The Shackled and Freed of Hancock County

The gangs of enslaved workers driven into the cotton fields around Sparta, Georgia generated enormous wealth for Hancock County planters. It was not uncommon for a hundred or more slaves to be owned by the most self-confident elite of this Middle Georgia locale.

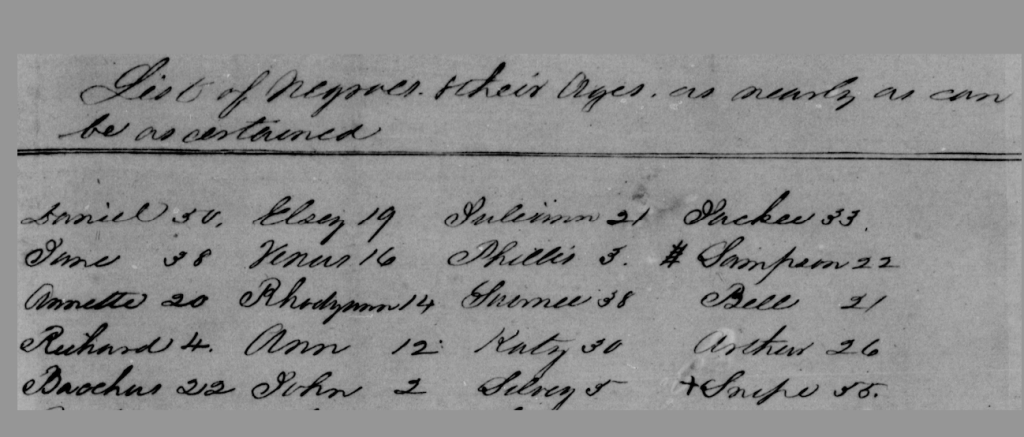

Linton Stephens, an ambitious lawyer with an impressive educational pedigree, joined this rarified status of power and prestige in 1852, when he married a widow named Emmeline Bell. His exchange of wedding vows instantly brought nearly 50 Black Georgians under his absolute authority. Within a year, he tapped his new wife’s financial resources to more than double his holdings. In his single largest acquisition, he forcibly moved two dozen enslaved families from the lowcountry rice kingdom to his expanding Hancock County properties.

Within a year of this relocation, a group of Linton’s lowcountry captives fled their new home, only to be recaptured a few months later. The entire group suffered an especially grinding form of bondage and suffered bouts of physical punishment regularly noted in their new master’s correspondence. Within the Sparta mansion, Linton and Emmeline expected a core group of slaves to attend to their needs and those of their baby girls. Physical punishment was the consequence when such intimate duties were neglected. Emmeline Bell’s 1857 death cast a shadow over the household and significantly worsened Linton’s flaring temper and recourse to violence.

Slavery ended with greater drama in Hancock County than in neighboring Taliaferro. Late in 1863, dozens of Black men sought to make common cause with the invading United States army. Two leaders of this squashed attempt were executed; most others received brutal but not fatal sentences of hundreds of lashes. Other conspirators, including a favored dependent of Linton Stephens’ father-in-law, survived that ordeal to become state lawmakers during Reconstruction’s brief period of Black political ascendancy.

Post-Civil War ties between freed people and their former Hancock County enslavers took many forms. Biracial offspring of wealthy fathers have been brought to light by several historians already. The case of Amanda American Dickinson, the country’s richest Black woman of the post-war period, is especially well-known. Her legal suit had a counterpart in the attempt of the Augusta-based Belcher family to seek the legal services of Alexander Stephens. That story that is laid out in documents collected in our project. The Belcher suit, unlike that of Dickinson, failed to recapture a once-promised patrimony.

Both antagonism and accommodation are evident in documents that chart slavery’s aftermath in Hancock’s cotton-rich domain. The Black lives in the greater Sparta area are not as well-developed in the Stephens papers as those of the Taliaferro characters. One notable exception concerns the case of Linton Stephens Ingram, a protege of the Stephens’ brothers. After attending Atlanta University (alongside two children of Harry and Eliza), Ingram played a leading role in Hancock’s establishment of its own institution of African-American higher education.

IMAGE CREDIT: Detail from tally of slaves sold to Linton Stephens in 1852; Alexander H. Stephens Papers, Library of Congress.