Based on a recent study of twins led by Stanford University immunologist Mark Davis, the environment may play a larger role than genetics in shaping an individual’s immune system (1).

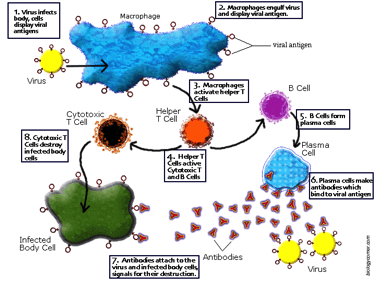

The immune system works to destroy pathogens and ensure future immunity through an intricate cascade of biological reactions. Each reaction involves a separate class of white blood cell that possesses a unique function (4).

The immune system primarily fights foreign agents such as bacteria or viruses that enter the body. These agents, also known as pathogens, possess surface proteins that stimulate white blood cells, particularly the B-lymphocytes and the T-lymphocytes, to mount specific responses. T-lymphocytes are directly responsible for the destruction of the pathogen. B-lymphocytes produce antibodies that will recognize the pathogen if it invades the body again. Hence, the immune system will work much faster during subsequent infections. This entire process is mediated by the ability of the immune system to differentiate between “self” and “non-self”, or native and foreign, particles (2).

Each person possesses a unique immune system. To see if this difference stems from genetic or environmental variation, Davis retrieved blood samples from 210 fraternal and identical twins ranging from 8 to 82 years old. He hypothesized that if genetics played the largest role, then identical twins sharing nearly the same genome should exhibit very similar immune systems (1).

His results proved the contrary. Based on over 200 parameters, including 51 types of immune cells and other implicated proteins, the differences in the immune systems of identical twins could not be explained by the slight genetic variation between them. Specifically, in about three-fourths of the parameters, the environment seemed to play the biggest role. The scientists also concluded that older twins had more divergent immune systems, likely because of the distinct environments each twin experienced as he/she grew up (1).

Davis and his team also studied how twins responded to flu vaccines. By checking for the number of antibodies produced, Davis concluded that the responses were not identical. Differences were attributed to unique flu strains experienced by each twin (1).

Additionally, the researchers studied pairs of twins in which one carried Cytomegalovirus (CMV) and the other did not. Cytomegalovirus goes largely unnoticed in healthy people and only leads to symptoms in those with compromised immune systems. CMV accounted for differences in nearly 60 percent of the parameters in twins; those with CMV typically had a more hyperactive immune response (3).

Megan Cooper, a pediatric immunologist and rheumatologist, notes that this study may explain the dilemma of autoimmune diseases. People with close relatives affected by autoimmune disease are genetically susceptible, but whether or not they actually become affected may be a factor of environmental exposure (3).

The information from this study may prove particularly useful for those who may be genetically at risk for an immune system disorder. These people may be able to manipulate their environment to reduce the likelihood of developing disease. The results may also be used to promote healthy practices among the general population for greater immunity against common infections.

Sources:

1. Conover, E. (2015, January 15). Environment, more than genetics, shapes immune system. Retrieved January 17, 2015, from http://news.sciencemag.org/biology/2015/01/environment-more-genetics-shapes-immune-system

2. Durani, Y. (Ed.). (2013, January 1). Immune System. Retrieved from http://kidshealth.org/parent/general/body_basics/immune.html

3. Neergaard, L. (2015, January 17). Study: Environment trumps genetics in shaping immune system. Retrieved January 17, 2015, from http://www.sfgate.com/news/medical/article/Study-Environment-trumps-genetics-in-shaping-6018208.php

4. Acquired Immune Response. (n.d.). Retrieved January 18, 2014, from https://bcscience8.wikispaces.com/Acquired Immune Response

Leave a Reply