Hello World! This post inaugurates the Dartmouth Digital Library Program’s new blog, in which we’ll announce new digital collections, highlight interesting items, and explore the people and processes of our Digital Library Program. Please check back often to see what’s new and what’s cool.

This weekend, Dartmouth College will co-host with the Society of Early Americanists a symposium on Indigenous Archives in the Digital Age. The event celebrates The Occom Circle, a digital edition of the papers of Samson Occom (1723-1792), a Mohegan Indian who was instrumental in Dartmouth’s founding. The Occom Circle is one of the Dartmouth Digital Library Program’s largest projects to date, involving librarians, archivists, technologists, scholars, students, and members of the Mohegan tribe.

Over the past few years, I have been lucky to work with my colleagues on The Occom Circle. Doing document transcription, simplified “mark-down,” and TEI markup was a hands-on way to learn about a digital humanities project from the ground up. (For more details, see the chapter that several team members wrote for the collection Digital Humanities in the Library). I also found that I just liked Samson Occom. His words were fascinating, although alien to the extent that he was writing within a profoundly different historical, cultural, and religious context. His journal entries were comforting in their repetition; every morning, it seemed, began with him waking, breakfasting, and setting off on his horse (if he was fortunate to have one) or on foot (more often than not) to the next settlement to preach “to a large number of people.” And yet there were moments of epiphany, of joy and sorrow, that broke through the daily tedium: Occom officiated at a wedding, or comforted the sick and dying, or went fishing with his sons, or rejoiced in the kindness and compassion of his hosts.

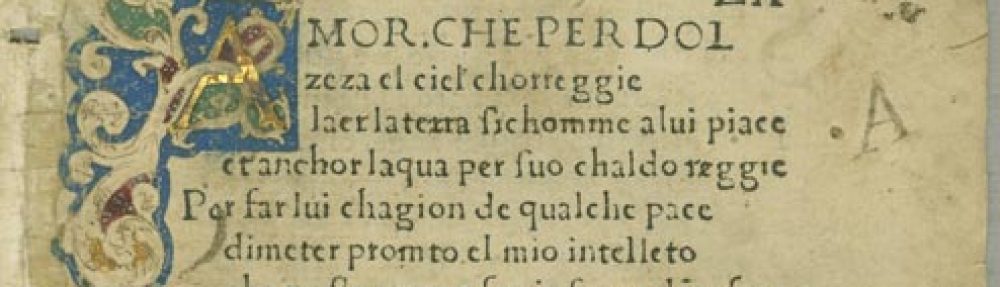

For an exhibit at Dartmouth’s Rauner Special Collections Library in conjunction with the conference, we wanted to explore Occom’s role in a series of events related to the founding of Dartmouth College. In 1765, Eleazar Wheelock, wanting to raise funds for his project of converting Native Americans to Christianity at his school in Connecticut, sent Occom, who was already an ordained minister, to Great Britain. There, Occom became a celebrity, preaching to numerous congregations, meeting religious leaders like George Whitefield (one of the founders of Methodism) and political figures like William Legge, 2nd Earl of Dartmouth (for whom Wheelock would eventually name his fledgling institution). Occom’s return to the colonies, however, precipitated his break with Wheelock. He discovered that his family had been neglected, and that his mentor planned to move the school to the New Hampshire frontier.

Some years later, Occom wrote a scathing letter berating Wheelock for abandoning his intention to teach Indian youth in favor of creating a College. He felt like Wheelock’s “Gazing Stock, Yea Ever a Laughing Stock, in Strange Countries, to Promote your Cause.” Other mentors, such as Whitefield, Occom noted, had warned him that he was nothing but a tool that would be used and set aside. Even in the heat of passion, Occom did not forget his schooling. He threw the learning Wheelock had given him back in his face. He wrote:

