Humans Meet Metal

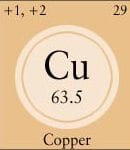

Between seven and ten thousand years ago, our early ancestors discovered that copper is malleable, holds a sharp edge, and could be fashioned into tools, ornaments, and weapons more easily than stone, a discovery that would change humanity forever. This meeting of humans and metals would be the first step out of the Stone Age and into the ages of metals: the Bronze and Iron Ages. Thus began the increased movement of elements and minerals out of their parent geological formations and into the air, soil, water, and living organisms by way of smelters, furnaces and mine tailings.

The first several thousand years of copper production contributed little to global or even local pollution. Copper is not very toxic in comparison to other metals and early humans used too little of it to begin concentrating it in soil, air, or water to the extent that it would affect human health or ecosystems. It appears that during the first few thousand years of its use, humans experiment with and learned techniques to utilize copper. As they got better at working with it, civilizations became more complex, which in turn often enabled better copper-working technology. With this came expanded use of copper and a greater movement of copper into our everyday environment.

Metallurgy is Born

Gold is believed to have been used earlier than copper, though its softness and scarcity made it impractical for widespread use, whereas copper is harder and found in pure form (“native copper”) in many parts of the world. (Gold and copper’s distinct colors and existence in pure form made it easy for our early ancestors to distinguish the two metals from other minerals and stones they came across.)

There is disagreement among archaeologists about the exact date and location of the first utilization of copper by humans. Archaeological evidence suggests that copper was first used between 8,000 and 5,000 B.C., most likely in the regions known now as Turkey, Iran, Iraq and — toward the end of that period — the Indian subcontinent. Archeologists have also found evidence of mining and annealing of the abundant native copper in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan in the United States dating back to 5,000 B.C.

Native copper was likely used first, as it did not require any process to purify it. It could have been hammered into shapes although it would have been very brittle. Annealing was the first step toward true metallurgy, when people discovered that copper became more flexible and easy to work with when it was heated before hammering. Next, casting of molten copper into molds was developed. At some point humans discovered copper ore and — possibly by accident — that the ore could be heated to very high temperatures in a low-oxygen environment to melt out the pure copper, a process known as smelting. This lent more flexibility to copper crafting; no longer was native copper the only kind of useful copper if copper could be extracted from ores.

Innovative Egyptians

The Sumerians and the Chaldeans living in ancient Mesopotamia are believed to be the first people to make wide use of copper, and their copper crafting knowledge was introduced to the ancient Egyptians. The Egyptians mined copper from Sinai and used it to make agricultural tools such as hoes and sickles, as well as cookware, dishes, and artisans’ tools such as saws, chisels, and knives. The Egyptians, famously fond of personal beautification, made mirrors and razors out of copper and produced green and blue makeup from malachite and azurite, two copper compounds with brilliant green and blue colors.

By comparing the purity of copper artifacts from both Mesopotamia and Egypt, scientists have determined that the Egyptians improved upon the smelting methods of their northern neighbors in Mesopotamia. Most copper items in Egypt were produced by casting molten copper in molds. The Egyptians appear to have been one of several groups that independently developed the “lost-wax” method of casting, which is still used today. (Put simply, wax is formed into the shape of the end product, then covered in clay. The wax is melted out leaving a clay mold, which is then filled with molten copper. The mold is broken off when the metal is cool.)

Bronze is Better

The Egyptians may have been the first group to discover that mixing copper with arsenic or tin made a stronger, harder metal better suited for weapons and tools and more easily cast in molds than pure copper. (Since copper ore often contains arsenic, this may have been the unintentional result of smelting copper ore that included naturally occurring arsenic.) This alloy of copper with arsenic or tin is called bronze, and there is archeological evidence that the Egyptians first produced bronze in 4,000 B.C. Bronze may have also been developed independently in other parts of the Middle East and other parts of the world. Regardless of where it originated, bronze metallurgy soon overtook copper in many parts of the globe, thus ushering in the Bronze Age. (In parts of the world that lacked deposits of tin, copper was used alone or alloyed with other metals until iron was introduced.)

The smelting process for bronze made with arsenic would have produced poisonous fumes. People may have preferred tin-based bronze or found that it was easier to control the amounts of tin added to copper than it was to control the amount of arsenic, which often occurred naturally in copper ore. Whatever the reason, bronze made with tin soon became the bronze of choice throughout the Middle East.

