“Myth must be kept alive. The people who can keep it alive are the artists of one kind or another.”

– Joseph Campbell, author of The Power of Myth

Why do ancient myths endure? Why do we continue to resurrect and recycle these stories, rather than exclusively creating new ones or focusing on the myriad forgotten or little-known histories we could preserve instead? Myths have long been a source of inspiration for creative expression in the arts, perhaps because the various versions and interpretations of a single myth open interpretive space for artistic experimentation. The Icarus myth is one story that has fascinated artists throughout history and remains popular in contemporary visual art, literature, and music.

The story of Icarus originated in Greek antiquity, but its best-known written version comes from the Roman poet Ovid’s Metamorphoses (about 8 CE). Icarus and his father, Daedalus, were imprisoned, so Daedalus, an inventor, fashioned metal and wax wings to aid them in an escape. Daedalus cautioned his son not to fly too close to the sea or the sun, which would destroy his wings. The youthful, brash Icarus lost himself in the joy of flight and soared too high. The sun melted the wax of his wings, plunging him into the sea below. The story is undoubtedly tragic, but the Greek mythological universe is filled with such tragic (and more overtly heroic) stories, so what about this myth continues to fascinate and inspire artists from 16th-century Europe to 21st-century America?

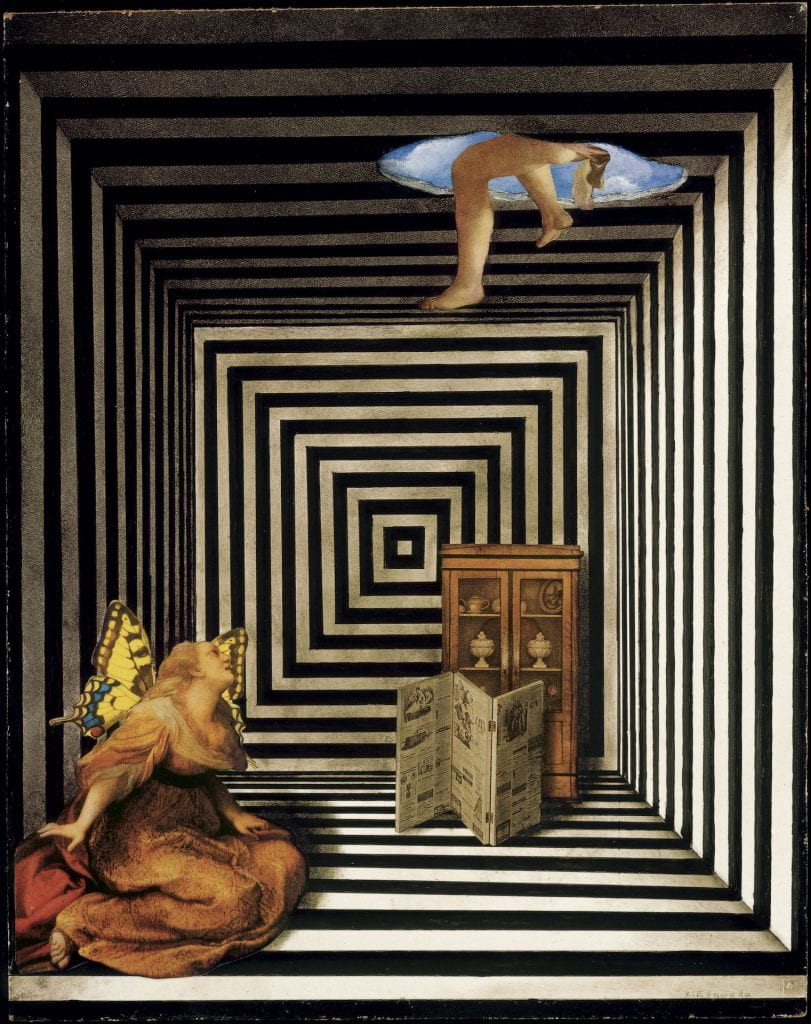

Surrealist sculptor and collage artist Varujan Boghosian (1926–2020) employed the Icarus myth to foster a revitalized interpretive space within the ancient story. Boghosian created three collages (currently in the Hood Museum of Art’s collection) centered upon Icarus and also several other collage interpretations of the myth, including a 1986 version and one in 2008. His use of collage as a medium for Icarus retellings mirrors the aggregated, constructed nature of myth, which grows from its original form to include associations from later years as it is told throughout history. Other