I find myself reacting quite negatively to two aspects of the way the White House and its allies are pushing the Raise the Wage agenda to build support for increasing the federal minimum wage from $7.25 to $10.10 per hour.

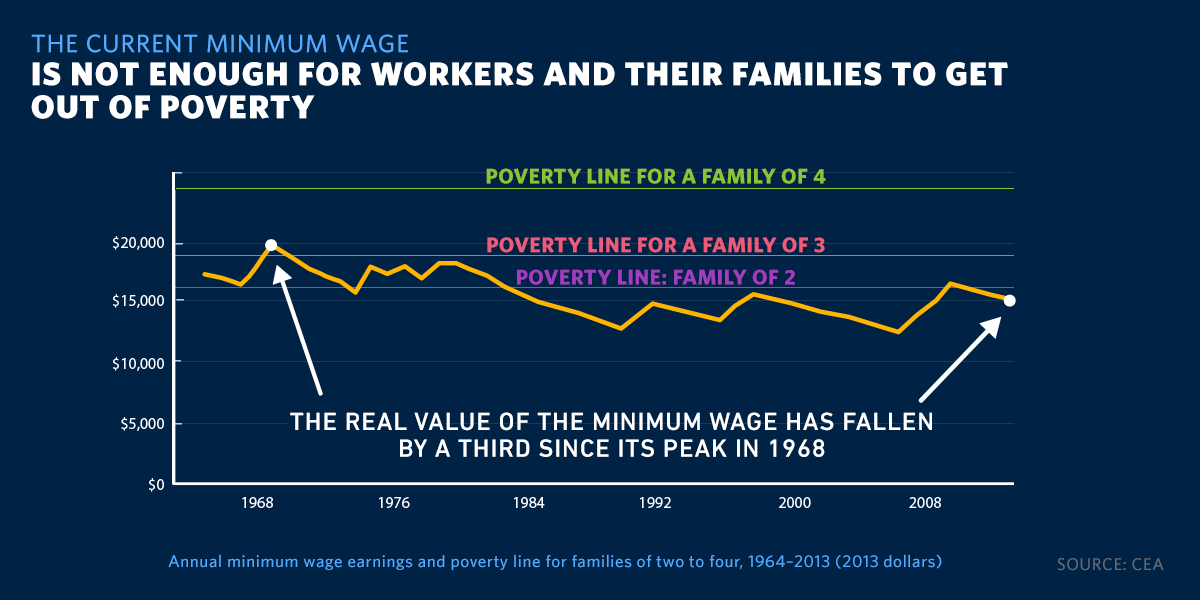

The first aspect is to compare the federal minimum wage to the poverty level without acknowledging that the Earned Income Credit provides income support for those with low incomes. The chart below gives an example from the White House webpage linked above:

The orange curve should be augmented by the appropriate EIC amount for the family type in question. In that case, we would see levels of income that are higher relative to the various poverty lines. That might or might not persuade you that the minimum wage is high enough, but it would give a fairer accounting of income relative to poverty and it would suggest another avenue for providing support.

The President's proposed FY15 budget includes provisions to expand the EIC and make more workers eligible. If income support is society's obligation, then it should be done through the tax code. There is no need to interfere with the workings of marketplaces, particularly in a way that discourages employers from creating the low-wage jobs that unskilled laborers depend on, to meet that obligation. Perhaps the Republicans will make that case and strike a deal -- adopt the higher EIC and the suggested mechanisms to pay for it and say no to the higher minimum wage.

The second negative aspect of this campaign is to produce narratives about single moms in which there is no discussion of the children's father's resources. Here's an example from an e-mail sent out today by Secretary of Labor Tom Perez:

Semethia's a 36-year-old single mom. Her son hopes to go to college one day. Her daughter wants to take gymnastics lessons. But with a service job that pays just $8.25 an hour, Semethia relies on food stamps and help from friends and family just to keep food on the table -- much less build the future she'd like for her kids.

That's all we learn about Semethia from the e-mail. You can find other vignettes in the popular press, like these two at the New York Times Motherlode blog. They are compelling stories. These moms are struggling, and they shouldn't have to go it alone.

What about the children's father? Why are his earnings and resources not being applied to alleviate the financial burden on his children? If he is deceased, there should be survivor benefits from Social Security. If he is not deceased but they are divorced, then there should be divorce agreement stipulating child support, and courts should actively ensure that child support is being paid. If they were never married and his resources are not being offered voluntarily, then the appropriate policy is to enhance the ability for courts and others to obtain child support. All of these issues should find their way into the public discussion.

Let me be clear. I am not saying that Semethia should be married to the children's father or that he should even be a presence in their lives. What I react negatively to is that the policy in question -- raising the minimum wage -- would presume to take resources from Semethia's employer, the employer's customers, or other potential employees at this employer without first taking the resources from Semethia's children's father. The minimum wage is a tax on employers who provide employment for people like Semethia whose best opportunities in the labor force generate output that is valued at only $8.25. I do not see the wisdom in making it harder for an employer to do that.