Tin deposits were more confined to certain geographical areas than copper, which was readily available in many parts of the Middle East as well as other parts of the world. As people began using bronze instead of pure copper to make weapons and tools, trade in tin developed. The availability of bronze led to more advanced tool and weapon making, and with better weapons, armies could better conquer neighboring societies (and plunder their tin and copper resources).

The island of Cyprus in the Eastern Mediterranean was a major destination for European and Middle Eastern Bronze Age people looking to buy or loot copper. Cyprus was the major supplier of copper to the Roman Empire. The name “copper” is probably derived from the Latin “aes Cyprium,” meaning “metal of Cyprus.” However, some speculate that the name “Cyprus” may have come second; it may have been derived from an older word for copper.

Copper Crafting and Spirituality

As copper helped humans to advance warfare, it also has played a role in the religious and spiritual life of people around the world through time. Hathor, Egyptian goddess of the sky, music, dance and art, was also the patron of Sinai, the major copper mining region of the Egyptians; she was often referred to as “Lady of Malachite.”

To the people of the Andes in South America, who developed the most advanced metallurgy in pre-Columbian America, copper metallurgy was more than a secular craft for producing tools. Using native copper, Andean artisans made religious items from pounded copper foil and gilded copper.

In many pre-colonial sub-Saharan cultures as well, coppersmiths were believed to have powers as shamans, magicians, and priests because of their intimate knowledge of earth, minerals, and fire and their ability to produce metal from ore. In some parts of the continent coppersmithing was an inherited position with master smiths passing secret knowledge on to their sons. Mining, smelting, and casting of copper ore were preceded by elaborate ceremonies to ensure that the endeavors were safe and fruitful.

Copper also plays a role today in many New Age beliefs. In some modern religions, it is seen as having healing powers, both spiritually and physically. Some people wear copper to help alleviate the symptoms of arthritis.

Bronze Buddhas and Copper “Cash”

The people of the Indian subcontinent have been using copper and its alloys as long as anyone. Bronze casting was extensive in ancient times and bronze was used for religious statues and artwork. This practice also spread to Southeast Asia where copper and its alloys are used extensively even today in Buddhist artwork.

Copper was first used in China around 2500 BC. The Chinese quickly began using bronze as well, and used different percentages of tin in bronze for different purposes. They used copper and bronze extensively for coinage. During the flourishing economic activity and expanded foreign trade in the Sung dynasty, circa 900 to 1100 AD, the use of cash—round copper coins with a square hole in the middle—exploded. Copper production was now reaching almost industrial proportions in some civilizations, though probably nowhere more than in ancient Rome.

The Romans: Precocious Polluters

Although iron and lead were in use by the era of the ancient Romans, copper, bronze, and brass (an alloy of copper and zinc) were used by the Romans for coins, aspects of architecture such as doors, and some parts of their extensive plumbing system (although pipes were made of lead). They also developed pipe organs made with copper pipes.

The Romans controlled extensive copper deposits throughout their empire. Scientists analyzing copper isotopes and trace metals present in Roman copper coins have determined that Rio Tinto, Spain (still a working copper mine), Cyprus, and to a lesser extent Tuscany, Sicily, Britain, France, Germany and other parts of Europe and the Middle East were sources of copper for the Empire. Increased purity of Roman copper coins over time also shows that their smelting methods improved quickly.

The Romans in their heyday produced nearly 17,000 tons of copper annually, more than would be produced again until the Industrial Revolution in Europe. With this enormous output of copper came pollution that would be unsurpassed for almost two thousand years when the Industrial Revolution began. Did polluted air from early copper smelting affect the health of humans living in ancient times? Probably. Early smelting methods at that time were crude and inefficient by the standards of today. Copper smelting and to a lesser degree copper mining produced ultra-fine particle dust that was carried into the atmosphere on air currents created by the intense heat from smelting operations. Most of the pollution would have fallen near the smelting sites, causing health problems and contaminating soil and water.

Scientists in the 1990s discovered that copper contamination is present in 7,000-year-old layers of ice in the Greenland glacial caps. A layer of ice is deposited on glacial caps annually, allowing a year-by-year analysis of the ice composition. As copper smelting became widespread at the beginning of the Bronze Age, enough copper was released into the air to contaminate ice thousands of miles away. Peaks in copper concentrations in ice layers correspond to the era of the Roman Empire, the height of the Sung dynasty in China (c. 900-1100 AD), and the Industrial Revolution, with decreased concentrations found in ice deposited immediately after the fall of the Roman Empire and during the later Middle Ages of Europe, when copper and bronze use was lower.

