When Darwin published On the Origin of Species 150 years ago, he may not have realized the rippling effects it would have throughout history. The work engendered a spark in scientists, educators, and lawyers. Both in the United States and abroad, policy surrounding the inclusion of evolution in education has changed as well. From the infamous Scopes trial to the more recent Kitzmiller et al. vs. Dover, rulings on evolution in education reflect the times. Although these court cases have received the most attention, they are by no means a reflection of educational policies toward evolution on the whole. The early 20th century provides an excellent instance of how evolution in education has varied across the nation. Dartmouth’s approach toward evolution in education serves as a clear example of deviation from concepts expressed in more popularized legal conflict.

The first anti-evolution law in the United States came into effect in 1923 when Oklahoma prohibited Darwinism from public school science texts (1). Between 1921 and 1929, thirty-seven anti-evolution bills were introduced in twenty states (1). In 1925, when Tennessee passed the Butler Act prohibiting “any theory that denies the story of the Divine Creation of man as taught in the Bible, and [teaches] instead that man has descended from a lower order of animals,” the American Civil Liberties Union of New York City decided to act (2). Their work eventually led to the famous “Scopes Monkey Trial,” in which teacher John Scopes was convicted and fined $100 for teaching evolution (3).

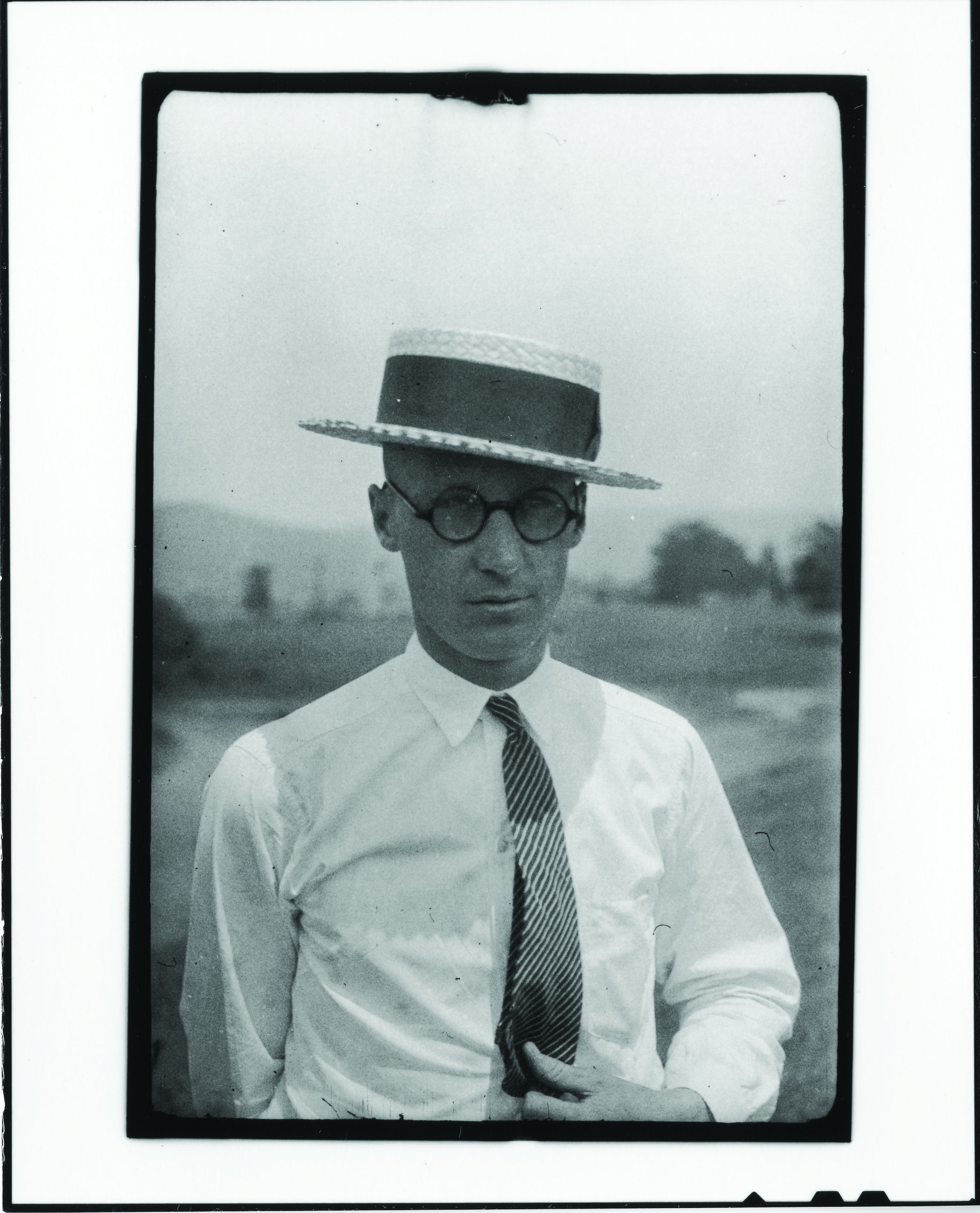

John Scopes, a Tennessee high school teacher who was tried and convicted for teaching evolution in 1925.

Meanwhile at Dartmouth, professor William Patten had already made evolution a staple within the college’s curriculum. Patten’s inclusion of evolution may have begun as early as 1898 within the course Comparative Anatomy of Vertebrates. The object of the course was to “illustrate the evolution of the vertebrate type of animals from the lowest fishes and related forms, up to man, and to discuss some of the conditions that are coincident with, or determine the progressive modification of various vertebrate organs” (4). By 1921 Patten headed the course Evolution, a requirement for all freshmen that included “theories of evolution; conservation and endowment in nature; inheritance, germinal, social; the growth of man as an individual and as a race” (5).

The Course

Patten viewed the course on evolution as a way to link the sciences and other disciplines with a common thread. He explains within “Why I Teach Evolution,” an article published in Scientific Monthly in 1942, that evolution is “a concept that not only helps us to understand what is going on within us and about us, but one that is constantly leading to new revelations in every field of human thought and practice. It is the one basic idea implied, or specifically expressed, in every phase of college and university teaching” (6). He aimed to use the course to simplify and clarify the most perplexing problems in science and beyond for his freshmen audiences. In the course guide he cites the importance of Darwin’s theory in accomplishing this task because it joined “the different tributaries of Man’s mental life… [in] one current of thought, moved by a common mental compulsion” (7). Beginning the course with lectures on growth, Patten passed the torch to professors