As a Mutual Learning Fellow in the Curatorial Department, one of the opportunities I have is to research and recommend acquisitions to the curatorial team. In keeping with the spirit of the fellowship—which encapsulates “learning by doing”—I dove right into the task of suggesting my first acquisition in support of Yliana Beck’s A Space for Dialogue exhibition, A DREAM Deferred: Undocumented Immigrants and the American Dream, which explores works of art that call attention to the livelihoods of, and dangers facing, undocumented immigrants in the United States. The first thing I did was research what works we had in the collection that dealt with these topics, and with that, came to understand some of the gaps in our collecting. While the museum has a phenomenal portfolio of prints from the Migration Now series, which called attention to the immigration crisis from allies in solidarity with the immigrant rights movement, the portfolio’s scope was limited in its inclusion of undocumented artists.

In having works that mostly represent non-undocumented allies talking about issues on migration, we are perpetuating the practices of rendering undocumented artists invisible, secluding them to shadow spaces. Undocumented artists have been creating and fighting to imagine and create spaces for themselves, while navigating institutional barriers that prevent them often from applying for grants, accessing funds for art making, attending art school, and engaging in other activities other artists may take for granted. Many undocumented artists have been creating graphics and posters in protest of exclusionary immigration policies and border state imperialism, while simultaneously building on a large legacy of graphics that extend across various movements—from Chicanx Art Movement to the 1980s Artist Call for Solidarity in Central America.

As a person who is queer and undocumented, my curatorial practice is deeply rooted in my own experiences and my own desires: I want to see museums exhibit the works of queer, undocumented, Black and Indigenous artists and artists of color. I want to see multifaceted conversations and visions of the future that we as fugitives of the state are imagining and manifesting for a world beyond borders through art practices; I want celebrations of rest and joy and spaces for healing. Thus, in thinking about the type of artwork I want to acquire for the Hood Museum’s collection, I approach it with a lot of care and intention, as well as a goal to disrupt existing museum practices.

