Varujan Boghosian, American, 1926–2020

The Fall of Icarus (The Oasis)

1991

Construction/collage

Overall: 14 7/8 × 12 ½ in. (37.8 × 31.8 cm)

Gift of Jane and Raphael Bernstein; 2010.84.19

Boghosian’s The Fall of Icarus (The Oasis) is an enigmatic work, as it contains no obvious allusions to the myth or to an oasis, defined by the presence of water. A lone tree stands in the center of the desert-like antique paper, with a butterfly floating downward just below the “oasis” of the tree. The title and composition of the work present dual subjects—the fall of Icarus and the oasis—that are in tension with one another. How can the fall of Icarus, a tragedy, be compatible with an oasis, a sanctuary? The absence of water in a reference to a mythological drowning and the life-sustaining resource of an oasis heightens the paradox of the work. By placing the myth in this surreal landscape, Boghosian challenges viewers to consider the relationships between the seemingly disparate motifs—Icarus and oasis, desert and sanctuary, living butterfly and ancient myth.

Varujan Boghosian, American, 1926–2020

The Fall of Icarus

1991

Construction/collage

Overall: 18 7/8 × 11 3/8 in. (47.9 × 28.9 cm)

Gift of Jane and Raphael Bernstein; 2010.84.18

Varujan Boghosian’s The Fall of Icarus incorporates found objects and layered constructions to recontextualize the myth of Icarus as a Surrealist collage. Boghosian’s work often invokes classical and literary traditions, so The Fall of Icarus is one of many inspirations including work by Orpheus and Eurydice, James Joyce, Emily Dickinson, Robert Frost, and William Blake. As a Dartmouth professor (1968–1995) with a studio in the English department, Boghosian embodies this intersection of literature, myth, and visual representation. The Fall of Icarus, juxtaposing the soothing, aged tree and paper with the torn bird, is characteristic of Boghosian’s subtle humor and “nostalgic, fragile charm” (as the New York Times put it). What does it mean for Boghosian to recast the myth with none of its recognizable features? The bird could potentially symbolize Icarus, but Boghosian leaves this to the viewer to consider as he engages us with this mystery.

Varujan Boghosian, American, 1926–2020

The Fall of Icarus (For W. H. Auden)

1993

Construction/collage

Overall: 12 ¼ × 9 ¼ in. (31.1 × 23.5 cm)

Gift of Jane and Raphael Bernstein; 2010.84.21

Boghosian’s collage The Fall of Icarus (For. W. H. Auden) shares some compositional similarities with his other two Icarus collages in this exhibition—backgrounds of aged paper and swathes of blue cutouts or the presence of butterflies. The collage’s dedication to Anglo-American poet W. H. Auden situates it directly in an artistic and literary lineage involving the Icarus myth. Auden’s poem “Musée des Beaux Arts” describes the scene of Renaissance artist Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s painting Landscape with the Fall of Icarus (also on view in this exhibition). Boghosian’s work eschews a direct portrayal of the falling Icarus, but it does incorporate a significant motif from both Auden’s poem and Bruegel’s painting: the ship that, in Auden’s words, “sailed calmly on” in the face of Icarus’s tragedy. Using the ship, Boghosian’s collage engages in dialogue with these other artists, evoking the same theme of indifference and questioning the significance of Icarus’s fall.

