by Betty Kim

Introduction

In my last two blog posts for this three-part series, I talked about collaging with the Brut — the first post was a walk-through of the digital collaging process, and the second of the analog collaging process. In this post, I’ll talk about the differences between the two, comparing and contrasting the theoretical and technical obstacles I encountered during each experience.

Raw Material

I’ll start by pointing out some straightforward differences between analog and digital collaging: the limitations imposed by raw material. By “raw material,” I just mean materials that will go into a collage that have not yet been cut, pasted, or otherwise altered yet. (Although, perhaps the materials I used can’t even be called “raw material,” since I wasn’t using the original Brut manuscript — taking a photograph of an object alters its appearance, and this photo-taking process is its own artistic choice.) Thus, the artistic process began with a rather loaded decision: I had to decide which photos of the manuscript to use. Which particular representation or copy of the original would be best for my purposes?

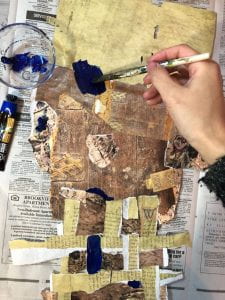

For the digital collages, I only used photos I had taken myself at Rauner; the Dartmouth Library’s scan of the Brut captured entire pages of the manuscript, but I was more interested in isolating small parts of those pages, decontextualizing and recontextualizing them in my collage. Instead of using the full-page scans, I used my own photos of the manuscript, working with parts I found most visually captivating. For the analog collage, however, I decided not to use my own photos, and instead printed out the scans from the DxDL website; for this collage, I was more interested in trying to replicate the experience of collaging with the real manuscript. That is, I wanted the copied pages of the Brut I was cutting and pasting to be to scale (at least relatively). Thus, the trajectory of the analog and digital collages were very different before I even started doing things like cutting and pasting the material I began with.

Technique: Cut, Paste, Undo, Redo

The differences only got more drastic once I actually started working with the raw material. While it can already feel like there are “too many choices” within analog collaging, digital collaging feels even more overwhelming or paralyzing. With analog collaging, for example, it’s not possible to rescale the materials you already have, or adjust the color balance without re-printing the image completely. Plus, you can’t click “undo” on a whim with analog collaging, which is very easy to do when you’re working with a digital program. For example, if I want to see how my Procreate collage looked before I made a split-second decision, I can tap with two fingers to undo. A perfect “undoing” process would be pretty much impossible with an analog collage; at worst, the use of glue or tape could destroy part of the collage.

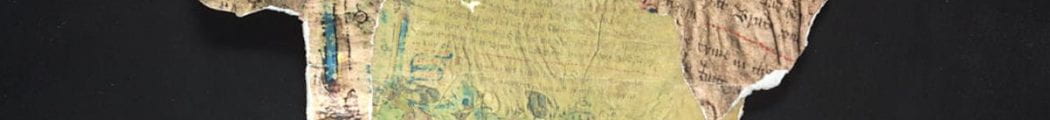

Another major obstacle with digital collaging is the flattening of angles, wrinkles, textures, and so on. In other words, it’s difficult to get a sense of how the material fits together aesthetically just by touching it and moving things around based on intuition. This experiment was meant to be an exercise in playing with the Brut’s visual elements, as if I were taking the real manuscript and allowing myself to take it apart and put it back together. This feeling can’t be replicated ideally on a digital program, in which you’re cutting by moving a stylus against the screen, pasting by pressing a button, and so on.

However, this “flattening” that I originally observed in digital photography or collage isn’t exclusive to art done on a digital interface; if you’re using print-outs of a digital photograph to create an analog collage, this flattened affect still comes into play, since most printers can’t replicate the texture of an original manuscript. Actually, there is perhaps an even more dramatic flattening effect in analog collaging because of the added step of having to print out a photo or scan before starting work with the collage. In digital collaging, the flattening effect mostly pertains to the haptics rather than visuals; since all you’re touching is a glass screen, it’s harder to get a textural sense of the materials you’re working with. However, the resulting digital collage maintains a fairly satisfying visual texture compared to the analog collages; this is because the only 3D to 2D conversion in digital collaging is the very first step, that is, taking photos of the original manuscript for collaging material.

A thought experiment

This artistic obstacle (the flattening effect produced when you take a photo of a photo of a photo) not only affects the creative process, but can also point us towards some interesting questions about the idea of “remixing” an original work.

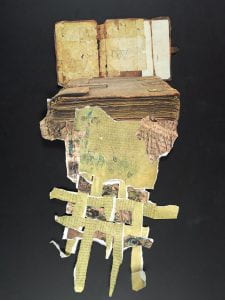

I want to approach this issue with a thought experiment: what possibilities would creating a 3D-printed facsimile of the Dartmouth Brut — exactly as it is — open to a collage/multimedia artist? With today’s technologies, it wouldn’t be impossible. Collaging with a 3D-printed facsimile would remove all the obstacles associated with this “flattening,” removing the need to print out photos of the manuscript to create collage material. It would, in fact, allow us to cut, paste, destroy, and reorganize a manuscript that looked and felt almost exactly like the original.

I imagine this would give the artist a perverse joy unparalleled by any other kind of collaging experience — even ripping up and gluing a print-out of a photograph of the manuscript felt gleefully wrong.

The facsimile would also be a valuable learning tool; instead of just studying a typed edition and occasionally getting to visit Rauner to see the original, scholars could have their own copies of the manuscript in its original form to take home with them and even keep forever. 3D-printed facsimiles would also be incredibly useful for the manuscript’s travel capabilities. Imagine having multiple copies of a unique manuscript — the Dartmouth Brut’s clones would ensure that the Brut could stay safely in Rauner, while the clones go off to different institutions to be studied side-by-side with other Brut manuscripts.

(Though her facsimile wasn’t created for the aforementioned purposes, a project in the same vein has been undertaken by Deborah Howe. While the Brut was being digitized, she explored the possibility of rebinding it by creating a facsimile cover, plus a facsimile text block made of paper, tinted to resemble parchment.)

Conclusion

Though each process yielded a lot of valuable insight in and of itself, juxtaposing the representational potential of each form hones in on big-picture questions I believe are important to begin understanding the significance of collage as remix. Here are some of the questions I kept in mind as I thought and wrote about my experiences collaging with (images of) the Brut:

- What is the opposite of “digital?” Does it vary by context? (Physical? Analog? Material? Haptic?)

- As we engage in the actions of collage — cutting, copying, and pasting (whether digitally or not) — how far from the original are we getting? At what point does the collage become unrecognizable as the Brut? Does it matter?

- What is the point of making collages with this material? What can we learn from this process? What can this type of artistic “study” tell us about the manuscript that simply looking at and reading about the original manuscript cannot?

I definitely don’t have the answers to these questions myself, but I think they are useful as guiding concepts as we observe the ”remix” process.

Thank you for coming with me on this little journey! Collage has always been my favorite form of “remix”— for many years, I’ve collected photographs, magazines, books, and other materials (vintage, modern, physical, and digital) and used collage to try and find unexpected truths about the world around me. To me, collage is about taking images out of context and placing them into a new context, putting unexpected images and ideas in conversation with each other, so it seemed like a perfect way to explore the visual language of the Brut manuscript. Though I’m coming away with more questions than answers, I’m thankful for the opportunity I had to observe and “edit” the manuscript through my own artistic lens, and hope you enjoyed reading my posts!