Anahita Kodali, Medical Sciences, News, Spring 2020

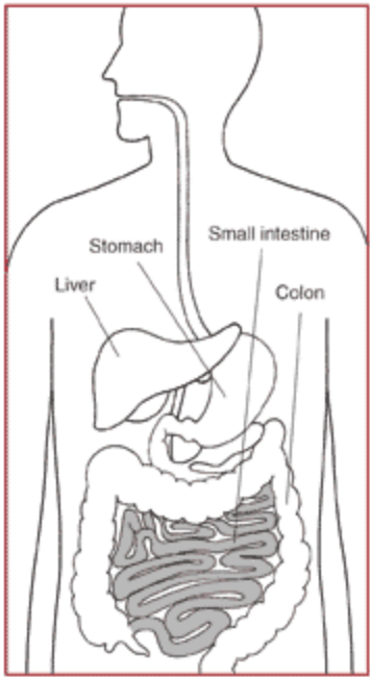

Figure 1: There is more to the digestive system than the small intestine; this diagram shows four of the largest structures in the body’s digestive tract, though there are yet other organs that help the body process food into energy.

Source: Wikimedia Commons

We’ve all experienced “gut instincts.” Perhaps you’ve decided against taking a class for no reason other than thatfeeling in your gut; maybe you were on your way out when you suddenly on a whim decided to stay in instead. These innate feelings have been studied by biologists and neuroscientists for several years. There is already conclusive evidence that the portions of the brain controlling basic and automatic biological functions are very responsive to different signals sent by the gut. When we ingest food, for example, the gut sends signals to the brain to induce digestion automatically. 1However, researchers have recently become interested in studying whether the gut can also influence the brain’s higher functions, including those that control emotions.

To investigate the small intestine’s impact on the brain, researchers in the Neuroscience Program at University of Illinois inserted viruses modified to be attracted to neurons into the small intestines of several rats. By tracking the progress of these viruses along spinal nerves and in different parts of the brain, the researchers were able to emulate the normal neural signaling pathways between the small intestine and brain. Unsurprisingly, the researchers found that the viruses would travel to the lower portions of the brain, which have already been proven to be connected to the gut. However, Colton Parker, a doctoral student on the research team, commented that “things got more interesting” as the viruses surpassed the lower portions of the brain and entered portions that are reserved for higher emotional processes and for cognitive function. 2

In addition to linking the gut to the higher brain, the researchers were able to better understand the mechanisms that the gut actually uses to communicate with the brain. Prior to this study, scientists had assumed that there were two distinct sets of neurons used in sending sensory information to and from the brain. The first –sensory neurons – took sensations from different parts of the body to the brain. The second – motor neurons – sent the brain’s response back to the part of the body where the sensation originated. However, by studying the map of neural pathways created by the virus, the researchers determined that at least half of the neurons actually transmitted both types of signals. 2

Overall, the study’s findings have several significant impacts. Scientists now have a much better understanding of the body’s neural architecture and the way that the body and brain interact to send and receive signals, helping us better understand how neurons function. In addition, the findings regarding the gut’s contact with the emotional processing centers in the brain opens the door to much more research regarding human’s emotional responses to food. Why do some of us get “hangry”? Why do many depressed patients also experience digestive issues? Why do many of us continue to eat even when we feel full2? The answers to these questions, and many more, may soon be answered.

Bibliography

[1] University of Illinois College of Agricultural, Consumer and Environmental Sciences. (2020, April 2). Gut communicates with the entire brain through cross-talking neurons. ScienceDaily. Retrieved April 7, 2020 from www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2020/04/200402155733.htm

[2] Coltan G. Parker, Megan J. Dailey, Heidi Phillips, Elizabeth A. Davis. Central sensory-motor crosstalk in the neural gut-brain axis. Autonomic Neuroscience, 2020; 225: 102656 DOI: 10.1016/j.autneu.2020.102656

Leave a Reply