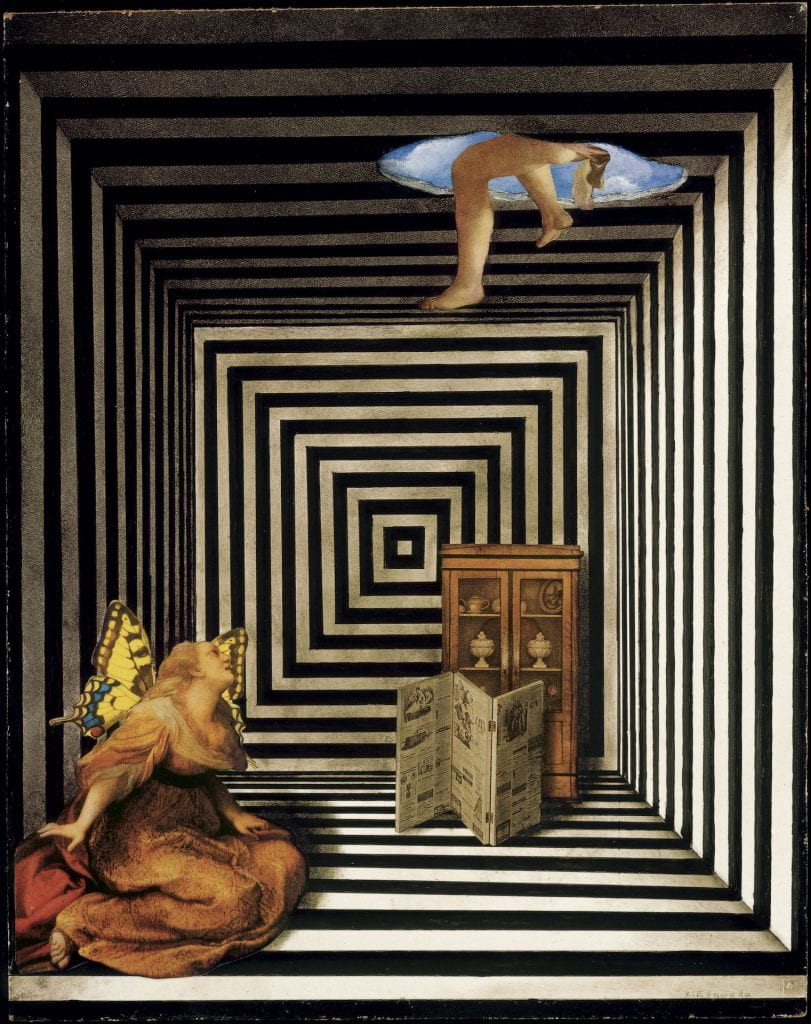

Xavier Esqueda, Mexican, b. 1943

The Relatives of Icarus (Los Parientes de Icaro)

About 1965

Oil and collage on composition board

Overall: 14 5/8 × 11 ½ in. (37.2 × 29.2 cm)

The artist; sold to present collection; P.965.105

Xavier Esqueda’s collage is a stylistic and thematic pastiche combining aesthetic elements of Surrealism and the Renaissance with natural, mythological, and modern imagery. In this dizzying, illusionistic space, Esqueda has reimagined the Icarus myth as an escape rather than as a fatal fall. The likely protagonist, unseen except for his legs, almost appears to be rising upward through a hole in the geometric ceiling. A kneeling woman looks on in despair, and with this figure, Esqueda adds a new character to the Icarus myth, which does not traditionally include women. Who is she? The collage’s title, The Relatives of Icarus, offers viewers a clue—perhaps she is Icarus’s mother. Has the artist shifted the myth’s focus from Icarus himself to those left behind in the wake of his tragic end? Esqueda experiments with both geometric perspectives and human ones as he reinterprets the ancient Greek tale.

Henri Matisse, French, 1869–1954

Icarus, plate VII from the illustrated book Jazz

1947

Pochoir

Image: 16 ½ × 10 ¼ in. (41.9 × 26 cm)

Sheet: 16 ½ × 25 3/16 in. (41.9 × 64 cm)

Gift of Lila Acheson Wallace, 1983; 1983.1009(8)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

© 2021 Succession H. Matisse / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

French printmaker, sculptor, and painter Henri Matisse created Icarus for his illustrated book Jazz using whimsical paper cutouts in vivid, solid colors. Matisse’s Icarus is a darkened silhouette who appears to be floating in the star-studded night sky. But why is Icarus floating in the night sky, when the Icarus of the original Greek myth is known for his tragic fall after the hot afternoon sun melted his wings? Is Icarus is ascending into the heavens after his fatal fall? Notably, there is no sign of Icarus’s infamous wings, no sign of the dangerous sea below, no sign of his tragedy—this Icarus is almost peaceful. Close observers can also spot a small red cutout, right where Icarus’s heart should be, contributing to the puzzling mysteries of Matisse’s mythology.

James Gillray, English, 1756–1815

The Fall of Icarus

1807

Hand-colored etching on paper

Sheet: 13 ½ × 9 in. (34.3 × 22.9 cm)

Gift of Jane and Raphael Bernstein; 2010.84.71

James Gillray, English satirist and printmaker, casts the contemporary politician Lord Temple, former Joint Paymaster of the Forces, as the foolishly ambitious Icarus. Lord Temple flaps uselessly after his father, Lord Buckingham, who flies ahead of his son with wings labeled “Tellership of the Exchequer.” In this biting reimagination of the Icarus myth, King George III is the sun, watching sternly as his rays melt Temple’s wings. Lord Temple opposed the King’s position on Catholics serving in the military and later lost his job. Temple allegedly stole office supplies as he left his post, forming the quills and wax of his wings. As the overweight bureaucrat tumbles toward a stake reading “out of the public hedge,” viewers are informed that both the King and the people are better off for this proud Icarus’s end.

Pieter Bruegel, Dutch, about 1527/28–1569

Landscape with the Fall of Icarus

About 1555

Oil on canvas

Overall: 29 × 44 in. (73.5 × 112 cm)

Museum of Fine Arts, Belgium; Inv. 4030

Landscape with the Fall of Icarus is attributed to the Dutch Renaissance painter Pieter Bruegel the Elder. The painting is a busy, lively depiction of the tragic Icarus myth. Viewers must look closely to see the titular figure plunging into azure waters—only his kicking legs are visible. Other figures—a plowman tilling his field, a shepherd gazing upward at the sky, and a fisherman—are more readily apparent. None of these characters seem to notice the struggling Icarus.

These figures, and the ships passing by the drowning boy, raise the question of whether Icarus’s death was really an unavoidable consequence of his own actions. Rather than faithfully depicting the original myth, which was centered upon the two characters of father and son, Bruegel chose to set his Icarusscene within a social landscape. In doing so, Bruegel implicates others in a tragedy traditionally held to be Icarus’s own fault.

You must be logged in to post a comment.