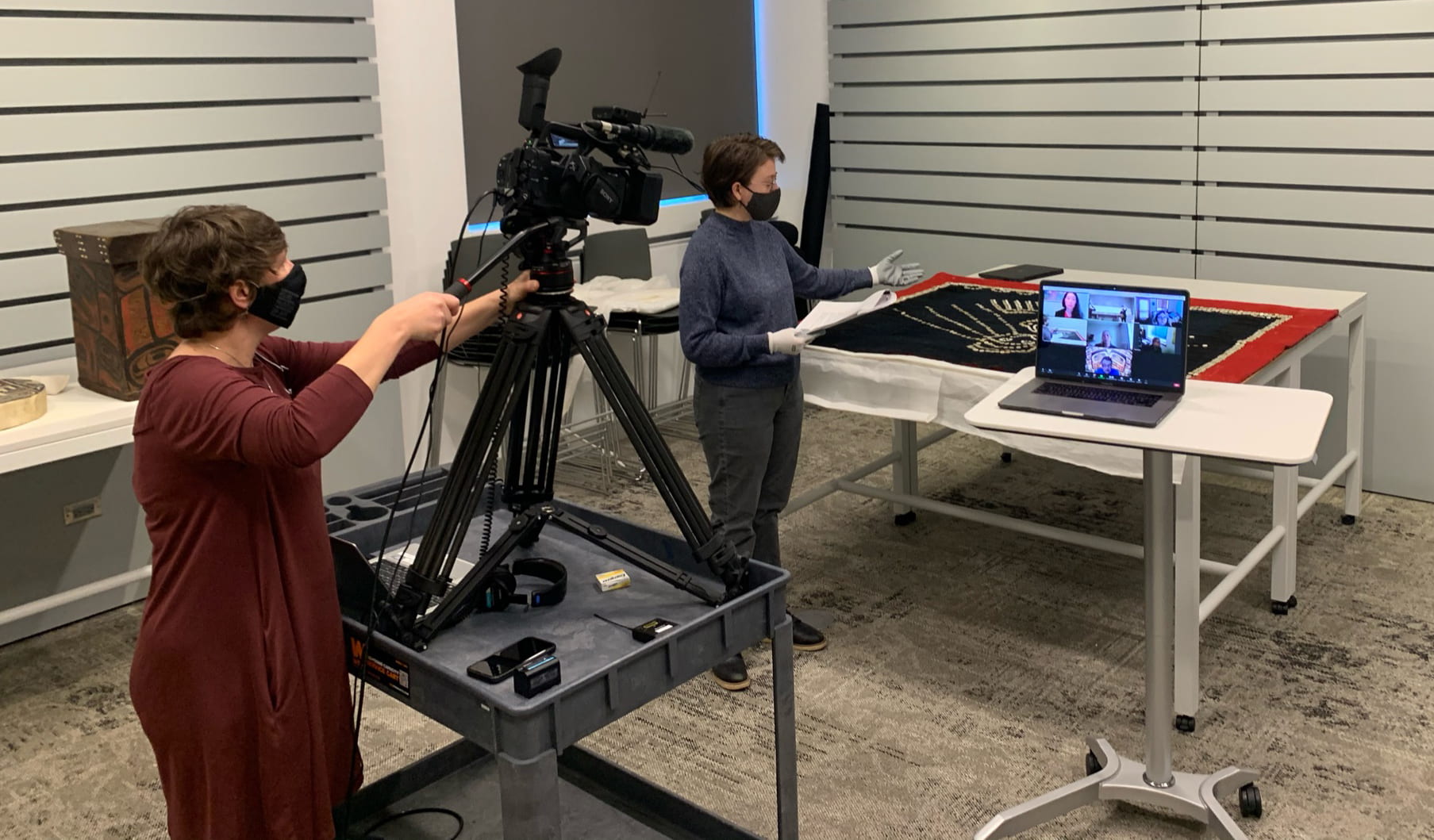

In January 2021, Dr. Rosita Worl, president of the Sealaska Heritage Institute, invited the Hood Museum of Art to a virtual visit with her organization. Based in Juneau, the Sealaska Heritage Institute (SHI) perpetuates and enhances the Indigenous cultures of Southeast Alaska. In keeping with their goals to promote cultural diversity and cross-cultural understanding, the SHI staff organized this visit around 24 objects created by Tlingit, Haida, and Tsimshian artists that currently live in the Hood Museum of Art’s collection. During the visit, SHI staff shared their cultural and professional expertise with us. It was a harmonious start to our partnership, and enjoyed by Hood Museum staff members, which included me, Dr. Jami Powell, curator of Indigenous art; Sue Achenbach, museum preparator; and Kait Armstrong, Bernstein center for object study assistant.

