Roald Hoffman, the fall 2009 Montgomery Fellow at Dartmouth College, was born on July 18, 1937 in Zloczow, Poland. His childhood took place during a Russian occupation, and most of his relatives, including his father, were killed by Nazis during the war. By 1949, he immigrated to America and learned his sixth language, English, at a public school in the Bronx. He studied chemistry at Columbia and Harvard and began teaching undergraduate students at Cornell University. Among his numerous awards and honors in science is the 1981 Nobel Prize for Chemistry, co-won with Kenichi Fukui for developing the theory of conservation of orbital symmetry. A most literary chemist, Hoffman has also published several poems, plays and essays (1). Here, the DUJS talks to Hoffman about how his personal history has shaped his artistic and scientific endeavors.

Roald Hoffmann devised the Woodward-Hoffmann rules, which predict the three-dimensional configuration of cyclic reactions in organic chemistry.

What is the focus of your latest research?

Lately I’ve been working on a borderline of chemistry and physics in collaboration with a physics professor at Cornell, Neil Ashcroft. We’re looking at the behavior of matter under extreme conditions of pressure, like those at the center of the Earth. At those pressures the volume of a solid goes down to about one third of what it is normally, so imagine a cube of steel compressed to a third. You wouldn’t think a chemical intuition about bonding would help in this regime because it’s a rather abnormal set of conditions for normal chemistry. Gases become liquids become solids, but even more drastic things happen, so carbon dioxide which is normally a triatomic molecule O-C-O goes into a structure like that of silica or quartz. We are theoreticians so we try to predict some of these structures that the experimentalists, who are squeezing these things, will obtain under high pressure. We have recently predicted for instance that if you add a little bit of lithium to hydrogen gas, you will be able to metallize the hydrogen. It has been a dream to be able to make hydrogen into a metal. It’s presumably the way it exists in the interior of large planets.

What has been the most important development in chemistry in the last twenty years?

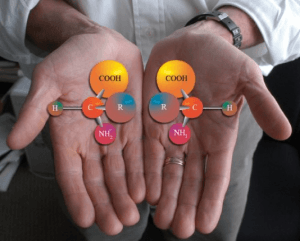

It’s difficult to say. I think perhaps it’s the ability to get extremely fine control in synthetic organic chemistry on creating molecules in one mirror image and not the other. Making a left-hand rather than a right-hand [molecule] on command. That turns out to be very important for designing drugs. Molecules that are mirror images of each other can have rather different properties. It’s not one advance but many groups have made technical progress. Many techniques have evolved from a number of people on doing this extremely efficiently. I think that is a major change in chemistry.

Why do you write poetry?

Poetry allows me to express myself in ways that are different from what I can do in science. So it is personal expression, but I also feel I have something to communicate to other people. I do write about science occasionally and I try to work in scientific metaphors. In the discussion with a poetry group they were very interested by it, a scientist writing poetry. So I have to get it out of the way by writing a few poems about science before I can write about nature or relationships or things like that. I’ve also written about my childhood in WWII.

Where does the inspiration for your poems come from?

Some of the poems are drawn from direct experience. Some of them I’m thinking about what happened, for instance there’s a poem in there “The Bond” which doesn’t refer to a chemical bond, but I was thinking about the strong tie in those terrible times between the people in a concentration camp and their guards because everything depended on the guards. That short poem is a powerful one but it comes out of thinking about what happened, not my personal experience.

It usually starts off from a phrase – two or three words that somehow mean more than the words by themselves do and rather than work off an idea I work off a group of words and build a poem. For example the phrase “a knife made of an old ram’s horn.” Usually I go through on the poems many more drafts than I do on a scientific article. This is a shorter unit of work, though some of the poems are long, like two pages, but maybe that’s because I’ve done the articles for 45 years and poems for 25 years. Poems are more like gifts and most of it comes in the beginning but most of the time I’m struggling through twenty thirty drafts – alternating between writing by hand and typing it up. The word processing helps a lot. I work harder on the poems than I do on the science.

How do you know when you are finished?

I don’t have any trouble knowing when I’m finished and usually when I’m finished with a poem I don’t revise it. There are a few exceptions. Say there are about twenty drafts about four drafts from the end, there is a feeling of closure. To some extent there is a similarity to the feeling in scientific papers. We’ve done the best job that we can. The poem or the scientific paper is not the best in the world but we’ve done what we can, so we stop.

Would you say the writing process has some parallels with research?

Yes, but there are other aspects. Often going away someplace to a different natural setting helps a lot. The nature helps to set me off to write because I need to separate myself somehow and get in a more contemplative mood. I’ve realized the power of a group of words, where their inherent tension is used. There is a certain conciseness and economy of statement, which ideally I would like to have in the science too, but science tends towards the prosaic by listing all the caveats, all the exceptions, all the possibilities or at least one tries to think of them. I think writing the poems has helped me somewhat with the science. Maybe what’s helped the papers more than the poetry is teaching, because you are forced to explain things without the mathematics to help you along. The explanation has to come in words and pictures. Somehow I got a grade in a graduate course in thermodynamics at Harvard, but really I didn’t understand thermodynamics until I taught it to first-year students. Some people in the class understand, some have trouble understanding, some are sleepy and you have to talk to them all. Also when you write a scientific paper you don’t know what the people reading it understand and somehow in the words of the paper you need to do what you do in a classroom lecture.

When teaching how do you inspire even the sluggish people?

