Next in our series of interviews with Digital Library Program staff. Today, Anthony Helm, Head of Digital Media and Library Technologies, answers questions about his work.

What does the Head of Digital Media and Library Technologies do?

I manage two departments within the Library, the Jones Media Center and the Digital Library Technologies Group. While both have a technology focus, they are almost like yin and yang. The JMC is a patron-focused service location where creative output is consumed and produced. The DLTG is responsible for managing the Library’s information technology infrastructure, including our integrated library system (Innovative Interfaces’s Sierra product) and the myriad applications that deliver our content online. (We do, also, use some services provided by campus ITS, including their virtual machine hardware to host our servers and OmniUpdate for many static web pages).

How did you get here? That is, what was your path to becoming the Head of Digital Media and Library Technologies here at Dartmouth?

I used to describe it as a dervish of a dance, constantly changing partners between teaching positions and technology positions until I gradually learned how to find them both in a single place. My educational background is in television and radio production (undergrad) and Japanese language, literature, and culture (master’s). I’ve been an English teacher, a BBS operator, a visiting Japanese instructor, an escaped Buddhist novitiate, a computer lab manager, a small campus IT director, and an academic technologist. In 2008, I eventually arrived at Dartmouth to head the Arts & Humanities Resource Center, before landing in my present position three years after that.

What’s a notable (interesting, challenging, unusual) project that you’ve worked on recently?

In the JMC, last year we completed a major renovation of the Center, which was the culmination of years of planning, and it has turned out incredibly well. We are, however, still learning and exploring what we can do in the new space and discovering new opportunities for faculty and students to be creative. We may even try to produce a small multimedia play in our “Innovation Studio” space.

On the DLTG side, we are actively working to build an academic repository of scholarly content as well as to enhance the capabilities of our library digital collections repository infrastructure. I’m very excited about both of these. That said, there seems to be no end to what we learn about other people’s workflows.

What do you wish that more people knew about digital media and library technologies (in relation to the Digital Library Program or not)?

In the Jones Media Center, we provide access to the creative output of thousands, if not millions, of people in the form of an audio and video collection of over 30,000 DVD, videos, videogames, CDs, CD-ROMs, as well as board and card games. We also enable people to become creators of their own multimedia-based essays and stories, by loaning a wide array of video cameras, still cameras, audio recorders, microphones, lights, projectors, and much more.

At the same time, we are fighting an uphill battle to make sure that all of this content will remain accessible for future generations. That’s where the work of DLTG and our entire Digital Library Program team comes into play. There is a neverending amount of work to be done. Though budgets in higher ed are constrained, this is a vital growth area, and it is endlessly fascinating to be a part of it.

Who are you when you’re not being the Head of Digital Media and Library Technologies?

I am an a capella singer, an actor and director of community theater, and a (casual these days) video gamer.

What has been a notable challenge with a DLP project? (question from Lizzie)

With a book, when it is published, that’s pretty much it. It is self-contained and can sit on a shelf for years. A contemporary DLP project is not as simple as scanning the pages of a book and putting up a PDF or JPEG images online. A really good DLP project feels more like a film by comparison. There is so much that so many people have to plan and develop and do to deliver the final output. But more than that, the final output must be continually monitored and evaluated to ensure that it continues to be accessible. An operating system update or a browser update can change everything. A good amount of the effort put into creating a DLP project is spent designing a system that can be accessed and adapted by future developers and librarians. That’s one reason we tend to favor open standards and open source development tools.

What question would you like another member of the Digital Library Program staff to answer?

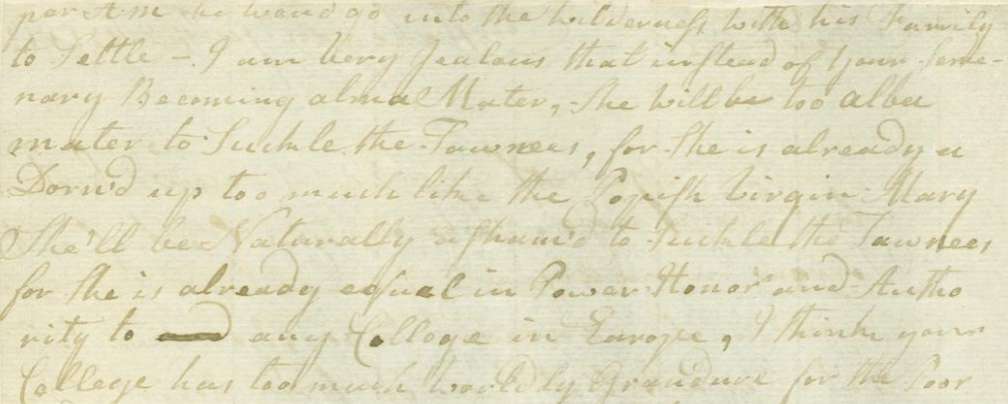

Is there a Library collection or a period of Dartmouth history you’d like to see digitized and available to the world?