within other departments to illustrate continuity with subjects like ethics, physics, and ecology. Although the outside world may have misidentified his efforts as a crusade against religion, Patten never mentions a desire to fuel tension. In fact, he writes, “The study of evolution as a whole more than anything else will help to minimize the antagonism between religiously minded people and scientifically minded people and will help them to work more peacefully and happy together” (6). Finally, Patten fully embraced and defended evolution’s fundamental nature as he warned freshmen, “Doubtless many of your cherished notions will be rudely shattered, and new ones grow up to take their place. But that is what you and I are here for. That is what education means. But you need not fear to know the Truth. You will find that to discover what is nearer Truth, and to use it for your own betterment, and thereby for others, is the greatest pleasure there is in life” (7).

The Public Responds

Initiating such a course took courage from Patten and support from his peers; however, support in most cases came later rather than earlier. In a later speech to Alumni Council, Patten recalled: “Making Evolution a required course for all freshmen was a radical innovation in college education and met with great opposition from all quarters, from alumni, parents, faculty and students. Whoever heard of such a thing? It was contrary to all pedagogical principles. It was not science but just hot air. It would encourage the destruction of whatever religion was left in college life, and so on… At the very outset a surprising number of freshmen shut tight their jaws and refused any mental pabulum we had to offer, just because it savored that ungodly thing, evolution. Upperclassmen and occasional various instructors laughed at them as the goats of an ill advised educational experiment.” (8)

The initial discomfort voiced by the nation in response to the new Dartmouth course subsided over time. Patten explains: “But after two or three years most of this antagonism disappeared, and we were more and more impressed with the maturity and receptivity of the average freshman. Many of them have thought deeply on the larger aspects of our problems and often express their opinions with a comprehension of the points at issue and in a literary form that any instructor well might envy.” (8)

By 1923, the Dartmouth community seemed to accept the course. The response to a long-awaited visit from William Jennings Bryan, who would go on to lead the prosecution for the Scopes trial, exemplifies the students’ attitude. The topic of Bryan’s talk, “Science vs. Evolution,” allowed him to express indirect disdain for Patten’s efforts. Although “the problems which he had raised were the chief topics of conversation whenever Dartmouth men came together,” their views on the matter were relatively unaffected (9). Furthermore, evidence shows that the students drew distinctions between Bryan’s oratorical ability and the logic that he employed (9). Like his students, Patten did not let the visit go unnoticed. His response to Bryan’s visit appeared in a 1924 issue of the New York Times where he asks, “Would it not be better to use your great talents in helping to bring about a better understanding between two extremes of human life instead of antagonizing them?” (10). It appeared that evolution in education, at least at Dartmouth, was here to stay.