With the mixed audience, it’s a tough balancing act. I gave a talk to the religion department about indigo as cultural history and its role in Jewish religious belief or practice – there was a little bit of science about the way indigo is transformed into a dye that is not washed out – so that your blue jeans don’t turn white after one wash, so I had to strike a balance there – how much was I going to use those words. I learned this from teaching. I think I’ve become a better researcher from my teaching experience. Usually the argument is made the other way – that you become a better teacher from doing research.

Metaphors are often used by scientists in their research, so they say “the energy to run this reaction is like climbing a hill and climbing over it.” There’s a landscape metaphor there. If you want to explain things to people it’s natural to map what is difficult to explain on something else in another field that they understand. I think scientists suppress the metaphor – they use it but they don’t put it in their papers often enough because they don’t think it’s mathematical enough to impress their colleagues. And that’s too bad. But when a scientist writes about science they are forced to use metaphor to communicate with people. And maybe the metaphor is more revealed to them and maybe they can see more of its limitations or where it can be used further. It’s a real art to write good science.

The concept of molecular chirality is best visualized by looking at one's left and right hands, which are non-superimposable mirror images of one another.

How long did you teach at Cornell?

It was my only job by choice – forty three years of teaching. I began and I did my service to Cornell. Half the time, I taught introductory chemistry, but I didn’t get tired of it. I still don’t know why because there were exasperating moments in the teaching. But there were always rewards and sort of opening people’s minds to the potentialities that were already there. The facts were not so important, someone could sit down and memorize the facts by themselves, but the relationships between the facts and the ways of thinking. But what am I – giving you something that’s not in your mind already? No, I am just facilitating you making your own connections for even the simplest thing in chemistry, like a stoichiometry problem.

Did you view teaching that way when starting?

No, not the first year but I quickly caught on about the second year. The first year I wondered why are they assigning me to teach introductory chemistry? I was scared. And some things took me a longer time to develop; for instance, I think it’s important to do demonstrations. They’re magic, they’re an exclamation point, they’re a break – sometimes the only thing students remember is the explosion. It happens, but in the hands of the teacher they combine visual and auditory senses and if the person explains what the connection is they’re very good at awakening real learning. As a theoretician it took me about ten years before I tried to do a demonstration. Now I do lots of them.

What have you learned from your students?

I didn’t realize that there were different learning styles that the kids had. Some people take things in print, some people take it in more visually or by hearing. I think you can adjust to different learning styles, but there were differences and I adjusted to that. In the forty odd years I was teaching there was a change also to a growing professionalism. More direction towards medicine and engineering than in the 60’s and 70’s. It made no difference in the ones who became chemists which was always a small fraction of the ones we were teaching. But the professionalism at an early age, meaning they and their parents wanted them to go to medical school, had an overall negative effect on the learning process. It was very hard to combat and that is why it was actually more fun to teach the non-professional course, not quite chemistry for poets but some people in the agricultural or arts colleges. They might have been starting off negatively in that they were fulfilling a requirement, but they had a chance to have an interest.

What kind of writing is most rewarding to you?

I’m actually doing more plays than I’ve done poetry in the last few years though I think I still find the poetry right now the most rewarding. I haven’t given up the science; there are co-workers who are fantastic and have kept me going, but I’ve thought a few times about stopping the science. But it’s fun to be able to use my intuition, whatever it is, some set of neural networks that’s burned in where you’re not cognizant of how you’re thinking, but you have a feeling about what will happen. For me, intuition is something that builds with time. I’ve seen lots of molecules in my life and had 500 papers on both organic and inorganic molecules – that gives me a lot of background to roam in when some new idea comes up. So the science remains lots of fun I can’t seem to give it up. Although still even in this day and having done well in my field there are frustrations. I’ve had troubles with getting funding for the kind of free-ranging explorations of what electrons are doing in any molecule under the sun. If you study fuel cells or hydrogen storage, if you have a utility or a mission, it’s easier than if you just want to understand things. I put tools in other people’s hands. I don’t hold a single patent. I’m not particularly proud of it. But the ideas that we have given the community have been used in a large number of patentable things, especially in synthesis of drugs, and I think I’m lucky in that way.

How did you feel when you first published a paper versus when you first published a poem?

Oh, both were great. The first paper was a really unimportant thing on thermal chemistry of some compounds in cement, not very exciting. It came from a summer job between high school and college from the National Bureau of Standards, now the National Institute of Standards in Technology. It was just great to see my name in print and also the next big thrill comes when somebody cites your papers. It’s especially nice when someone cites your paper who you don’t know at all, not a friend and not you yourself. I’ve written a number of papers that have been highly cited and it still gives me a good feeling to see my work is useful. On the poems there is no citation, though people may mention you. I’m just not as good a poet as I am a chemist, but that’s OK, it still gives a lot of pleasure. I have to struggle much more for publication of poetry. I’m still not at the stage that I can get a poem accepted automatically at some journal. I started sending out about 25 or 30 poems in January and I’ve gotten three of those accepted. It’s much better than I’ve done before. Some of them I send to a journal and get rejected so I send them to another one. There’s a cycle of three months maybe. Some people never answer, or when they say no, they don’t comment. It’s very different from science where reviews of a paper come in where you get referees.

Have you ever tried painting or drawing?

I haven’t. I don’t seem to be any good at it but words seem to be. I can’t do everything. I don’t play a musical instrument although I came from a musical family and if it weren’t for the war I probably would have been taking lessons and enjoyed it after a while. The war disrupted that. I’ve tried a little ceramics and I look at ceramics a lot and I write about it.

It’s been great to be here to talk. This is living out my life in the sense that I want to do both the art and science and here I’m given an opportunity to do so.

References

1. Hoffmann, Roald. “Autobiography.” The Nobel Foundation. 1992. 12 December 2009.

Leave a Reply