Last week, I had the honor to participate in the celebration of the 25th anniversary of Rauner Special Collection Library. Throughout the week, people from many areas of campus and the community had the chance to engage with a variety of special collection materials. For me, the panel on research provided a great opportunity to reflect on Remix at (almost) 10 years! The occasion became an unexpected new opportunity to pursue the Remix mission to analyze how digital tools shape knowledge: right before speaking, it occurred to me to record myself and to use an automated transcription tool to quickly turn my remarks into a more durable blog post. This process was illuminating!

- First, editing the transcript took much longer than I expected (hence the delay in this post).

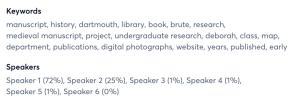

- Second, the tool, Otter.ai, did more than just transcribe the audio: it extracted a summary as well as a “task list.” I didn’t expect to receive an assignment from an app! The tasks though are rather accurate and strangely motivating.

- Third, precision can just as easily lead to error. Due to variations in my voice (I think), the tool identified 5 speakers on the audio—and named one of the collaborators mentioned in the text as a co-speaker (a great example of how digital tools themselves become co-authors).

If I had more time…I would truly “remix” this experience by running my audio file through other voice-to-text transcription tools, compare the outputs, and assess what those comparisons teach us about the state of large language models (LLMs) and the automation of natural language processing (aka reading and writing). But those experiments will have to wait for another day.

Edited Transcript

Keywords [protected from text copying]

, , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , ,

Speakers [protected from text copying]

, , , , ,

[Image of Keywords and Speakers]

Good afternoon. Good morning, everyone. Can you hear me? Fortunately, I travel with my own amp, because I think the mics are not broadcasting for you. Hopefully you can hear me I have a very low voice for various reasons.

I’m Michelle Warren, just to remind you if you forgot from a little while ago, and I arrived at Dartmouth in 2006, the same year as this medieval manuscript that’s sitting on the table over there, third book down, and that is the subject of my research and my discussion today– known now as the Dartmouth Brut.

The very first email I got after I signed my contract to come to Dartmouth was: “Guess what, we bought a medieval manuscript!” I was like, Cool. I don’t really do research related to that topic, or on manuscripts. That sounds nice though. A lot of people clearly expected me to arrive at Dartmouth and take up research on the Brut. I really had no intention of doing that. I did, however, teach a class in 2008 on Chaucer in the English department, and we did our ritual trip to Rauner to look at manuscripts. And I had a student in that class who saw this book, and just went ballistic. Emily Ulrich, class of 2011, ended up writing her honors thesis inspired more or less by folios 10v and 11r, which are open for you to look at on the table here. These pages, as well as many others, are full of annotations.

And so I’m here to tell you that the “research versus teaching” thing is not a real division. I would never have become a researcher of manuscripts or of Digital Humanities, if it weren’t for teaching my class and getting progressively inspired through Emily and a succession of other undergraduate students and library fellows. They are all listed my alumni team page. There are a lot of them, and they go back pretty far. Colleagues in the Dartmouth library have also consistently supported this work with enthusiasm.

You might not think there’s any connection between what I might have to say about a medieval book, and the really important work on histories of enslavement that Deborah King just talked about. But there is a connection, which is ledgers and account books, and also merchants–how they relate to the knowledge of history, the erasures of history, the commemoration of past events. This is a picture of a book cover made by Deborah Howe from the Conservation Department, and this is a picture of the 16th century cover for this book. The Brut manuscript is essentially a history of England from its legendary origins, after the Trojan War and then after the Crucifixion, through to the legendary events of King Arthur and Merlin, on to the late for the early 1400s. The Brut is a national history and was the most popular history of England for many centuries, all the way to the late 1700s. The binding of the book is the same kind of binding that is used for ledgers and account books. It suggests that this was a merchant’s book at one time, and that was related to a mercantile interest to identify with the nation and the empire through knowledge of its history. This picture is a beautiful reproduction, or really a theory of the original cover that Deborah made herself, which is really shows you the kind of stitching that is needed to for an account book. And here’s another one from the Folger Shakespeare Library. The book is made so that it can get bigger and bigger as more pages are added. This is crucial evidence from physical materials, which are now only available to you via these digital photographs. They are not over there on the table, and one of them doesn’t even exist anymore. It got lost because it wasn’t considered important enough to be given an accession number.

I have been also thinking about this project in relation to the ways that a book like this could be purchased in 2006. It’s only been in public access at Rauner for less than 20 years. The year 2026, will be its 20th anniversary in the public sphere. In our About section, we have some research that I did on the endowment fund that enabled this purchase to happen. We have a land acknowledgement for the project that includes broad discussion around the college’s Indigenous history as well as histories of enslavement. And the specific history of the William L. Bryant Foundation, created by William J. Bryant, Dartmouth Class of 1925.

One of the principles of my research project is: one book, many tools. How many ways can we study a single book? It has turned out that our main subject of research is the library, itself. So we look at the funding structures. I have also collaborated with librarians in almost every department from digital imaging to conservation. And this is itself largely what we study.

I’ve been doing this for almost 10 years, starting in 2015.

It really was the digitization of the manuscript, very early on in 2009, that made all the research possible. As people were expecting me to do things with the Brut, I couldn’t quite figure out how, because for other scholars to have anything to say, they would have to have you come here and spend a lot of hours reading it and leafing through it, and it was a time investment with no obvious payoff, unless you kind of already knew something about what was inside. So once the manuscript was digitized, I could imagine doing a conference, because people could look at the digitized copy and they could decide if I invite them that they may or may not be willing to come, and whether they would have something to say. The conference took place in 2011, followed by a collection of essays in 2014, which is now part of our publishing history.