Due to the ongoing global health crisis and consequent travel restrictions, our colleagues were unable to visit us in-person at the museum to see the Hood’s Tlingit, Haida, and Tsimshian collections. However, several of the objects we visited in the virtual format were not new to Dr. Worl nor Dr. Chuck Smythe, the history and culture director at SHI. During Dartmouth’s 2019 Commencement ceremony, they traveled to campus for the graduation of Miranda Worl, Rosita Worl’s granddaughter. At this time, they stopped by the newly renovated Hood Museum where they saw several Tlingit pieces on view in Native Ecologies: Recycle, Resist, Protect, and Sustain, an exhibition curated by Rayna Green around the idea of Native relationships with and responsibilities to place, land, water, plants, animals, and family.

One of the objects most admired by Worl and Smythe, both in the Hood gallery and, later, during the virtual visit, was the feast dish carved from alder wood and inlaid with seal bone and abalone shell by a Tlingit artist sometime before 1905. Finely crafted and in remarkable condition, the feast dish depicts sea lion crest imagery indicative of the Sitka-based style. With this object, and several others, SHI staff members were able to work with us during our virtual meeting in the Bernstein Center for Object Study to identify, correct, and bolster catalog information. For example, Smythe –– in his signature jovial style –– pointed out that this stunning object is not an “oil dish” or simply a tool for “food service” as was indicated on our website record. Rather, it is a feast dish which was most likely created to be used during potlatch or in Lingít, a ku.éex’, an elaborate ceremony of feasting and gift exchange.

Throughout the virtual visit, it became clear to all of us at the museum that these objects were not simply beautiful or purely aesthetic. As the SHI staff members shared with us, objects like the feast dish hold aesthetic, ceremonial, cultural, social, political, and spiritual value. Many of the Tlingit, Haida, and Tsimshian objects in the Hood’s collection have spirits and cultural significance that we as outsiders to the community cannot fully understand. Yet, as museum staff, it is our responsibility to be stewards for these at.óow — prized possessions of clans often marked by specific crest designs — and all historic Indigenous art that lives in our collections. Our stewardship is important and must be grounded in the knowledge that some of these objects were never meant to leave their Indigenous communities (see the work of Sabena Allen, Class of 2020, and former Hood Museum intern). To quote the powerful and nuanced statement of Dr. Worl, “I am mad that collectors took all of our things, but I am sure glad that museums took care of them.”

Taking care of these objects in the Hood Museum’s collection means that we must honor all of their complexities, cultural value, and the artists who made them. Museum records may not identify all of these Tlingit, Haida, and Tsimshian artists, but they would have been, and in many cases continue to be, well known in their communities. How can we as museum staff do this important work? We rely on cultural experts like Dr. Rosita Worl, Dr. Chuck Smythe, and other folks at the Sealaska Heritage Institute. We prioritize the Indigenous knowledges and interpretations of their Council of Traditional Scholars. We change our cataloguing systems to reflect these knowledges and we build community access around these objects and their records. We act with reciprocity by sharing with Sealaska Heritage Institute, and the communities they work with, opportunities for collaboration. These include long-term loans, participation in their War and Peace Online Exhibit, curated by Kaila Cogdill and directed by Chuck Smythe and Rosita Worl, 3-D photogrammetry of objects useful to their artists, and repatriation of objects whose clans wish to see their return.

Above all, I am deeply thankful for this partnership between the Hood Museum of Art and the Sealaska Heritage Institute. It is incredibly generous of SHI to offer us their time and expertise even as they are in the middle of a community-wide and formidable effort to “make Juneau the Northwest Coast arts capital of the world.” I am looking forward to learning more from the SHI colleagues we visited, including Kathy Dye, Kari Groven, and Amy Fletcher. Next time, I hope to have the opportunity to meet with Alaskan Native staff members and artists, who were not able to attend this virtual visit. Meanwhile, Hood Museum staff will work to re-interpret and better steward these Indigenous objects from Southeast Alaska.

As we continue to craft this partnership, perhaps some of the objects we visited virtually can make their way home in time for Celebration 2022: Celebrating 10,000 Years of Cultural Survival. Hosted by Sealaska Heritage Institute in Juneau since 1982, Celebration is one of the largest gatherings of Southeast Alaska Native peoples. Particularly after the cancellation of the 2020 in-person celebration, there will be much to rejoice when we can finally meet face to face in 2022. Even though we were only able to connect virtually, we continue to move forward and improve the stewardship of these objects.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Taylor Rose Payer joined the Hood in September 2020 as the Cultural Heritage and Indigenous Knowledges Fellow. Taylor assists with developing relationships between the Hood Museum of Art, Dartmouth College Library, and Native American and Indigenous communities built around collaborative and collections-based research. She earned her M.A. in public humanities from Brown University and B.A. from Dartmouth. Taylor is a member of the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa.

ABOUT THE SEALASKA HERITAGE INSTITUTE

Sealaska Heritage Institute is a private nonprofit founded in 1980 to perpetuate and enhance Tlingit, Haida and Tsimshian cultures of Southeast Alaska. Its goal is to promote cultural diversity and cross-cultural understanding through public services and events. Sealaska Heritage also conducts scientific, and public policy research that promotes Alaska Native arts, cultures, history and education statewide. The institute is governed by a Board of Trustees and guided by a Council of Traditional Scholars, a Native Artist Committee and a Southeast Regional Language Committee. Click here to learn more.

Comments are closed.