artists have also represented Icarus in collage, such as Henri Matisse, whose Icarus, plate VII from the illustrated book Jazz (1947), seems to dance or float against a night sky. Xavier Esqueda, a Mexican artist whose style incorporates elements of Surrealism, Abstract Expressionism, and Pop Art, exaggerates the assembled quality of his artistic narrative in The Relatives of Icarus (Los Parientes de Icaro) (about 1965). Esqueda’s illusionistic, geometric space features an Icarus who appears to escape, rather than fall, as a woman looks on mournfully. In all three of these artists’ works—Boghosian, Matisse, and Esqueda—the medium of collage allows for the addition and subtraction of different elements to yield transformative interpretations of the same story. Matisse uses the background of his construction to recast Icarus at night, and Esqueda adds an “unreal” dimensionality and a female figure who is not present in the myth’s canonical plot.

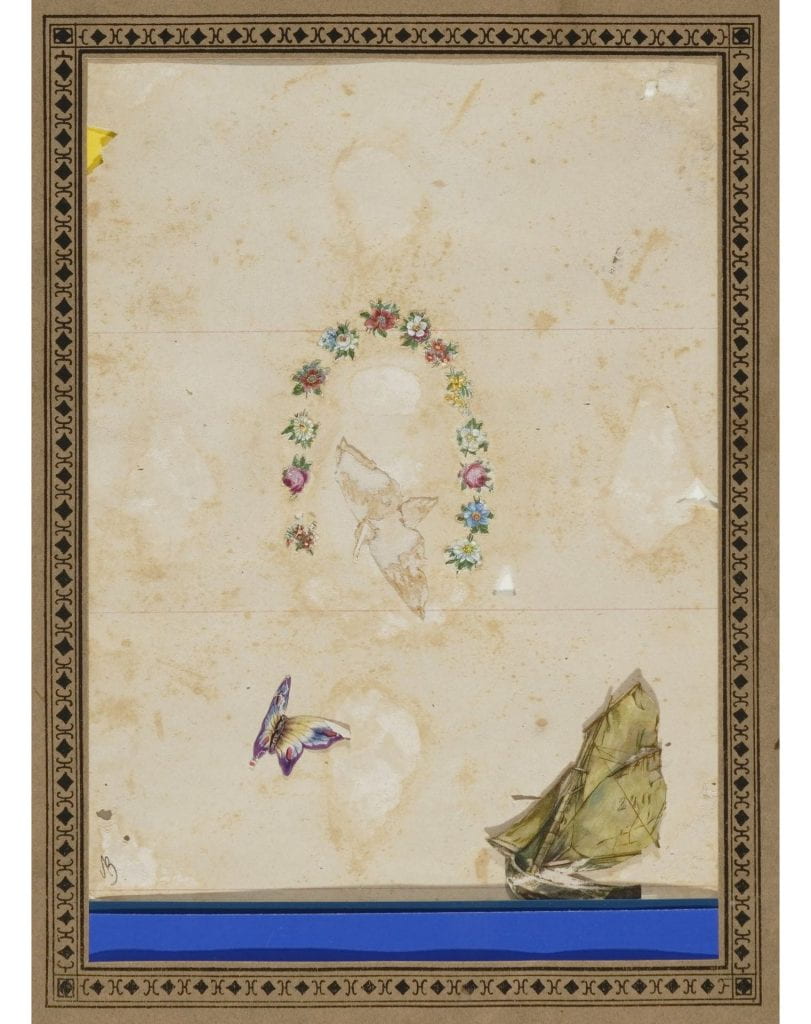

Varujan Boghosian, American, 1926–2020

The Fall of Icarus (For W. H. Auden)

1993

Construction/collage

Overall: 12 ¼ × 9 ¼ in. (31.1 × 23.5 cm)

Boghosian also uses the Icarus myth to engage in an artistic dialogue across Western cultures, centuries, and continents. He dedicates his 1993 collage The Fall of Icarus (For W .H. Auden) to one of the most renowned poets of the 20th century, nearly twenty years after Auden’s death. Two of Boghosian’s other collages in this exhibition, The Fall of Icarus (1991) and The Fall of Icarus (The Oasis) (1991), allude to the same subject matter, but The Fall of Icarus (For W. H. Auden) uniquely situates Boghosian in the artistic tradition of the Icarus myth. W. H. Auden’s 1939 poem “Musée des Beaux Arts,” presents a retelling of Icarus’s fall, but the poem does so through the lens of another artist: Pieter Bruegel the Elder. Bruegel’s painting Landscape with the Fall of Icarus (about 1555) presents Icarus’s tragedy as being eclipsed by the indifference of surrounding characters, which Auden observes, noting “How everything turns away/ Quite leisurely from the disaster” (Auden ll.14–15).