The website is designed to make it easy for you to find the official publications and the remix experiments. The website itself, however, has become our main research output. I’ve been navigating it silently here to show you different things. But we have on this homepage, essentially, a series of pathways into the work, whether it’s the official publications, the projects we’ve made, some of which are not technically officially published, but are born-digital and live only on the website. And then also some discussion of how we make things with tools, both digital tools and material tools. And you can also check out our wish list of things we might want to do, or make a suggestion (we haven’t actually ever received a suggestion. I keep it up there, ever hopeful that someone might want to do that).

The website is, in a sense, teaching people how we do research. There’s a lot of stuff on there that is from the undergraduate research assistants who were like, “What is Omeka?” Here’s what Bay learned about Omeka. And here’s how we used it on our project. Not so useful once you’ve done it. But everyone has to learn that for the first time at some point. We also compared Omeka with Scalar, using the same text and images. And so there’s a lot of material on the website that is really made just for teaching people how research develops, whether they’re experienced or just beginning.

Just last week, my current research assistant Brian Guo, class of 2025, asked me this really sharp question as undergraduate RAs will tend to do. He’s been funded as a Presidential Scholar through the Undergraduate Research Office (putting in a plug for UGAR, which has paid for many of my research assistants over these years). Brian asked: what has been accomplished with this project? And how do I feel about it? I thought about this question as a way to conclude with you today. Very thought provoking, as I ask myself periodically, why am I still doing this? It’s been quite a while now…

What have we accomplished? Our projects page shows that our very first accomplishments were the series of digital tool assessments written by Bay ByrneSim (and look, a post by Laura Braunstein!). And then, because we had those blog posts, we were able to publish an article in an actual peer reviewed academic journal that made all those reflections we’d been doing more official and structured and organized. We then started a very long process of putting the Dartmouth Brut on the map. It was another RA, an Edward Connery Lathem ’51 Library Fellow, who put the Brut on a literal map. As I mentioned, it had been in private hands until 2006. All of the previous scholarship on the Brut, of which there several catalogs and lists and assessments of the text, there are many variations and about two hundred surviving manuscripts. But no mention of this particular text because no modern scholar had been able to read it because it was in a private setting for almost its entire life until it came to Dartmouth.

One of our biggest accomplishments is the Handlist of Brut Manuscripts. This is a data set of library records from around the world, now owned by the Dartmouth library and maintained by the library. This was a collaborative project with another library and with another scholar of the Brut who became the curator of rare books at University of Florida. We wrote an article about our process and we have this browsable directory that is part of the library’s digital collections—connecting the Dartmouth Brut at last to the other manuscripts in the corpus. And would you believe it, since we published the handlist, a new Brut manuscript has been identified! One of our entries that says “location unknown” is now known—located at Leeds University Library, a new acquisition for the Brotherton Special Collections. Out of the blue, I received an email from a colleague at Leeds explaining that they had used our handlist while cataloguing and realized that their acquisition was in fact the same book that we had listed as associated with a person named Denys Spittle. We will be having to update and rearrange our knowledge of the Brut descriptions. Prior to June 2023, this manuscript was not publicly traceable. Stay tuned for more information. The colleagues at Leeds used our handlist to locate their new manuscript—and we will now revise our handlist to locate their new manuscript. Like the Dartmouth Brut, the (now) Leeds Brut is not described in any prior assessments or scholarship on the Brut corpus. Soon, it will be more discoverable and more connected to the corpus, opening up new opportunities for research.

So what have we accomplished? Some publications, some art, some maps, some collaborations. Mainly, though, curiosity. The persistent pursuit of curiosity has driven Remix project. And I think I’ll keep chronicling these experiments as long as there are any students curious to do it with me. Thank you.

Summary (unedited output)

Michelle Warren and Deborah Howe discussed the connection between history and commerce in medieval manuscripts, highlighting the significance of understanding the mercantile interests of the time. Speaker 2 shared their research project on a book purchased in 2006, emphasizing the value of digitization and collaboration in making research possible. Speaker 3 added their thoughts on the project’s progress, and Speaker 2 discussed the importance of curiosity in scholarship, highlighting their collaborative project with another library and a scholar at the University of Florida. They expressed excitement about the potential for continued collaboration and curiosity-driven research.

Action Items (unedited output)

- Continue developing the Brut manuscript research website to teach people how research develops and share outputs from the project. Michelle Warren and her research assistants will work on this.

- Update the handlist of surviving Brut manuscripts around the world as new manuscripts are discovered. Michelle Warren and the Dartmouth library will collaborate on maintaining this resource.

- Publish an update on the newly discovered Brut manuscript at Leeds University Library, which will require rearranging the unknown manuscript information on the research website. Michelle Warren and her collaborator will work on this.

Outline (unedited output)

Medieval manuscripts, digitization, and research methods.

- Michelle Warren discusses research on medieval manuscripts, teaching, and student inspiration.

- Deborah Howell’s analysis of the Brink manuscript reveals its connection to mercantile history and account books.

- Researcher studies book’s history, funding structures, and digitization impact.

Research project accomplishments, publications, and collaboration.

- Speaker 2 discusses their research project’s website as a teaching tool for undergraduate research assistants.

- Speaker 2 reflects on their work, mentioning accomplishments such as creating digital tools and publishing an article in an academic journal.

- Scholar collaborates with library, discovers new route, updates knowledge.