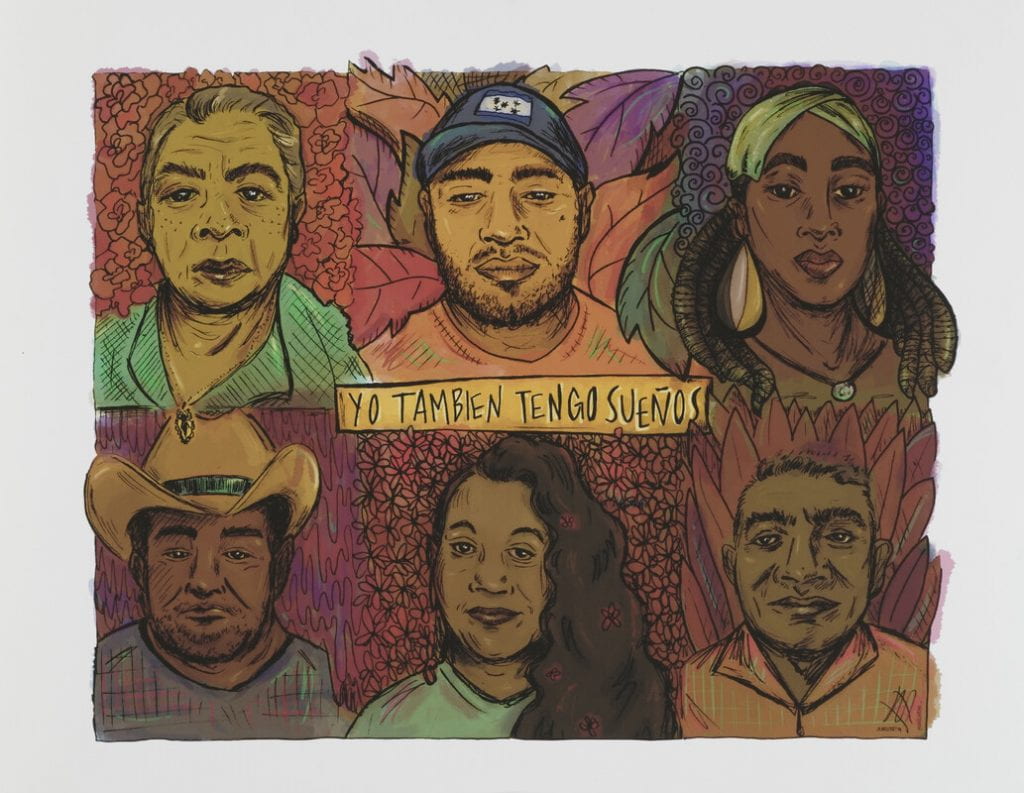

Who is centered in this artwork? How does this work disrupt dominant narratives? What portals or conversations can this art and artist open with their work? Such questions guided me as I learned of the work of Karla Rosas, who also goes by Karlinche, an undocumented and queer artist from Mexico who grew up in rural Southeastern Louisiana and is now based in New Orleans. Rosas is a recipient of the Define American Artist Fellowship, and I was instantly captivated by their vibrant use of colors in their work and the assertion of agency and power through their graphics. I personally gravitated to their piece Yo Tambien Tengo Suenos because it de-centers the Dreamer narrative (which tends to center young, able-bodied student immigrants) and reminds us that the immigrant movement should be inclusive of everyone, regardless of age, gender, sexual orientation, ability/disability, race, educational background, or other factors. By asserting, Yo Tambien Tengo Suenos, or “I too have dreams,” the piece utilizes the power of language to make both a reminder and a demand. The colorful background behind each person represented in this print also invokes vibrant ideas of dreaming and world-building.

Similarly, in Beyond Borders, Rosas invites us to dream of a world without borders. This piece centers the agency, imagination, power, and resistance of undocumented queer, Black, Indigenous, and people of color and asserts our collective ability to transcend political borders. The imposed border is intrinsically tied to the legacy of imperialism, colonialism, dispossession, capitalism, racism, homophobia, and structural inequality. Therefore, when Rosas asserts that we can dream of a world beyond borders, they are making a powerful invocation to not only imagine, but to create a world in which these systems of dispossession and oppression are dismantled.