Even if voices of support seemed few and far between at first, Patten was not alone in his endeavor. Local support let Patten successfully take what many would perceive to be a professional risk. Within a series of letters, Dartmouth’s current president Ernest Hopkins expressed continual encouragement of Patten’s actions. In 1922, the American Association of University Professors published a segment about Dartmouth courses, particularly Evolution, in the pamphlet “Special Courses for Freshmen.” Noting this, Hopkins urges Patten “to do everything possible to make this course of maximum advantage, and the more so because it is attracting so much attention outside” (8). Two years later, Hopkins again writes to Patten about a recent meeting pertaining to the college curriculum. He lauds:

“I wish you might have been behind the scenes and heard their expressed admiration for you and the value which they placed upon the course in Evolution as of maximum worth to them in their college course. Nothing could be more gratifying in life than to have made such an impression on such a group of men, and I want you to have the happiness of knowing in regard to this.” (8)

Thankful for the support, Patten later explains in a speech to the Alumni council, “President Hopkins, who had to bear the brunt of the criticism, gallantly withstood the storm and gave us every assurance of his confidence and willingness to assist us in every way” (8). While support seemed to have originated in the College, by 1931 widespread praise had reached Patten. A noted American zoologist, William Gregory, named Patten as one of the “very few Americans who are maintaining the honor of the country” in the origin and early history of vertebrates (8). Moreover, a Norwegian paleontologist, Anatol Heintz, writes, “In Norway, people are very interested in evolution” and goes on to request translation of some of Patten’s work (8). Once again, in contrast to the proceedings happening in the American south, support for the required teaching of evolution grew.

A Country Divided

By the time the evolution course had kicked into high gear at Dartmouth, the courts were just beginning to get a glimpse of what was to come. Credited for introducing the American public to the issue of evolution in education, the Scopes trial arguably still affects judicial actions. Its context provided the perfect set up for the popularized clash between William Jennings Bryan and Clarence Darrow. The end of World War I left Americans rejecting social Darwinism as a result of its similarities to Germanic militarism (11). The additional increase in enrollment in secondary education meant more homes were vulnerable to evolution’s expansion, and the mounting tension between liberal Christians and evangelicals needed an outlet. Although these factors heavily contributed to the trial’s initiation and subsequent popularity, a few lesser-known motives came into play as well. John Scopes, who substituted for the regular biology teacher on the date in question, allowed himself to be prosecuted to test the constitutionality of the law on behalf of the ACLU (11). Furthermore, the town of Dayton, Tennessee, the location of the trial, saw the trial as an opportunity for nationwide publicity and economic growth. The result left both parties satisfied. After a day of deliberation, a judge ruled that the State had the right to control public education. Then the ACLU pushed to take the case to the Tennessee Supreme Court, which strategically reversed Scopes’ conviction thereby depriving him of the ability to appeal. The fundamentalists achieved what they wanted. Civic Biology, the book in question, was edited so that it no longer mentioned evolution and the Butler Act remained in place until the 1960s; however, the ACLU brought the issue to the forefront and turned Bryan into a fool (11).

