhaps discussions from previous iterations of a course), ask students to comment on the quality of responses they see. Do they notice areas where communication succeed or where it needs improvement? This kind of activity often spurs student groups to self-correct themselves and include more voices in their discussions.

- Assigning small groups: One of the problems with discussion boards in larger classes is that students simply can’t respond to everyone, and there’s little chance they’ll get a response back to their own post. Break down those gaps by assigning small groups, where students know who their correspondents are. With discussion data, it’s relatively easy to form these small groups in a way that will ensure more students are included in conversations. An instructor could pick some students for the group from well-established communities in the course and some students from the peripheral voices.

- Jigsaws: If you have existing small groups in your course, it might be time to mix-and-match them so that students hear from new voices. One of my favorite mix-and-match methods is the jigsaw, where a new group is formed from one representative of each of the existing small groups in class. (So if you have 4 groups of 5 people, you would jigsaw to make 5 new groups, each with 4 people, one person from each group). Each of the representatives will bring their former group’s perspective to the newly formed group.

Phew! A long list of strategies for resetting and jump-starting online discussion boards. I hope you found some of them useful. (And if you did, could you let me know? What strategies do you use in your classroom or online discussions, or what strategies do you think are missing from this list?)

This is what I love about data-driven decision-making. It gives me information I need, then opens up a range of appropriate, potential next-steps. It doesn’t hand me the answer, but it gets me thinking in the right direction. Jing’s app took raw data from the Canvas system and processed it into visualizations I could easily understand. I identified something that I, if I were an instructor in this course, might want to change. I could research and adopt strategies that might enact the change I want to see. And when I’m ready, after those strategies have been employed, I can watch the data change over time and see if my strategies are working. Data is a lamp that lights my way.

I hope you found this series useful, and thank you for reading it. I’m hoping to write more on learning analytics and discussion data in the future, and if you’d like to see me address a topic of interest to you, please let me know. Feel free to get in touch. You can comment here or email me at kes.schroer(at)dartmouth.edu.