Lick Creek Kin

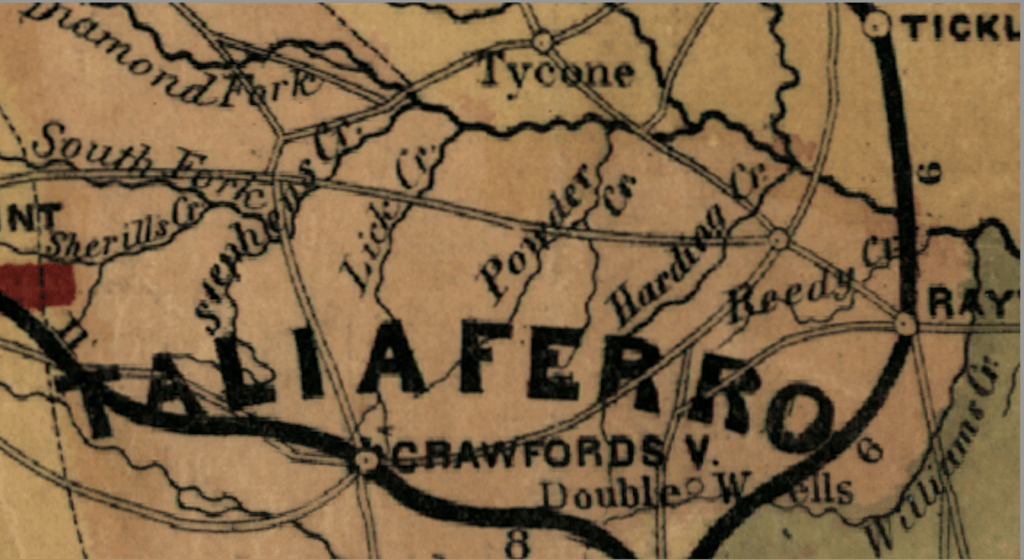

The most deeply rooted histories in the project involve a ruptured family. Father Ben, wife Julia, and children Mima and Bob were among the seven persons enslaved by Andrew Stephens upon his death in 1826. They were parceled out as a sort of human patrimony among Stephens’ five orphans and their guardians, who resided in Upsom, Taliaferro, and Troup counties. Julia soon vanished from the record but the father, son, and daughter continued for years to be discussed in letters exchanged between free white brothers Alexander, John Lindsay, and Linton Stephens.

By the 1850s, father Ben Stephens and son Bob Stephens returned to the site of their Taliaferro County captivity, and as they grew older at this locale, they kept using the last name of their former enslaver. They seem to have made what the white Stephenses dubbed “the Plantation” or “the homestead” into a their own source of deep solace. The farm on a slight elevation over Lick Creek contained a cemetery where roughly a dozen white Stephens were laid to rest. It was also where between 1857 and his 1876 death, Ben became the figure of “grandfather” to dozens of people, only a select number of whom were blood kin.

On this modestly-sized working farm, several extended enslaved families witnessed the transition from bondage to freedom. Bob Stephens bore three children with a woman named Betsy (or Elizabeth in several legal documents), who had already parented four children with another enslaved man named William. (In due time, our project will be including family trees and other diagrams of connection that will schematize those relations). The oldest of Betsy’s offspring was a man named John, who absented himself from the county during the Civil War and then in 1865 married Netty, a freed woman who had been among those Hancock resident enslaved by Linton. The couple moved to Savannah, back near the lowcountry where Netty had likely been raised. They wrote letters to Taliaferro and did their best to stay in touch with what became a four-generation kin community at the heart of a world on the Stephens’s farms.

Others residents of the Lick Creek tracts (subdivided into parcels after emancipation) included the families of Vincent Stephens, Fountain Stephens, and Travis Stephens. They and their children weathered sickness and death in the early years after slavery within a short walk of the Little River tributary. As freed people, they farmed the land that they had once tilled as slaves as the bright prospects of freedom in the late 1860s slowly dimmed. In the 1930s, Georgia Baker recollected how she spent her youth at this locale for a WPA interviewer in Athens. An elderly woman at that point, Baker recalled with some warmth the neighborhood where “all of us was kin to one another.”

IMAGE CREDIT: detail from Lloyd’s Topographical Map of Georgia (New York, 1864) Library of Congress.