The copper pollution of the Roman days still haunts us today. One former Roman copper mine and smelting site in Wadi Faynan, Jordan is still — two thousand years after it ceased operations — a toxic wasteland littered with slag from copper smelting. Researchers have discovered that vegetation and livestock in Wadi Faynan today have high copper levels in their tissue.

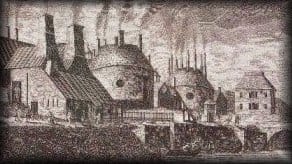

The Industrial Revolution: Picking up Where the Romans Left Off

Beginning in the late 1600s, copper smelting became a major industry in Great Britain. Copper ore from Cornwall and other areas and coal deposits throughout the country fueled the smelting of copper. An abundance of coal in Swansea, Wales made this coastal town a prime location for Britain’s copper smelting activities beginning in early 1700s. The copper industry drove the economy of this town. Wealthy English people often owned smelters, while local Welsh people worked as laborers in the industry. Just as in ancient Rome, copper smelting had its price. The town and once lush countryside surrounding Swansea was stripped of vegetation by noxious copper smoke that billowed from the smelter stacks and settled on the surrounding town and fields. Topsoil on denuded hillsides succumbed to erosion. Livestock developed strange new ailments like swollen joints and rotten teeth. Farmers blamed the smoke. The smoke also reportedly caused shortness of breath, decreased appetite, and other complaints in humans.

The Cornish copper ore purified in the Swansea smelters was high in arsenic, sulfur, and fluorspar (a compound of the element fluorine). The smelters emitted fumes from these compounds along with exhaust from the coal that fired the operations. The sulfur and fluorspar from the smoke mixed with water and oxygen in the atmosphere to produce sulfurous, sulfuric and hydrofluoric acids which rained down on Swansea as acid rain. Copper slag and other waste covered the landscape near the smelters.

In 1821, a fund was set up in Swansea, with contributions from some of the smelter owners, that would go to whomever could develop the technology to reduce the level of poisons being emitted from the smelters. (The industrialists were likely more concerned with economics and aesthetics than the health of workers and local people.) Although several groups of people came up with ideas to purify the smoke, none succeeded.

Eleven years later, a group of Welsh farmers from outside Swansea sued one of the major smelter owners for public nuisance, claiming that the smelter smoke was damaging their farms. The owner of the copper smelter hired one of the best lawyers in the country, who fought the plaintiffs on the basis that the town depended on the copper industry for its economic survival and that the crop failures and sick livestock were the result of the Welsh people’s backward farming methods and the disagreeable Welsh weather. The farmers lost the suit.

Conductive Copper

Copper played a central role in the technologies developed during the industrial revolution. One of the most important uses of copper at that time was in electrical engineering. Early scientists experimenting with electricity chose copper as a transmitter because it is highly conductive (can transmit electrical current easily). The electrical engineering industry today is the second largest consumer of copper.

The Price of Industrialization

Although production methods have improved since the time of the Romans and the Industrial Revolution, today copper production makes a hefty contribution to global pollution.

Butte, Montana is home of an abandoned copper mine once owned by the now defunct Anaconda Copper Mining Company, established in Butte in 1895. Until the major Butte mine operations closed in the 1980s, the mine produced 20 billion pounds of copper. Until the 1950’s, it produced one third of the country’s copper and was an important supplier for the nation during the two World Wars. The former mine is now the largest Superfund site in the country. The main open pit has filled with water since the termination of mining activities, forming a 600-acre lake. Copper, lead, cadmium and arsenic contaminate the huge pit, which is recharged with water every day from an aquifer below—making the toxic lake nearly impossible to clean up. Sulfur, a mineral that is commonly a component of copper ore, reacts with air and water, producing sulfuric acid, which fills the pit. Mine runoff and fallout from the smelter once owned by Anaconda cover the landscape. A 1,000-acre tailings pond sits near the main pit.

During its operation, the copper mine in Butte shaped the social fabric of the town. Anaconda Copper Mining Company had a heavy hand in Montana politics and had a direct effect on the lives of miners and their families. Life in Butte during most of the 20th century revolved around anticipating layoffs and strikes that came at the end of three-year contracts between Anaconda Company and the miners’ union. Working conditions were terrible. Mining accidents, “miners’ lung,” heavy pollution, and violence and unrest between unions and the company were some of the costs to the people of Butte. Although little copper mining is still going on in the town, citizens of Butte are left with the toxic legacy of the mine.

