“So . . . um . . . is the Kusama currently on view?” I asked (blurted out to) my new colleagues during our first tour of the Hood Museum of Art, my cheeks flushed, my face kawaii.

I had just started a fellowship in the registration and collections department at the Hood. When I was interviewing for the job, I returned to the museum’s website many times to try to absorb as much information as possible. As an admirer of Yayoi Kusama and her work, I was excited to discover that one of her early soft-sculpture pieces, Accumulation II, is part of the Hood Museum’s collection.

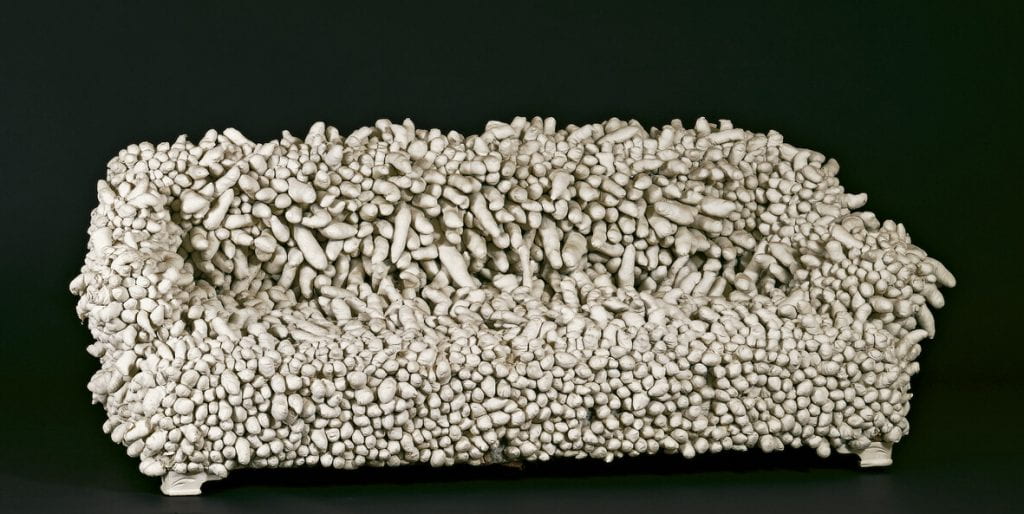

You may have experienced some of Yayoi Kusama’s work yourself. Perhaps through a painstakingly short 45 seconds in one of her Infinity Rooms, or by gazing upon one of her larger-than-life polka-dotted pumpkin sculptures, or by resisting the urge to let your eyes un-focus as you cast them across a dizzying Infinity Net painting. Maybe you’ve even seen Accumulation II for yourself at one of the Hood’s previous exhibitions and felt the tension of a supposedly soft furniture piece completely rejecting its original utilitarian purpose. (The answer to my question at the beginning of this piece was “no,” so I can only speculate as to what that’s like.)

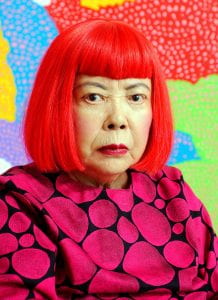

Kusama, also known as the “Princess of Polka Dots,” is one of the most well-known living artists in the world and has had a tremendous influence on contemporary art and pop culture. However, her current level of popularity comes relatively late in her career. As a Japanese, female artist living with mental illnesses, she struggled for decades to gain recognition for her art and was often overshadowed by her white-male peers.

Kusama began creating Accumulations in her New York City studio in 1962. They typically consisted of domestic household objects—an armchair, a suitcase, women’s clothes and shoes—covered entirely in stuffed, sewn fabric phalluses and dried macaroni. These works were exhibited alongside her Infinity Net paintings at her breakthrough Driving Image Show at the Castellane Gallery in New York City in 1964, the first of her immersive environment shows. Accumulation I and II were later included in Kusama’s Floor Show in 1965, which also featured her first Infinity Room installation: Infinity Mirror Room – Phalli’s Field. This all came only 7 years after Kusama relocated to New York City from her hometown in the Nagano Prefecture of Japan without any prior connections to the New York City art scene.

Following these shows, Kusama was often quoted in interviews describing her Accumulation sculptures as a form of self-therapy, a way to help process psychosexual fears and obsessions. But as Alexandra Munroe writes in Obsession, Fantasy, and Outrage: The Art of Yayoi Kusama:

“Through art, her violent possession and control over not one but thousands of penises represent perhaps a victory, the freedom from subjugation, from dependency and the glorious right to dominate back.”

Kusama is not just coping with her experiences, she’s actively subverting the power structures she faced in her daily reality. Her early work during this time demonstrates her acute awareness of her critics’ and the public’s perceptions of her as an outsider artist. Using spectacle to exploit these perceptions, Yayoi Kusama gained even further recognition for her art and her influence in New York art circles.

In her autobiography, Yayoi Kusama writes her work “always asserted itself by shocking the viewer.” It is perhaps this assertiveness that continues to draw me to her work. Since the beginning of her career, Kusama has refused to be interpreted through a single lens—not just kitsch, or avant-garde, or pop. And as a mixed-race Japanese American woman, I can’t help but look for kinship in her art and draw inspiration from her determination.

At the time I was writing this post, Kusama had just celebrated her 93rd birthday. She lives and works in Tokyo, where she is still creating art in her studio. While I can’t travel back in time to live the full experience of Kusama’s iconic 1960s era, I can quietly wait for Accumulation II to leave off-site storage and see the light of day once again. Maybe even sometime before October 2024, which happens to be when my fellowship ends.

This post was authored by:

Nichelle Gaumont, Hood Museum Board of Advisors Mutual Learning Fellow

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Nichelle Gaumont is the 2021–24 Mutual Learning Fellow in Registration and Collections. Prior to joining the Hood Museum, Nichelle served in an Americorps position with St. Paul Public Library in Minnesota, where she focused on increasing technology access and building digital literacy skills in local communities. She collaborated with non-profit Literacy Minnesota to research digital access in Minnesota’s counties and contribute to a needs assessment report for the MN Dept of Education. She also served in an Americorps position with the George W Carver Museum in Austin, Texas, where she facilitated virtual arts and science workshops for Austin youth. Nichelle graduated from the University of Portland with a BA in psychology and a minor in communications.

Comments are closed.