With this post, we inaugurate a series of interviews with Digital Library Program staff. Today, Jenny Mullins, Digital Preservation Librarian, answers questions about her work.

What does a Digital Preservation Librarian do?

Fundamentally, a Digital Preservation Librarian ensures that digital materials created or acquired by the Library remain usable over time. And by “usable” I mean they must be accessible, understandable, and authentic. Our access to digital materials is mediated through software and hardware, which are constantly evolving and/or becoming obsolete. As Digital Preservation Librarian, I try to mitigate the risk posed by evolving technologies by instituting policies and workflows to actively manage files over time. I advocate for the use of open, well-supported file formats, monitor the viability of file formats in our collections, and check the fixity of files to protect against bit rot. I also work with metadata (and Metadata Librarians) quite a bit. If we have a file, but we can’t find it, identify it, or contextualize it, it’s not going to be very usable.

In addition to establishing best practices within the Library, I’ve also been trying to reach out to creators of digital content — which at this point is pretty much everyone — and help them understand how to best manage digital assets. Digital preservation starts at the beginning of a file’s life cycle, and requires ongoing active management. The more that researchers understand about how to care for their digital materials, the better, especially if these materials have a chance of ending up in library or archival collections.

How did you get here? That is, what was your path to becoming the Digital Preservation Librarian here at Dartmouth?

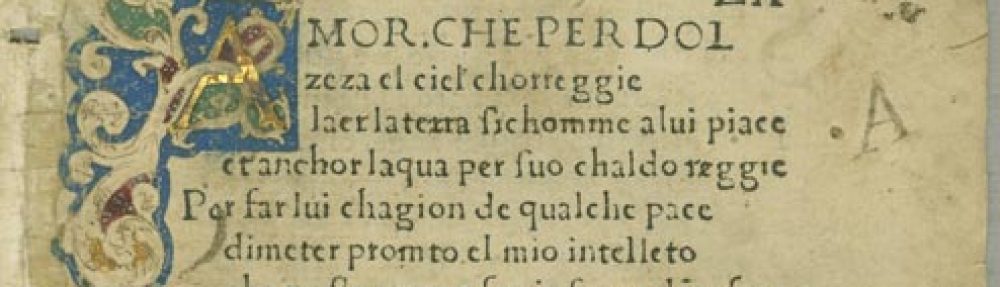

It was a long and winding path. I started my library career hoping to be a book conservator. I worked in conservation labs as a technician, and focused my MLIS in Preservation Management. My life took some twists and turns, and I randomly happened into (literally as a result of a conversation with a stranger on a bus) a three-month internship at the Bay Area Video Coalition helping to build a digital repository for dance video. I knew nothing about video, and almost nothing about digital preservation, but was able to apply the preservation fundamentals I had learned in school and through working with book and paper collections. As I started working with these new-to-me formats, I kept asking myself questions like “How is this video file different from a book? How is it the same? What does this say about the kinds of questions we should ask or decisions we should make?” Slowly, through lots of research, practice and the help of colleagues like Lauren Sorensen and Dave Rice, I developed a pretty good understanding of digital preservation fundamentals. I remember being at a Digital Preservation Interest Group meeting at ALA about a year after I started that internship (which turned into a full-time job) and realizing, “I finally understand what everyone is talking about!” I felt like I’d climbed up a pretty steep hill and could finally see the surrounding landscape. A month later, I submitted my application for the Digital Preservation Librarian position here at Dartmouth.

What’s a notable (interesting, challenging, favorite) project that you’ve worked on recently?

I’m working on developing a mini-workshop with Caitlin Birch on designing Oral History projects with long-term preservation and archiving in mind. I’ve been really trying to get into doing more outreach, but it’s not one of my natural strengths. Working with Caitlin has been a great learning experience — she’s great at engaging an audience and explaining complicated ideas in a way that’s easy to digest.

What do you wish that more people knew about digital preservation?

In the context of the Library, I’d like people to understand that preservation of digital materials is deeply collaborative — success relies on the expertise of many individuals from multiple departments. My role is often to get the right people in the room talking to one another.

Who are you when you’re not being the Digital Preservation Librarian?

For the next few months, I’m Interim Head of the Preservation Department, so I get to think more broadly about the preservation needs of the Library. After 5pm and on weekends, I head back to my house in the woods in small-town Vermont.

What question would you like another member of the Digital Library Program staff to answer?

“What’s your favorite DLP project and why?”