The Anaconda Company also owned a massive copper mine in Chuquicamata, Chile that operated from the 1920s to the 1970s. Chilean mine laborers lived in tiny company-owned apartments with minimal plumbing facilities. Wives and family of miners waited in lines daily for access to the meager provisions at the company store designated to the lowest class of mine employees. Their employment status also dictated which schools their children could attend. Strikes were also a regular part of life for miners and their families. Ethnographer and Butte, Montana native Janet Finn writes, “In establishing labor, community, and government relations in Chuquicamata, the company turned to tried and true methods practiced in Butte: blacklists, bribery, and occasional brute force tempered with amusements that embraced both vice and virtue.”

Anaconda Company’s Chuquicamata mine was closed in 1971 after the Chilean government nationalized the country’s copper resources. However, copper mining is still a major industry in Chile. A University of Chile study in 1999 showed that copper mining, smelting, and refining accounts for a significant portion of the greenhouse gas production and other air pollution in that country and accounts for the largest consumption of fossil fuels in Chile as well as a significant amount of electricity. This contributes to global carbon dioxide levels, which contribute to global warming. Additionally, during the smelting process, large quantities of sulfur dioxide (SO2), a precursor to acid precipitation, are released from the sulfide ores, the most commonly mined copper ores in Chile.

Local Copper Mining

Several towns in central Vermont’s Orange County were sites of small copper mines and smelting operations during the 1800’s. None of the mines produced as much copper as the major mines in other parts of the country, but the local mines were a source of employment for Cornish and Irish immigrants and helped support the local economy. Ely (now Vershire) was a classic “boom and bust” mining town, the site of one of the larger copper mines in the area and the scene of two “Ely Wars” between miners and mine owners in which miners rioted to get back-pay owed to them by the failing mining company.

Another local copper mine was the Elizabeth Mine in South Strafford, Vermont that was in operation from 1830 to 1958. Today, it is part of the Environmental Protection Agency’s Superfund program.

Sources Include:

- Green Mountain Copper: The Story of Vermont’s Red Metal by Collamer Abbott, published by the Herald Printery, Randolph, Vermont, 1973.

- Red Gold of Africa by Eugenia W. Herbert, published by the University of Wisconsin Press, Madison, 1984.

- “Early Central Andean Metalworking from Mina Perdida, Peru” by Richard L Burger and Robert B Gordon in Science, New Series, Vol. 282, No. 5391, pages 1108-1111, November 6, 1998.

- Sixty Centuries of Copper by B Webster Smith, published by Hutchinson of London for the Copper Development Association, 1965.

- “Cyprus Lives in Love & Strife” by Robert Wernick in Smithsonian, Vol. 30, Issue 4, July 1999.

- “Copper, Prized Through the Ages,” by Jeffrey A Scovil in Earth, Vol. 4, Issue 2, April 1995.

- “Copper” by Donald G Barceloux in Clinical Toxicology, Vol. 37, No. 2, pages 217–230, 1999.

- “Ancient Metal Mines Sullied Global Skies” by R Monastersky in Science News, Vol. 149, Issue 15, April 13, 1996.

- “Long Term Energy-Related Environmental Issues of Copper Production” by S Alvarado, P Maldonado, A Barrios, I Jaques in Energy, Vol. 27, Issue 2, pages 183-196, February 2002.

- “How Rome Polluted the World” by David Keys in Geographical, Vol. 75, Issue 12, December 2003.

- “The Great Copper Trials” by Ronald Rees in History Today, Vol. 43, Issue 12, December 1993.

- “Arsenic Bronze: Dirty Copper or Chosen Alloy? A View from the Americas,” by Heather Lechtman in Journal of Field Archaeology, Vol. 23, No. 4, pages 477-514, Winter, 1996.

- “A Penny for Your Thoughts: Stories of Women, Copper, and Community” by Janet L Finn in Frontiers, Boulder, CO, Vol.19, Issue. 2, page 231, 1998.

- “Pennies from Hell” by Edwin Dobb in Harper’s Magazine, Vol. 293, Issue 1757, October 1996.

- “Atmospheric Pollution and the British Copper Industry, 1690-1920” by Edmund Newell in Technology and Culture, Vol. 38, No. 3, pages 655-689, July 1997.