Returning to Boghosian, by titling his work “For W. H. Auden,” the artist has not only retold the story of Icarus in his own interpretation, he has also retold Auden’s story of Bruegel’s version. Why has Boghosian chosen to do so, and for that matter, why did Auden? Are these artists paying tribute to their predecessors? In working from a common source myth to produce individual interpretations, are they engaging in a form of artistic competition or perhaps emulation? Boghosian’s only clear reference to the myth in this work is a ship, a feature of Bruegel’s work that “sailed calmly on” (Auden l.21) in the face of Icarus’s tragedy, but it is not present in the original myth. However, there is no Icarus to be found in Boghosian’s collage, or in his other two Icarus works in this exhibition; there is only a wreath of flowers, a butterfly, and the faintest outline of a bird. Boghosian has retained the symbol of indifference—the ship—but erased the tragedy, leaving only its echoes in his title. The Fall of Icarus (For W. H. Auden) is therefore more a retelling of this artistic tradition of the myth than the story of Icarus itself.

Henri Matisse, French, 1869–1954

Icarus, plate VII from the illustrated book Jazz

1947

Pochoir

Image: 16 ½ × 10 ¼ in. (41.9 × 26 cm)

Sheet: 16 ½ × 25 3/16 in. (41.9 × 64 cm)

Gift of Lila Acheson Wallace, 1983; 1983.1009(8)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

© 2021 Succession H. Matisse / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Musée des Beaux Arts (Excerpt) W.H. Auden In Breughel's Icarus, for instance: how everything turns away Quite leisurely from the disaster...the sun shone As it had to on the white legs disappearing into the green Water; and the expensive delicate ship that must have seen Something amazing, a boy falling out of the sky, Had somewhere to get to and sailed calmly on.

Poetic references to visual art are not uncommon, occurring often enough for the term ekphrasis to exist describing the phenomenon. But the attraction poets have felt toward the Icarus myth, and Bruegel’s artistic rendering in particular, is notable. William Carlos Williams, Puerto Rican–American poet and a contemporary of Auden’s, posthumously received the Pulitzer Prize for his collection Pictures from Bruegel (1962). This work features his poem “Landscape with the Fall of Icarus” and focuses similarly on the indifference—the “splash quite unnoticed” (Williams l.19)—that the surrounding characters express towards Icarus. Anne Sexton, another 20th-century American poet and Pulitzer Prize winner, interpreted the myth in “To a Friend Whose Work Has Come to Triumph” (1960). Sexton takes a satirical approach to the classic tale, viewing Icarus as “acclaiming the sun . . . while his sensible daddy goes straight into town” (Sexton ll.13–14). Though it may seem incongruous with the subject matter of the myth, Sexton is not the only artist to treat Icarus humorously. James Gillray, an 18th-century British caricaturist and printmaker, used Icarus to mock bloated former bureaucrat Lord Temple. Parody may seem like a far cry from the original tragic tenor of the story, but these artists demonstrate the malleability of the mythic structure in conveying meaning.

As New Yorker critic Doreen St. Felix observes, “Influential art has always spawned second lives that appear to contradict their origins.” Humor is one way artists have perpetuated the tragic myth in a seemingly contradictory fashion, but this notion of subversion or reinvention is another manner in which myths endure. The original Icarus myth could be seen as a moralization against pride, but artistic interpretations challenge this view. Do we admire Icarus for his daring instead of condemning his pride? Anne Sexton certainly admires him, and Auden, Williams, and Bruegel blame bystanders more for the tragedy than they do Icarus. Matisse, Boghosian, and Esqueda also portray Icarus in a more reflective than critical fashion. This constellation of differing interpretations is another reason this particular myth is unique. Unlike other Greek mythological heroes, who were kings or half-gods who fought monsters, Icarus was a normal boy, making his fall a story of human vulnerability. Tales about heroes fighting monsters do engender allegorical meaning, but the Icarus myth is especially compelling because it is centered upon our human flaws and strengths, our greatest aspirations and our most painful shortcomings. No wonder our collective cultural memory refuses to leave Icarus behind.

Browse all works in exhibition: click here to learn more about each image.

You must be logged in to post a comment.