When the museum reopened in 2019, galleries with works by artists of primarily European descent were intentionally installed alongside galleries containing works by Native American artists. These adjacent galleries were designed to invite dialogue between objects and to serve as an invitation to consider America’s complex histories.

![[Right:] A view of the exhibition American Art, Colonial to Modern standing in the exhibition Portrait of the Artist as an Indian / Portrait of the Indian as an Artist, in Hartevelt Gallery. Photo by Michael Moran. [Left:] Portrait of the Artist as an Indian / Portrait of the Indian as an Artist (on view January 26, 2019–February 23, 2020), in Hartevelt Gallery. Photo by Jeffrey Nintzel.](https://sites.dartmouth.edu/meanwhileatthemuseum/files/2021/04/Vivian-Blog-Post_installations2-1024x301.jpg)

A fruitful discussion ensued about the shared experiences of both Euro-American explorers and Native American communities during this period. Four themes emerged that seemed to reflect these shared experiences: Encounter, Exchange, Expansion, and Endurance.

These themes became the new title of Ellen’s unit and the focus of her classroom study. They also evolved into four separate stops on a tour of the museum’s American and Native American galleries for more than 100 seventh grade Richmond Middle School students that year.

Encounter

Through a creative writing exercise, students considered the perspectives of both the lone white trader and three Plains warriors encountering one another for the first time in Frederic Remington’s painting, Shotgun Hospitality. What might this lone trader be considering as he scratches his chin and looks up at the visitors to his campfire? What might the men of this Plains culture be considering as they confront this stranger on their lands?

Exchange

For the theme of exchange, students explored a gallery of historic Native American objects to learn about the ways in which Indigenous technologies reflect an expansive understanding of resources available in the environment as well as the role of trade goods in adaptation and innovation.

For example, in this tiny jacket, a Sugpiaq woman used bear gut and sinew to construct a fully waterproof jacket for her child. During the 19th century, Indigenous technology for the construction of winter clothing was far superior to European forms. The maker chose to employ trade goods in the form of embroidery thread only in the embellishment. Thread provided opportunities for colorful creative expression beyond what was available in local natural materials. As a result of this stop, students learned that both explorers and Indigenous cultures had much to offer one another in their exchange of knowledge, goods, and services.

Expansion

Students then sketched Régis François Gignoux’s White Mountain Landscape—a fanciful, monumental image inspired by the great mountain ranges of the west—to consider the challenges faced by explorers in their travels. They also compared the attitudes expressed toward the land in this painting to those embedded in the objects by Native Americans makers. Consider the perspective of the viewer for this painting. Where would you need to stand in order to see this landscape from this point of view? What does this “eagle’s eye view” suggest about the painter’s attitude toward the lands stretching to the horizon? The natural world is honored in the form of flora and fauna and the representation of animals sewn, painted, and carved on objects made by Native American artists but “landscape” drawing and painting is not a historic Indigenous art form. Why might that be?

Endurance

Finally, to demonstrate that Native cultures endure and continue to advocate for their sovereignty, they spent time with Yatika Starr Fields’s painting, Buffalo Calf Women March, a tribute to the Native American women who organized the 2016 protests against the Dakota access pipeline. Consider the way the artist has split the composition into three parts, the mirroring of the landscape above and below, and the cropping of the women marching along the highway. How do these choices suggest the passage of time and the enduring resistance of Native cultures to encroachments on their lands?

Ellen Fisher, Richmond Middle School social studies teacher:

In thinking about what has traditionally been the Lewis and Clark unit, the question that came to mind was: Whose story is being told, and whose stories are being left out of the narrative? The conventional recounting of the Lewis and Clark expedition casts the explorers as the lead characters, the heroes, and the “discoverers” of the American west. In reality this land had been inhabited by people with sophisticated cultures and a deep understanding of the land for millennia. The answer to the question lay in refocusing this Euro-centric perspective by moving to center stage the people who played a pivotal role in the success of this journey of discovery.

Using contemporary and traditional Native American art and objects from the Hood Museum’s collection added an enriching dimension to the unit. It engaged students in higher order thinking and offered them an alternative perspective on how Native American cultures and history are woven into the history of the United States. As one student noted: “It was interesting to see more examples of Native American culture, from a Native standpoint, as until then the unit had only focused on their culture as dealt with by the Corps. For example, the gallery of Native pottery and equipment showed their knowledge of the land around them and how they could use it to their advantage.” Students came away with a deeper understanding of the contributions of Indigenous peoples to the Corps of Discovery’s success.

