Matthew Schnell '22

Introdution

I am watching week five of the college football season. The Michigan Wolverines face off against the Northwestern Wildcats. Michigan takes the opening kickoff from its own endzone and elects to return it, starting from their own 17-yard line. On their next possession, after a Northwestern touchdown, the Wolverines return it to their 14. Here are the Wolverines ensuing kickoff returns: 10 yards to the 31, 18 yards to the 21. Michigan needed a fourth-quarter comeback to beat the upset-minded Wildcats 20-17. Yet as I watched the game, I noticed time and time again, Michigan chose to return the ball, turning down the option of a touchback and starting at their own 25. In total, Michigan lost 17 yards of field position by returning the kickoff. Sure, 17 yards might not sound like a lot, but in a narrow game, every yard goes a long way to helping your team win.

The NCAA recently changed its rules for this past college football season. Most notably, the NCAA allowed fair catches inside the 25 yard-line. So, for example, if a team does a short kick to the opposing team’s 11 yard-line, they can wave for a fair-catch and start their drive at the 25 yard-line. The goal of this rule is to limit kickoff returns, hoping teams would take advantage of the new bylaws and start the majority of their possessions out on the 25. After watching Michigan come short of the 25 yard-line 75 percent of the time in their close game against Northwestern, I began to wonder why teams still elect to return the ball. Does the possibility of a touchdown or great field position outweigh starting close to a team’s own endzone Does the time of the game change the team’s decision to return a kick? How often do teams actually succeed in getting past the 25 yard-line?

Statistical Methodology

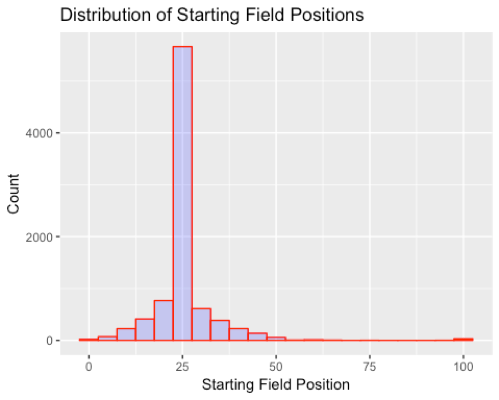

To answer these questions, I took every single kickoff and its result from ESPN’s play-by-play summaries. I stored these plays into a file, where I parsed the data into an excel file. The spreadsheet contained kickoff distance, time of game, if the kick was returned, the return distance, the starting field position after penalties (if a flag was thrown on the play), and if the team either returned the kickoff for a touchdown or turned the ball over. The data was taken before Bowl games. Below is the distribution of starting field positions from each kickoff:

The histogram above highlights the high majority of touchbacks that come from kickoffs. Teams kickoff from the 35 yard-line, so this is expected. Now let’s look at the distribution of starting field positions given both return and that the kick went farther than 40 yards (reaching the 25 yard-line):

This histogram is similar to the previous one, with a normal distribution centered around 25. One thing to note is the few outliers, where the teams returned the kickoff for a touchdown. The mean starting field position given return is 25.67, which is actually slightly greater than the starting field-position coming from just-taking a touchback. Approximately 55 percent of returns fell short of the 25 yard-line.

To test the significance of the data, I ran a one-sample t-test using a level of significance of 0.05. The null hypothesis is 𝜇 = 25 (since we want to see if the starting field-position given return is much better than just taking a touchback) while the alternative hypothesis is 𝜇 > 25. Our standard deviation will be from the distribution above, which is equal to 11.74, and the sample size is equal to 3,573. The large standard deviation is most likely due to the returns for a touchdown. With 3,572 degrees of freedom, the p-value is 0.556, meaning we do not have statistical evidence against the null hypothesis. This shows that there is not any clear advantage in returning a kick.

One other question I wanted to look at is if teams are more likely to return kicks depending on the quarter. I anticipated that teams are riskier in their decisions in the fourth quarter, where they could need a major swing in momentum as the game comes to a close. Here is a bar plot of the number of returns in each quarter:

At first glance, the graph highlights that teams return less kicks in the fourth quarter. Let’s run a chi-squared goodness-of-fit test to see if there is an equal distribution. The null hypothesis is that there is an equal number of kicks returned in each quarter, while the alternative hypothesis is that there is some sort of difference. The chi-squared statistic is equal to 92.186 with the degrees of freedom equal to 3. This gives us a p-value very close to 0, meaning we can reject the null hypothesis and that there appears to be some sort of difference between when teams elect to return. One fascinating thing, looking at the bar-chart above, is that the lowest amount of returns occur in the fourth quarter, which, again, is much different than anticipated.

Discussion

Prior to my research, I expected that returning kickoffs are more hurtful than beneficial. Teams lose yardage when they bring the ball out from a kickoff instead of taking the touchback, which can go a long way in a one-score game. My research proved the same: there is no strong statistical support that teams start better than the 25 yard-line when returning a kick; teams who did decide to return the kickoff failed in reaching the 25 yard-line 55 percent of the time. One explanation for why there appears to be better field position can be explained by touchdown returns. In the rare instance of a team scoring off of the kickoff, which occurs only 0.9 percent of the time, the team technically starts at the 100 yard-line, skewing the distribution slightly to the right. Kickoff returns for a touchdown may make teams more enticed to bring it out in the first place. The risk of turnovers is another reason teams should not return kicks. Teams fumbled the kickoff away approximately 1 percent of the time. Again, this may seem like such a small fraction of the time, but in a tight contest teams may not want to even chance the possibility of a turnover. Further research could look at whether teams more or less likely to return kicks end up actually winning more games.