The evident differences between the Tennessee rulings and the Dartmouth curriculum eventually made their way to the press. In June of 1923, an article by Clifford Orr that appeared in the Boston Evening Transcript covered the stark contrast. Interviews with Dartmouth students, President Hopkins, and Professor Patten made their way into the article. It even detailed the story of a student who came to Dartmouth after being raised under stern Southern fundamentalists. Orr writes:

“Bryan visited Dartmouth in 1923 and saw the horrible danger of enlightenment to which the boy was exposed. He reported affairs to the boy’s parents and they started to withdraw him from college. He did not want to leave, however, and was finally allowed to finish his year. At the end of the evolution course, he went to Professor Patten and thanked him saying, ‘At last I can meet Mr. Bryan and hold my ground against him!’” (8)

It seems the course finally garnered the popularity that Hopkins so desired in his earlier writings. Orr’s article featured an interesting remark in which Hopkins states, “I hope it is not possible for a man to be graduated from any first-class college a fundamentalist.” Orr continues, “And then he said that he might even go further and define a first-class college as one from which a fundamentalist could not possibly be graduated!” (8). The sensationalist style of the article suggests an effort to entertain, but at its root lay a problem for which the nation did not have a solution.

Death and Continuity

Patten’s work and the Scopes trial have left lasting repercussions. Popularized court cases like Epperson vs. Arkansas (1968), McLean vs. Arkansas Board of Education (1982) , Edwards vs. Aguillard (1987), and Kitzmiller et al. vs. Dover (2005) show that the issues of the early 20th century have not yet been laid to rest. Unfortunately, neither Bryan nor Patten witnessed the effects of their actions. Bryan died five days after the Scopes trial ended; Patten followed in 1932, less than a year after his resignation from the College.

Patten’s resignation came as a shock. Many commended his impact on the College. Charles Lingley, the dean of admissions at the time, composed a letter to Patten in which he states:

“I want to tell you that when I sat down at the breakfast table this morning and saw that you were retiring, my breakfast did not taste as good as it usually does. Your profound scholarship, even temperament, and abounding interest in everything that concerns people and things are qualities that are not too common. When those qualities appear altogether in one person, it is a real tragedy when the passage of time compels the college to let go of such a person. If it were not contrary to your nature and philosophy, I would earnestly urge you to tell the Trustees that you had made a great mistake in giving your age and revise the latter so as to defer your retirement for a good long infinite period.” (8)

After Patten’s death, letters made their way to his widow once again commending his profound influence. The evolution course continued under James Poole, but appears to have been disbanded after 1935.

In any case, the rich history of Patten, Bryan, and the evolution course displays the power of Darwin’s theory. Generalizations about the approach to evolution in education cannot speak for a nation. Instead, proper evaluation must include contrasting viewpoints. The presence of diversity can help a college and a country evolve; according to Darwin, it is the only thing that ever has.

References

1. B. Flynn, Thesis, Dartmouth College (1990).

2. N. Adams, Timeline: Remembering the Scopes Monkey Trial (2005). Available at http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=4723956 (26 Feb 2009).

3. PBS, Scopes Trial (2001). Available at http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/evolution/library/08/2/l_082_01.html (26 Feb 2009).

4. Dartmouth College, Officers, Regulations, and Courses (Hanover, NH 1898).

5. Dartmouth College, Officers, Regulations, and Courses (Hanover, NH 1921).

6. W. Patten, Scientific Monthly 19, 635-647 (1924). Available at http://www.jstor.org/stable/7238?origin=ads&cookieSet=1 (26 Feb 2009).

7. W. Patten, The Larger Aspects of Growth (Boston: Gorham Press, 1920).

8. W. Patten, Papers, 1879-1956 (Donated 1953).

9. M. Willey, S. Rice, Journal of Social Forces 2, 338-344 (1924). Available at http://www.brocku.ca/MeadProject/Rice/Willey_Rice_1924.html

10. W. Patten, Mr. Bryan at Dartmouth; A Reply From the Faculty to His Sweeping Denial of the Truth of the Theory of Evolution (New York Times, 1923).

11. M. Ruse, The Evolution Wars: A Guide to the Debates (ABC-CLIO, Inc., Santa Barbara, CA, 2000).

Matthew Provillus

Hi,

I read your article about evolution and I found it pretty interesting. As a believer in the Christian faith, and creation I do not buy into evolution, however unlike many naive Christians (of which there is many, my apologies) I actual do believe in part of evolution, because I bothered to research.

What I believe in is Inter-species evolution but not Intra-species evolution. So although I do not believe man develop from a fish, I do believe there are evolutionary developments inside a species.

The problem that most people have with the Christina belief, is largely based on time, however the problem here is that modern beliefs are based on Carbon dating, and much research has come out and is continuing to come that is showing major flaws in isotopic carbon dating. This research is suggesting a 10,000 year old (or about) earth, and not millions!

Thanks for a well written article