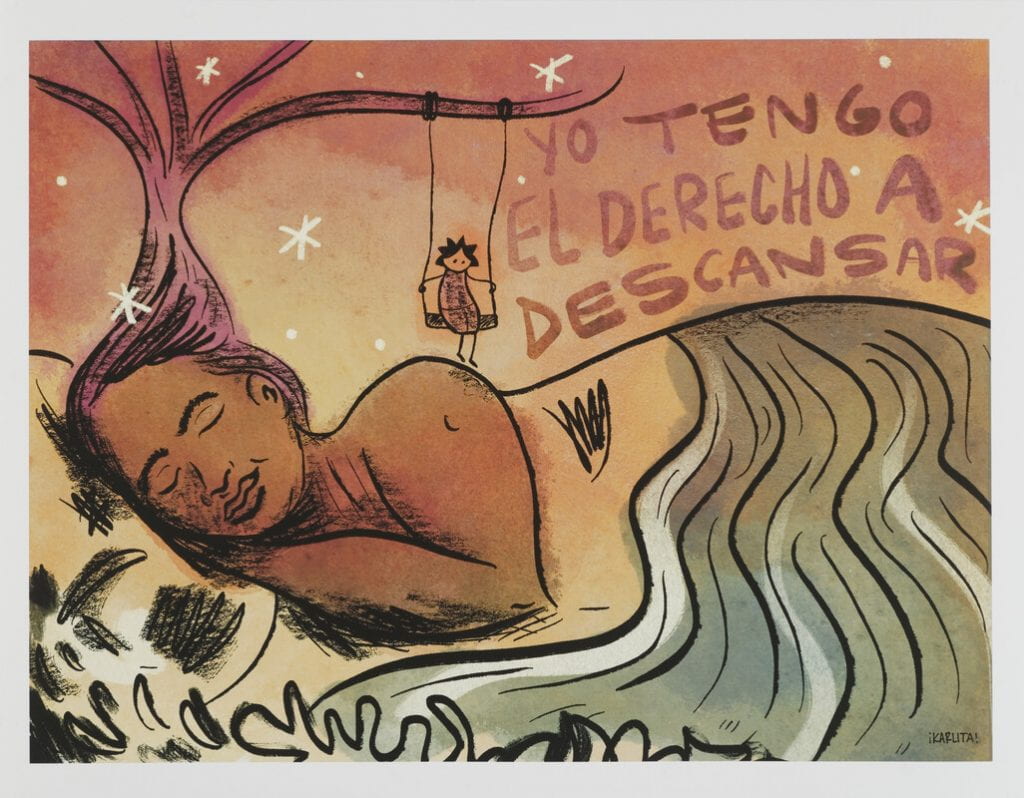

Another work acquired for the Hood was El Derecho a Descansar, The Right to Rest, about which Rosas writes:

“When we allow our bodies to rest, we give ourselves space to imagine, to recharge, observe, sleep, dream. The right to rest is not a luxury but a

fundamental and necessary part of what it means

to be human.”

Rosas borrows the phrase Yo Tengo El Derecho a Descansar from the Indigenous women of the Zapatista liberation movement, who advocated, although unsuccessfully, for the right to rest to be included in a Women’s Revolutionary Law.[1] Rosas’s print is also inspired by the work of Black women such as Rachel Cargle, Sonya Renee Taylor, and Tricia Hersey of the Nap Ministry, who have been advocating for our right to rest.[2]

Rosas’s positioning as an undocumented queer artist, whose art practice and organizing is rooted in their experiences growing up in rural Louisiana, reshapes and challenges the narratives within the graphic arts scene and immigration organizing. More specifically, Rosas’s geographic upbringing in the South provides for a more nuanced dialogue about undocumented organizing and artistry that is often eclipsed by a focus on artists from the East and West Coasts. Rosas’s prints build on the legacy of other printmakers and graphic artists such as the Chicano Graphic art movement, who have utilized posters and other graphics as calls to action and protest U.S. imperialism, the carceral state, and unsafe labor conditions, among other issues. As I continue to work at the Hood Museum, I am aware of how one artist alone does not radically change the conversation, but rather opens a portal for further conversations that provide for more complex and disruptive narratives. My work will continue to be guided by the questions I asked myself when I started this acquisition, but also by Rosas’s demand to dream of a different world—and in this case, dream of different museum practices.

This post was authored by: Beatriz Yanes Martinez, Mutual Learning Fellow.

Sources:

1. Belausteguigoitia, Marisa. “Ramona: El Derecho a Descansar.” Debate Feminista 33 (2006): 119–27. http://www.jstor.org/stable/42625458.

2. Hersey, T. The Nap Ministry. Retrieved from https://thenapministry.wordpress.com/

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Beatriz Yanes Martinez is the 2021–24 Hood Museum of Art Mutual Learning Fellow in the Curatorial and Exhibitions Department. Beatriz graduated from Carleton College with a BA in Latin American studies and as a former Mellon Mays Undergraduate Fellow, they have explored the modes of resilience of Central American immigrants, the power of storytelling, the histories of migration and settlement of Central American immigrants in the East Coast. They have collaborated with the CUNY Research Foundation Testimonio’s project, helping collect stories of immigrants impacted by state-led family separation. Her research and creative practice incorporate interdisciplinary elements combining poetry, photography, and storytelling around themes of diasporic resilience and art, queer studies, undocumented resilience, geographies, space and place, and revolutionary art. Beatriz interned at the National Museum of American History where she researched the ways in which undocumented immigrant artists utilize social media tools to foster collaboration and create digital safe spaces. Prior to joining the Hood Museum of Art, Beatriz worked as a Community Fellow at Immigrant Justice Corps.

Comments are closed.