Maddie Brown, Biological Sciences, Spring 2020

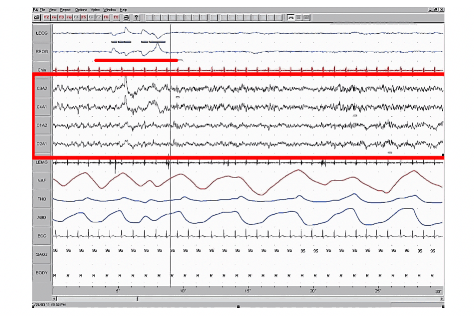

Figure 1: The red box encloses an EEG reading of the brain during REM sleep. EEG measures the electrical activity of the brain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Sleep_EEG_Stage_1.jpg

When car drives by in the middle of the night as you’re peacefully sleeping, why doesn’t the sound of a car engine work its way into your dreams? Our ears do not stop functioning while we’re asleep; otherwise, alarm clocks would be useless. How can the brain block out the sound of the fan or icemaker in order to make up a whimsical dream or frightening nightmare complete with sight, smell, and emotion?

First, it is important to know that not all sleep is created equal. ‘Light sleep’ is the first stage of the sleep cycle. As the name implies, it is relatively easy to wake a person from light sleep. Dreaming mostly happens during REM (Rapid Eye Movement) sleep – a time during the sleep cycle when the brain shows activity similar to an awake person, but the body is mostly paralyzed except for the eyes.2

Researchers from the French National Centre for Scientific Research (CNRS) and Ecole Normale Superieure (ENS-PSL) recruited eighteen volunteers to partake in morning naps so they could study how the sleeping brain interacts with external noise, particularly during dreams. Morning naps were chosen due to a high abundance of dreams. Volunteers listened to a pre-recorded tape that had a mixture of stories in French and complete gibberish, and their brain activity was monitored as they slept.1,3

The results of the study suggest that the brain treats external sound very differently in each sleep stage. During the light sleep phase, the brain filtered out information it deemed useless (the gibberish) but accepted the information it deemed relevant (the French stories). However, this was not the case for REM sleep. When the volunteers experienced rapid eye movement (indicating they were dreaming) the brain actively blocked out all external sound, both relevant and non-relevant.1,3

The results of the study further indicate that the brain can selectively suppress external information during dreams, keeping people immersed in whatever world the mind has conjured up. While dreaming may seem like a funny byproduct of shutting off our brain for eight hours, recent research has hypothesized that dreaming is actually important for physical and emotional health.2 Therefore, the brain’s ability to prevent external sounds from interfering in the dream world may be important for health and wellbeing.

What is next in the study of dreams? Although dreaming is most common during REM sleep, dreams can occasionally appear in other parts of the sleep cycle. As such, further research must be done to determine if the brain also protects the dreaming state outside of REM sleep or if there is another (or any) mechanism in place.

Bibliography

[1] CNRS. (2020, May 15). The dreaming brain tunes out the outside world. ScienceDaily. Retrieved May 17, 2020 from www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2020/05/200515131915.htm

[2] Leonard, J. (2017, September). REM sleep: Definition, functions, the effects of alcohol, and disorders. Retrieved from https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/247927

[3] Matthieu Koroma, Célia Lacaux, Thomas Andrillon, Guillaume Legendre, Damien Léger, Sid Kouider. (2020). Sleepers Selectively Suppress Informative Inputs during Rapid Eye Movements. Current Biology, 30, 1-7; DOI: 10.1016/j.cub.2020.04.047

Leave a Reply