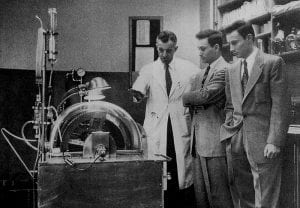

Richard Herrick (middle) and his brother Ronald (right) were the first to undergo a successful kidney transplant with Ronald donating a kidney to his brother. Here, Dr. John Merrill (left) shows them an artificial kidney. (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

On September 25, Abigail Marsh, Assistant Professor of Psychology at Georgetown University, gave a lecture on the neurological bases of “empathy on a sliding scale,” which ranges from psychopathy to extraordinary altruism. Despite many common misconceptions, Marsh explained that psychopaths are not serial killers, psychotic, or sociopathic, a term not often used by psychological researchers (A. Marsh, personal communication, September 25, 2015). Psychopaths are defined by four main traits of being callous, remorseless, loveless, and, according to Marsh, most importantly, fearless. Despite these specific emotional deficits, psychopaths can be skilled at social interaction.

Marsh emphasized that psychopathic individuals are not emotionless. Rather, they lack fear, have reduced fear-related physiological responses, such as skin conductance, and are less responsive to aversive conditioning, in which painful stimuli are associated with unwanted behaviors. Furthermore, many psychopaths are continually in and out of prison, which suggests that imprisonment has no effect on curbing psychopathic behaviors.

Additionally, Marsh noted that psychopathy is a developmental disorder and a number of studies of children have predicted psychopathic behaviors later in life. For example, lowered skin conductance responses of two-year-olds and babies’ reactions to a noisy robot are associated with psychopathy.

Researchers have struggled to obtain a reliable group of psychopathic individuals. Recruiting psychopathic individuals from prisons results in confounding psychopathy with neurological changes induced by imprisonment. Thus, many studies focus on children and adolescents. When asked to describe a time when they felt fear or anger strongly, the only difference between individuals with psychopathy and the control subjects was their attitude towards fear. Psychopathic individuals had difficulty recognizing fear in faces, posture, and voices and demonstrated a deficit in experiencing fear.

These results suggest that dysfunction in the amygdala, the fear center of the brain, could be a root cause of psychopathy. Indeed, psychopaths have reduced amygdala volume and, even among individuals with varying levels of psychopathy, amygdala volume is negatively correlated with psychopathy.

Just as researchers now believe psychopathy is a continuous, rather than discrete, condition, Marsha and her colleagues believe that on the opposite end of the “continuum of caring” could be extraordinary altruists, the “anti-psychopaths.” Marsh has focused on altruistic kidney donors, individuals who have donated a kidney to complete strangers. Kidney donation involves a painful recovery period, a one in 400 chance of fatality, and no monetary compensation under U.S. law. When Marsh and her team interviewed these individuals regarding their motivations for donating a kidney, many of the responses boiled down to the fact that many people are suffering. Furthermore, many of these individuals appeared not to understand why others were not doing the same. When Marsh and colleagues repeated the study investigating amygdala size, they found increased amygdala activation in response to fear but not anger, as well as increased fear recognition, but decreased anger sensitivity compared to controls. This supports the characterization of extraordinary altruists as the empathetic inverse of psychopaths.

So why is fear, rather than pain or anger, associated with empathy? Marsh hypothesizes that the facial expression for fear appears more vulnerable and infantile, increasing an observer’s affiliative response to the individual expressing fear. Some studies have shown that people pull a lever toward themselves more quickly in a categorization task of fearful facial expressions. Because of the infantile features of the fear facial expression (wide eyes and high eyebrows), Marsh believes the fear expression may activate a caregiving response and, thus, urge people to approach the fearful individual (1).

References:

1. Marsh, A. A., Kozak, M. N., & Ambady, N. (2007). Accurate Identification of Fear Facial Expressions Predicts Prosocial Behavior. Emotion (Washington, D.C.), 7(2), 239–251. http://doi.org/10.1037/1528-3542.7.2.239