BLUEBEARD // ORIENTALISM

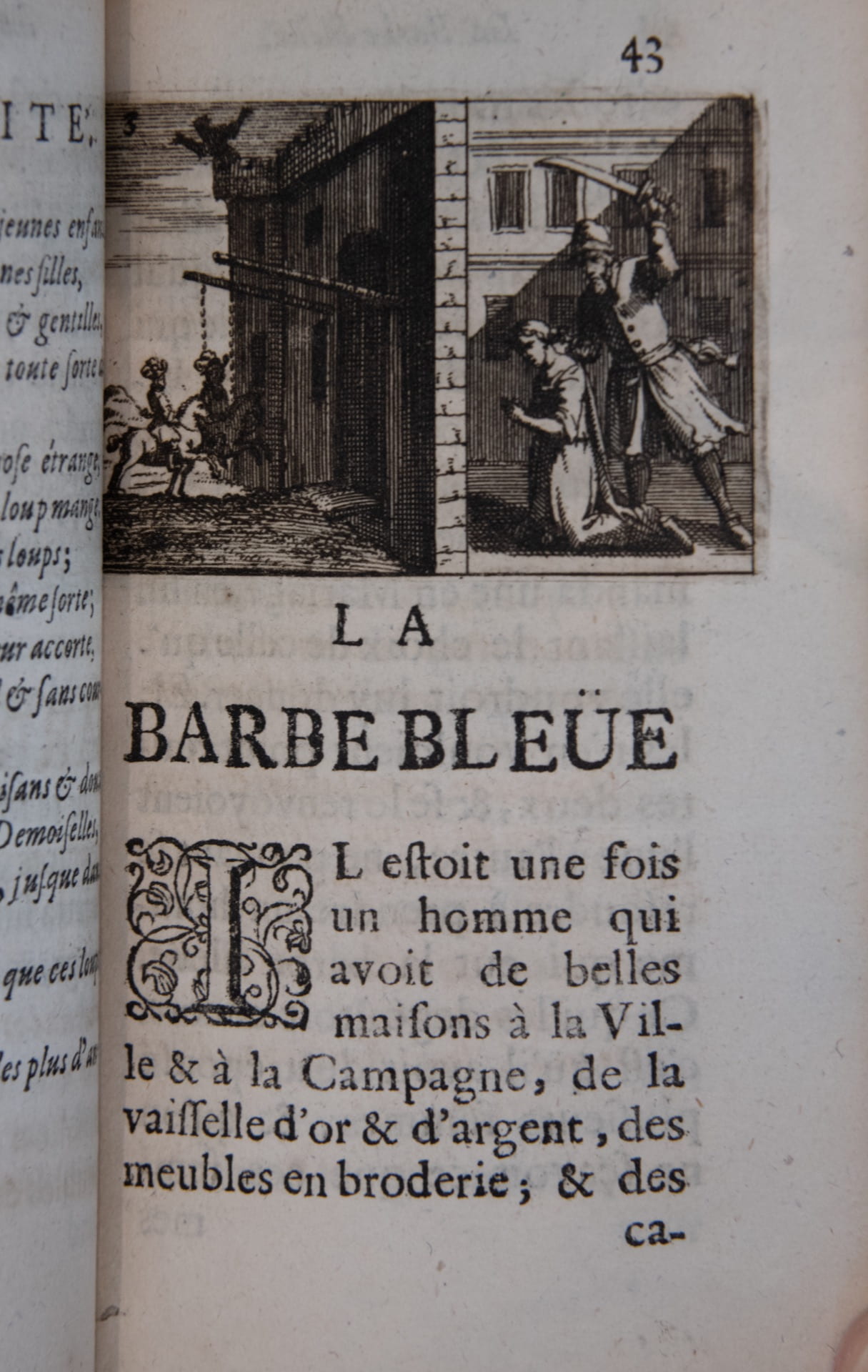

Bluebeard, a French fairy tale first published in Charles Perrault’s 1697 Histoires du temps passé, ou, Les contes de ma Mère l’Oye, known in English as The Tales of Mother Goose, has been retold over and over again, and deeply affected the development of the gothic and horror literary genres. It is the most well-known of a group of similar stories, including an English variant referenced long before Perrault in both The Faerie Queene (Spenser, 1590) and Much Ado About Nothing (Shakespeare, c. 1599). Its influence pervades Western canonical literature like Charlotte Bronte’s Jane Eyre and Daphne du Maurier’s Rebecca. Not just a relic of the past, references to Bluebeard also permeate recent films, including Ex Machina (2014), Crimson Peak (2015), and Get Out (2017).

Dartmouth Library’s illustrated book collections also highlight a curious trend: published depictions of Bluebeard, a French fairy tale, became highly Orientalized over time. The illustrations in the first literary versions were either decidedly European or included too little detail to be tied to a specific setting. The characters were also largely unnamed (apart from Bluebeard himself and the new bride’s sister, Anne). But in the late 18th century, amidst growing fads for the “Oriental,” Michael Kelly and George Colman the Younger created a new adaptation of the story for the London stage. “Blue Beard; or, Female Curiosity!” (1798) included characters named Abomelique, Fatima, Irene, and Selim, and was relocated to Turkey. This reimagining of Bluebeard as an exotic Turkish despot was an instant hit.

As an artistic trend, Orientalism’s presence in “Western” art is extensive, but this story’s visual legacy is a specific and disquieting case study. It seems that Kelly and Colman’s adaptation managed to tap into the wrong idea at just the right time for it to take hold. The character of Bluebeard as racial Other flourished in the West, generating a series of Orientalist interpretations that persisted well into the 20th century.