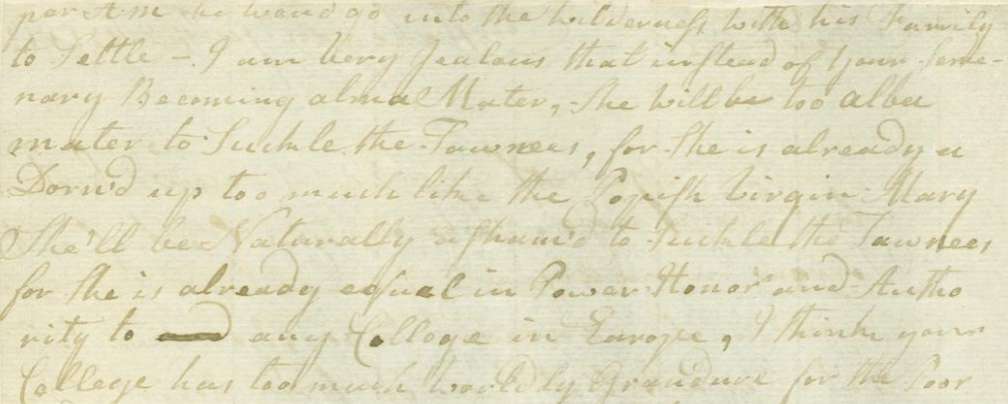

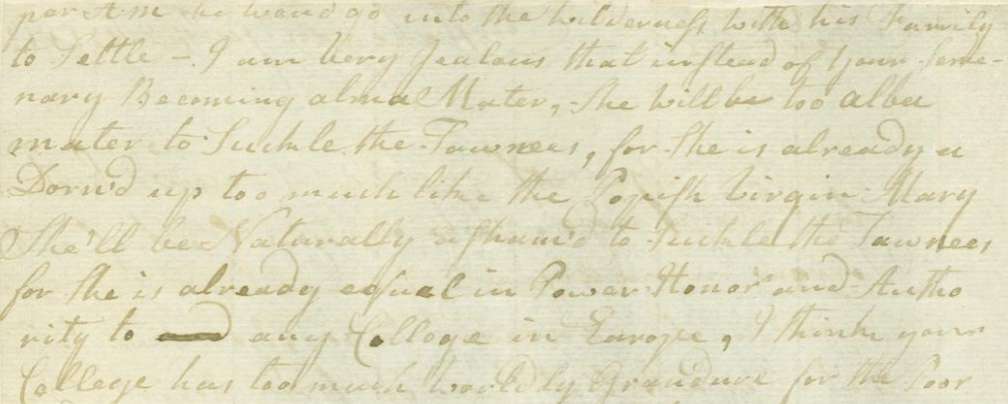

I am very Jealous that instead of your Semenary Becoming alma Mater, She will be too alba mater to Suckle the Tawnees, for She is already a Dorn’d up too much like the Popish Virgin Mary She’ll be Naturally ashame’d to Suckle the Tawnees for She is already equal in Power, Honor, and Authority to and any College in Europe.

With alba mater (in Latin, “white mother”), Occom puns on alma mater (“foster mother”), a traditional metaphor for a college.

Excerpt of letter from Occom to Wheelock, July 24, 1771

This was an extraordinary moment in the story of Dartmouth’s founding. Occom recognized the failure of the institutions and people who nurtured him to uphold the values which he had been taught. Archives have always contained marginalized voices; digital archives amplify those voices to help fill the silences of history, and to remind us of our communities’ ideals. During the celebration of its 250th anniversary, Dartmouth will certainly reflect on its struggle to embrace the original commitment to Native education for which Occom worked so hard, and which we can see evidence of in the documents of The Occom Circle.

The Occom Circle includes digital editions both of Occom’s journal of his trip to Great Britain and of his final letter to Wheelock. The journal and the letter themselves, along with many other related documents, are in the exhibit “Power, Honor, and Authority: Samson Occom and the Founding of Dartmouth College.” The exhibit was curated by Laura Braunstein and Peter Carini, and will be on view in Rauner Library’s Class of ‘65 Gallery until October 28, 2016.