Before I begin the Historical Background for Multi-Quire Codices, you may find a few other pages to be useful in learning how to make single-quire codices, multi-quire codices, and parchment.

Multi-quire codices emerged from single-quire codices. A single quire codex takes the form of what we consider today as a traditional book. To learn more about the single-quire codex and codices in general take a look at this page:

This link will give you the necessary steps to construct your own multi-quire codex:

How to make a multi-quire codex

This link will provide information on the parchment making process:

Here, I will discuss the historical and cultural background information that laid the foundation for the multi-quire codex to emerge.

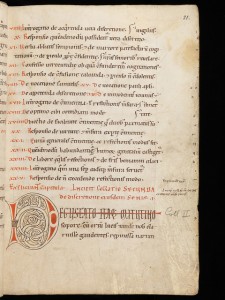

The development and implementation of the multi-quire codex came as a result of cultural changes occurring throughout Europe and the necessity for documenting religious texts beginning with the 1st - 4th centuries AD. The first shift that laid the foundation for the emergence of multi-quire codices was the transition from papyrus to parchment. Though there were papyrus codices for the first few hundred years of the codex form, parchment eventually overtook papyrus beginning in the 4th century AD. From this initial change in book material, parchment codex gained popularity with the Christian church that utilized first in monasteries. From this point on we see efforts of standardization of scripts and literature, one of the first being Charlemagne. The constant revival of literacy and transcribing that consumed this period are the primary sources of the surviving manuscripts and texts we possess today.

Page from a parchment codex