Remington’s painting, Shotgun Hospitality, encouraged students to step into another’s shoes in describing the encounter. One student wrote from the trader’s point of view:

“As I’m traveling up north to get back to camp, it’s starting to get chilly. The frigid breeze brushes the back of my neck, and my teeth start to chatter.

‘This ain’t gonna be an easy journey,’ I whisper to myself.

I hear the cricket’s song in the distance, and everything is at peace, the stars shining brighter than any sun ever could. Right below me, the sound of the wagon wheels turning.”

Another student expressed: “I was reminded in the picture with the people surrounding the fire that there were different points of view, different opinions, and different outcomes during the expedition . . . I thought this exercise was a reminder that even though the Lewis and Clark expedition was a huge success for American citizens, it was a very different experience for the Native Americans.”

Gignoux’s White Mountain Landscape, enabled students to visualize the scope and scale of the expedition. One student remarked, “At the second station with the gorgeous piece of art, the landscape felt so familiar and unknown at the same time. I felt very adventurous [as] Lewis and Clark did.” Another student observed, “I believe that the tour connected greatly towards my understanding of what Lewis and Clark saw when they first looked at the mountains. I took a look at the mountains in the picture and even though they weren’t the Rockies I believe I understood the grandeur of the scenic view ahead of them.”

In response to Yatika Starr Fields’s painting, White Buffalo Calf Women March, students shifted their perspectives on Native Americans. Rather than viewing them as victims they saw them as sovereign agents of their own destinies. As one student reflected, “Native Americans weren’t weak, and they didn’t just surrender everything they had. They fought and they still do. They’re not silent and they won’t go unheard. This was shown in the highway protest painting.” Another student remarked, “Another example, that I personally found extremely interesting, was the painting of the protests over the pipeline . . . I loved the fact that the protest was led by women.”

In our pandemic year, a new group of students was able to experience this tour through three asynchronous videos. Vivian led students through the activities via a taped Zoom experience. Even though we could not visit the museum, students developed greater insights, compassion, and acceptance of others’ perspectives through these lessons.

Reframing the Lewis and Clark expedition to elevate the contributions of Native Americans is in keeping with our district’s push towards equity and multicultural education. This approach has furthermore offered students an opportunity to view Indigenous people in both historical and contemporary contexts. Inspired by our sessions with the Hood Museum, I have reimagined the subsequent unit on the Trail of Tears, which is now entitled, “Indigenous People: Removal and Renewal” and a previous unit on the founding fathers that is now entitled “The Founding Fathers and Slavery: Bringing Forward the Unseen.”

This post was authored by:

Ellen Fisher, Social Studies Teacher, Richmond Middle School

Vivian Ladd, Teaching Specialist, Hood Museum of Art

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Ellen Fisher is a social studies teacher at the Frances C. Richmond Middle School in Hanover, NH. Since first visiting the Hood Museum of Art with students to view the exhibition Native American Art at Dartmouth: Highlights from the Hood Museum of Art in 2011, she has been on a mission to integrate visual art and thinking skills into her American history curriculum. Ellen has participated in several teacher institutes at the Smithsonian American Art Museum, National Gallery, and National Portrait Gallery, and has collaborated extensively with the Hood Museum’s education program. Ellen was named the 2019 New Hampshire State History Teacher of the Year, and recently received an award from the Gilder Lehrman Institute for American History in innovative curriculum design.

Vivian Ladd has been an art museum educator for 30 years, designing and teaching programs as a museum education consultant, and on the staff of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, the Currier Museum of Art, and the Hood Museum of Art. She holds a BA in english from Barnard College, an MA in art history, and has completed her coursework toward a PhD in art history from Boston University. Her work involves supporting the docent program, developing teaching strategies for the galleries, and organizing teacher and adult workshops. She also coordinates programming with the Geisel School of Medicine and collaborates on programming for the Tuck Business School. She has written both online and print publications for adults, children, teachers, students, and families.

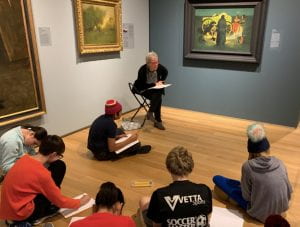

Feature image: K-12 students on a tour of the exhibition Portrait of the Artist as an Indian / Portrait of the Indian as an Artist, on view in Hartevelt Gallery January 26, 2019–February 23, 2020. Photo by Michael Moran.

Comments are closed.