“The Daniel Webster Project in Ancient and Modern Studies at Dartmouth is inspired by the lasting ideals of liberal education–that the past is not a tomb of dead ideas, to be discarded or forgotten, but a living treasury whose power to inspire and provoke can never be exhausted; that an educated person is one who has joined the fractious but unbroken conversation that links the oldest works in our tradition to the great intellectual and artistic achievements of our time; and that a respectful but critical engagement with this tradition remains an essential condition of responsible citizenship even today. These ideals have long been the animating core of collegiate education at Dartmouth and elsewhere. The Daniel Webster Project in Ancient and Modern Studies gives them continuing life in the new century we’ve just begun.”—Anthony T. Kronman, Sterling Professor of Law, Yale University.

“The Daniel Webster Project in Ancient and Modern Studies at Dartmouth is inspired by the lasting ideals of liberal education–that the past is not a tomb of dead ideas, to be discarded or forgotten, but a living treasury whose power to inspire and provoke can never be exhausted; that an educated person is one who has joined the fractious but unbroken conversation that links the oldest works in our tradition to the great intellectual and artistic achievements of our time; and that a respectful but critical engagement with this tradition remains an essential condition of responsible citizenship even today. These ideals have long been the animating core of collegiate education at Dartmouth and elsewhere. The Daniel Webster Project in Ancient and Modern Studies gives them continuing life in the new century we’ve just begun.”—Anthony T. Kronman, Sterling Professor of Law, Yale University.

What is the Daniel Webster Project in Ancient and Modern Studies? It is a new faculty initiative to enhance the liberal arts experience at Dartmouth College by bringing ancient and modern perspectives to bear on issues of permanent moral and political importance. The Daniel Webster Project in Ancient and Modern Studies was created by Professor James B. Murphy in consultation with his faculty friends across the divisions of the College. The Daniel Webster Project in Ancient and Modern Studies has never been officially reviewed, endorsed or rejected by Dartmouth College.

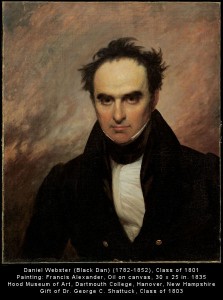

The Webster Project will sponsor regular lectures, conferences, and curriculum proposals designed to enrich the Dartmouth College experience. We aim to bring faculty, students, and alumni/ae together around the core ideals of liberal education. Daniel Webster, class of 1801, remains a compelling model of how the liberal arts can serve the highest ideals of American political life. As a renowned orator, in the tradition of Demosthenes and Cicero, Webster always explicitly engaged Greek and Roman political thought in his arguments about the American republic, federalism, and slavery. He is an exemplar of how liberal learning illuminates the most pressing moral and political issues.

The structure and focus of a liberal arts education are today threatened by the inundation of information, the explosion of new disciplines, and the fragmentation of knowledge. One especially disturbing consequence of this avalanche of new information has been the growing separation between those who study ancient arts and sciences and those who study modern arts and sciences. A century ago, every philosopher knew ancient philosophy, every scientist knew ancient science, and every student of literature knew ancient literature. It was the bringing to bear of ancient knowledge to modern pursuits that defined the liberally educated person. Today, however, we must make a special intellectual and institutional provision to bring ancient and modern learning into fruitful dialogue. The vitality of ancient learning depends upon the continuous effort to bring modern perspectives to bear upon classical ideas just as modern learning is immeasurably enriched by the ancient insights. Ironically, progress in modern arts and sciences often results directly from a return to the ancients. Indeed, the birth of modernity in the Italian Renaissance was itself a rebirth of ancient art and science. The Protestant reformers looked to ancient Christianity for inspiration, Marx found communism in Plato, Freud found his family romance in Sophocles, and Dalton found the atomic theory of matter in Democritus.

In his allegory of the cave, Plato reveals how a liberal education liberates a person from the transient and parochial opinions of his or her own particular society. For several reasons, the best way to liberate us from our own contemporary cave is to engage the very different world of ancient art and science. It is often said that the past is another country, but the ancient past is another world entirely. A superficial confrontation with the past leads us either to condescend to our ancestors guided by our presumptions of progress and superiority or to wax nostalgic for the beauties of a world now lost to us. But a deeper confrontation with the past leads us to see that our contemporary world is just as parochial as was their ancient world. We come to reflect that just as some of what the ancients thought was true turned out not to be, so some of what we assume is true will turn out not to be. The best way to surface our deepest assumptions and to evaluate them freshly is to confront the very different assumptions and views of the ancients. When, for example, Aristotle tells us that “no child could be described as happy” we are shocked into realizing that our notion of happiness must be very different from his. We can no longer assume that our view of happiness is the only or the best view. Ancient thought is similar enough to our own thought to make comparisons possible and different enough to make comparisons fruitful. To understand our own views about democracy, race, empire, war, federalism, education, markets, and equality, there is nothing more illuminating than the contrast with ancient views.

The Daniel Webster Project in Ancient and Modern Studies will tap the creativity and initiative of the Dartmouth faculty to offer lectures, conferences, symposia, and seminars designed to enrich our collegiate community through discussions of urgent moral and political questions informed by the broad perspectives of the liberal arts.